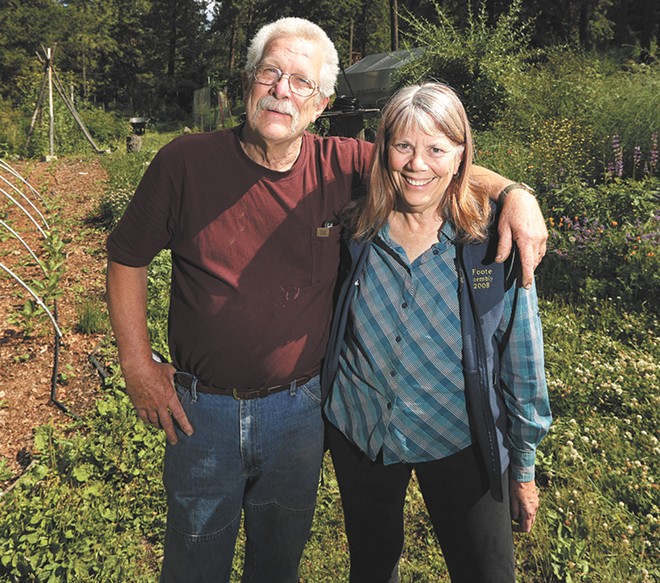

Torie and Thom Foote have always grown their own food, first in Alaska, where they lived for 30 years, and more recently in Colbert, where they relocated in 2011.

Nestled in a clearing on a forested slope north of Spokane's urban edge, the couple's Footehills Farm produces an assortment of fruit and vegetables, lots of garlic and more than two dozen herbs for both culinary and medicinal applications.

Although the Footes have been gardening all their lives, they more recently learned firsthand the importance of soil, especially when they decided to go from growing their own food to creating a sustainable, income-producing farm.

"How good a plant looks is merely a reflection of how good the soil is," says Thom, paraphrasing a friend's advice.

And soil health, or what farmers call tilth, is essential — so much so that the Footes have gone to great lengths to not only improve their soil, but to grow it themselves. Yes, that's right; the Foote's grow their own soil.

First, some background. Soil is essentially the surface of the earth, but also everything that comprises it: organic matter (around 5 percent), water and air (about 25 percent each) and minerals (45 percent), according to Natural Resources Conservation Service data. The Footes' 10-acre property, although full of trees and vegetation, consists of silty clay loam, typical of Eastern Washington areas where Ice Age glaciers retreated. They needed to rethink their approach.

Surely they could (at great expense) have dirt or soil amendments, like organic matter, hauled up to the hillside, but without a method for containing the dirt and maintaining the soil health, the solution wasn't sustainable or economical. Instead, Thom signed up for a permaculture design class in 2012 taught by Michael "Skeeter" Pilarski, a recognized expert in permaculture.

What is permaculture? Pilarski defines it as the interdisciplinary design of "sustainable human settlement," synthesizing "agriculture, ecology and forestry."

Local permaculture, composting and biodynamics instructor Ryan Herring puts it another way: "It is a design tool used to regenerate soil, water, food, health and other resources that also creates resiliency in all of them at the same time."

Many people are already applying permaculture techniques without even realizing it, says Herring, such as eliminating chemical pesticides and fertilizers, using heirloom seeds, companion planting and maximizing watering. The Footes do all this and more, like using a solar-powered drip irrigation system Thom designed after earning a nearly $5,000 grant from the HumanLinks Foundation, a nonprofit that supports sustainable farms in Washington state.

Permaculture also includes composting, which the Environmental Protection Agency describes as a balance of "brown" organic matter, such as dead leaves or straw, and "greens," such as grass clippings, non-meat food scraps and even coffee grounds, which, when combined in ideal conditions, decompose to help build more organic matter.

However, says Thom, permaculture is not limited to a single technique, which can vary according to growing situation. "Permaculture is, at its core, a design tool," he says.

When they compost, the Footes use local coffee grounds and leaves because, says Thom, "one of the goals of permaculture is to reduce external inputs," wherever they may be on the food chain.

The Footes have gone a step further than composting by creating a sustainable food source of organic material beneath their plants. The process, called hugelkultur or hugel, translates to "hill culture" and involves mounding soil on top of materials that will decompose — newspaper, leaves, branches and even logs — providing plant food, retaining moisture and even raising the temperature of the soil as they do so.

Hugel beds, for example, allow the Footes to extend their growing season, reduce watering and even winter over herbs, like rosemary, that would otherwise perish.

Another project involves using biochar, which can be made by turning animal waste into a form of charcoal (the Footes are saving up for a composting toilet), in the growth of their basil for a Washington State University-led experiment. They're also testing the basil for its sugar content (using a method called Brix testing, usually applied to fruit) whereby higher sugar content equates to better flavor, but also better soil health and improved pest resistance in the leaves of the plant.

Some of what's grown at Footehills Farm is for the couple's own consumption: peaches, strawberries, raspberries and rosehip bushes they're turning into a "living" fence, along with produce like asparagus, peppers, tomatoes and herbs for cooking, drinking and making Torie's medicinal ointments. Yet much of what the couple produces, they trade — lemon balm to Hierophant Meadery, Thai basil to Maw Phin Thai in Mead — or sell through their website and via LINC Foods' cooperative.

Other clients include Central Food, the Davenport hotels, Perry Street Brewing, Ruins and Gonzaga University's food services provider, Sodexo. Cochinito Taqueria uses some of Footehills' more unusual herbs, including papalo, a cilantro-substitute, and epazote, which helps de-gas beans. Herb crops also include basil, chervil, chamomile, dill, marjoram, mint (peppermint, spearmint, chocolate mint), oregano (both Mexican and Greek), parsley, sage, savory and thyme.

Fleur de Sel's Laurent Zirotti uses the Footes' chocolate mint, rosemary and lemon thyme, which he infuses into creme brûlée.

"Supporting local farmers is our duty and privilege," says Zirotti, "but the produce you get from a few miles away will always stay fresh and vibrant [longer] than the ones you get from hundreds of miles away."

The Footes get a lot out of their nearly one-acre growing space, which is designed to fit with their land's dense vegetation. Elsewhere on the property is a tiny house for guest workers from workaway.org and Worldwide Opportunities for Organic Farms, a pen for hogs, another for both meat and egg chickens, and turkeys. An easy-up-style tent is strung with drying herbs, while two cats, Pesto and Moose, and an ebullient black lab mix named Chena have their run of the place.

The Footes make their farm available to interested groups and are involved in teaching permaculture — both have extensive teaching careers behind them, especially Torie, who taught at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. Torie, who is concerned about local farmers being pushed out, also serves on the Spokane Food Policy Council, while Thom is involved in the Tilth Alliance's upcoming Spokane conference (Nov. 9-11).

Permaculture, say the Footes, is about more than just planting. It's a mindset about one's relationship to the land and to others. And on their land and in their life, they follow three corresponding principles: "care of the land, care of the people, sharing of surplus." ♦

More on Footehills Farm at footehillsfarm.net and on Instagram @footehillsfarm