Heather Audel-Neal remembers a specific moment from last March pretty well. She was sitting in a doctor’s office with her husband, awaiting the results from a fresh round of exams: blood tests, an MRI, a spinal tap.

She was tired, like most days. Her head wobbled, a tremor she had learned to accept. Her mind wasn’t as clear as it had been more than four years before, when she had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, but she was sure of one thing — this new Spokane doctor wasn’t going to tell her anything she hadn’t heard before.

After all, she’d been to three different neurologists and they had all agreed. She had MS. She had scoured the Internet for clues to her life-altering condition, looking for ways to cope with it, to pretend nothing was wrong with her.

But Dr. Michael Olek, a neurologist who had joined Rockwood Clinic just a few months before, surprised her. He said something she wasn’t quite prepared for.

“Dr. Olek came back after all these tests and said, ‘You don’t have multiple sclerosis,’” Audel-Neal says. “I said, ‘Would you have ever called this MS?’ He said no. I said, ‘Well, was my case just really tricky?’ He said no. I said, ‘What do I do now?’ He said, ‘Go off all these meds.’”

Four years after the fact, Audel-Neal was told she had a brain stem stroke. It was a result of Hughes Syndrome, or antiphospholipid syndrome, a disorder that causes increased clotting of the blood.

“My husband’s in tears and angry, and I’m just sitting there trying to make it all fit,” she says.

Turns out, it’s not as hard to fit as she thinks. Olek, a renowned neurologist who specializes in MS, says Spokane’s reputation for having the world’s second-highest incidence of the condition is nothing but a myth.

“I don’t believe we have a high incidence here. I mean, no higher than anywhere else in the country,” Olek says. “I don’t think we have an epidemic here. The numbers show a high incidence. But maybe the numbers aren’t correct.”

According to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, self-reported client data from the Greater Spokane area suggests the Inland Northwest is behind only the Shetland Islands (off the coast of Scotland) for MS rates.

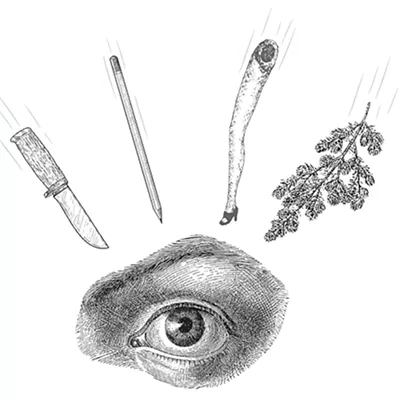

An estimated 400,000 people have multiple sclerosis in the United States, and the condition most commonly strikes white women between the ages of 20 and 40. The condition causes the immune system to attack the central nervous system and leads to lesions on the brain. Symptoms, which can come and go without explanation, include blurry vision, slurred speech, tremors and extreme fatigue. Paralysis and blindness can occur. The staggering diversity of neurological symptoms can lead to difficulty in diagnosing the condition.

“Twenty years ago, they didn’t have any way to diagnose it. It was the opinion of a doctor,” says Kerry Wiltzius, program director for the local chapter of NMSS. “They could guesstimate. It’s a puzzle with a lot pieces. They’re trying to get all the pieces together.”

Wiltzius says there are many factors that could lead to an MS diagnosis, including genetic risk. But perhaps the most important factor is where a person lives. The further from the equator, the higher chance someone has of being diagnosed with the condition. Decreased exposure to sunlight, which leads to a decrease in Vitamin D production, has been linked to MS.

“Not only are they finding it, but they’re finding it more,” Wiltzius adds.

In Spokane, perhaps too much more. In his year at Rockwood, Olek says he’s seen about 500 MS patients. Of those, he estimates he’s re-diagnosed 20 to 30 percent as not having the condition.

“They come to me usually for a second opinion. I’ll do things that haven’t been done,” he says, noting that he reviews a patient’s history and performs a physical, an MRI, a spinal tap and a sensory reaction exam called the “evoked potential.”

“I don’t want to give false hope,” he says. “But with almost any serious disease, it’s good to get a second opinion.”

For Audel-Neal, it was a fourth opinion. Switching gears from MS patient to stroke victim was a bit jarring, but she says she feels like herself again. She quit taking Copaxone, a popular MS drug that she used to inject into different parts of her body.

“Four or five weeks after not having the shots, I wasn’t tremoring as much. A couple of more weeks, I went, ‘I feel good.’ I hadn’t felt good in four and a half years,” she says.

She’s gained some weight back. Her 17-year-old daughter says she didn’t realize how bad her mother was until she got so good. Audel-Neal wants to go back to work, back to her career as an art instructor. She still gets a little head tremor every now and then, but it’s nothing compared to how she was even a year ago. And now, instead of the daily needles, all she needs is a baby aspirin every morning.