Smart home technology is poised to change how we run our lives — from garage doors that you control with your phone from anywhere in the world, to a refrigerator that allows you to peek inside while you're at the store, to lights that respond to every whim, even offering an artificial sunrise to ease you into your day. But what's somewhat surprising is that the actual construction of housing hasn't changed too much over the past 20 or 30 years.

That doesn't mean progress hasn't been made in building homes that are pleasant to inhabit and kind to the planet. It just means we've been slow to adapt.

"I have a problem with that," says Spokane architect Sam Rodell. "It mystifies me why the architectural community isn't all over this in this community. It is something that has been much more widely adopted on the West Coast."

The "this" he's referring to is something called the passive house. It's not a great name — the meaning doesn't accurately translate from the German origin, and it tends to sound, well, boring and stodgy. In reality, passive homes are anything but.

What, no furnace?

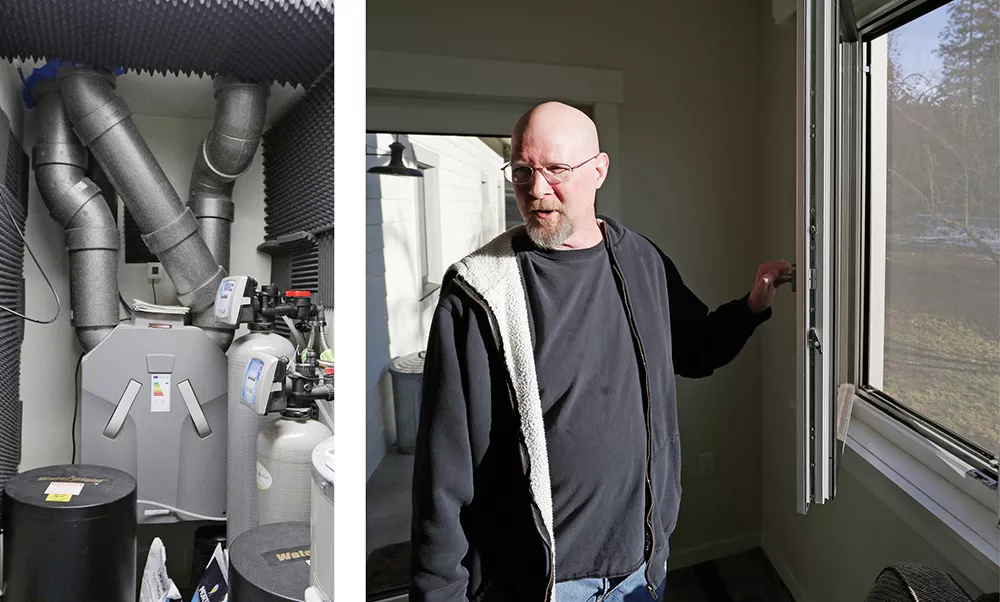

Mark and Allison Gessner decided to move north — leaving the Dallas area with their two school-age sons. They wanted some land and a place for the kids to run around — space to spread out, with a creek for the boys to enjoy. And they wanted to build a passive house. Allison says her father mentioned the idea to them, and after some internet searching they found Rodell, who, along with Maren Longhurst in his office, is one of two Certified Passive House Consultant architects in the area. Rodell's office wall is lined with certificates from numerous homes he's designed that meet the exacting energy-efficiency specifications established by the Passive House Institute of the United States.

Locating the right piece of property took some scouting, but the Gessners settled on land on the western edge of Idaho, near the state line.

After a year of living in their farmhouse-style passive house, they are still settling in.

"I really like it," says Mark on a cold but sunny afternoon, sitting in the home's cozy great room. "It's kind of like we're cheating. It's a little bit weird, and I'm still not used to it. I grew up in Pittsburgh, which is similar weather to this, maybe a little bit less snow, but in wintertime when it was cold, you would stand by a window and even if you couldn't see outside, you knew it was cold out there. Here you really can't tell."

The indoor temperature holds steady at the thermostat setting — the Gessner's prefer a pleasant 72 degrees — despite that fact that passive houses don't have furnaces.

The passive house is purely based on physics. It's kind of the Tesla of architecture."

That's right. No furnace. "We had neighbors who came to greet us when we first moved in," recalls Mark, "And they said, 'Where's your fireplace?' I said, 'We don't have a fireplace. We don't have a furnace, either.' They're like, 'Are you nuts? You're going to freeze!'" Allison laughs, "Those dumb Texans!"

How is it possible? A passive house starts with crafting a virtually airtight exterior or "envelope." For the Gessners, that meant coating the plywood on the entire exterior of their home in a green sealant, which was then overlaid with sheets of styrofoam. The home was built on a concrete slab, which was laid over an 8-inch styrofoam layer. The windows are all triple-pane, imported from Germany.

Those are just some of the various building techniques that can be used to create a passive house. Gavin Tenold, a Certified Passive House Consultant and Certified Passive House Builder at Copeland Architecture in Spokane who built the Gessner's home, says rather than a "prescriptive" code that specifies, for example, how many BTUs are required in a house, passive houses are evaluated based on performance — through "running energy calculations and making sure the building will perform to what is required for passive house standards."

Every detail of the finished home has to be planned, with its effect on air energy loss and gain calculated. "The passive house is purely based on physics. It's kind of the Tesla of architecture. There's no intuition involved, it's science," Rodell says.

"You cannot have anything going through the wall," Mark Gessner says. "So if you want to have cable TV, they can't just come in like they normally do and drill a hole through [the outside of the house]."

All that careful attention to the design and planning yields a pretty airtight structure. But passive homes have to pass another test. At some point in the construction, when a visual inspection seems to indicate the house is sealed up, the actual air-tightness is assessed using a blower at the front door to suck air out of the house and evaluate how much outside air leaks in.

On the Gessner home's first air blower test, the technician told the owners that the total area of all the holes in the envelope of the house was about equal to the size of a playing card. "And that was too big for a passive house," Mark says. "It had to be half that size. It's an intense process."

While Washington's building codes are some of the most rigorous in the United States in terms of energy efficiency, they are still a long way from passive house standards. But that's changing. "You're seeing a lot of this coming from commercial codes that are pushing the trades a little bit further," Tenold notes. "I've been doing this since 2011. Insulation contractors, when I first started, the idea of putting insulation on the outside of a wall was foreign. They hadn't seen that yet. It was very hard to source triple-pane windows. It is now much easier. I think that in the next 15 years this is going to become, if not code, it is going to be common."

Benefits of passive house

Why bother with such an airtight envelope? It's all in the numbers. Basically, the less energy that escapes from the house in the form of conditioned air, the less energy it will take to keep it at a pleasant temperature. Think of the passive house as a Thermos of sorts. And even without a furnace, lots of heat is generated in a house.

"The interior environment is very warm," Tenold says. "We have televisions, we have refrigerators, we have lights, we have hot water lines going to our faucets, we cook — all of these are places where heat is captured." Even body heat from residents and pets adds up.

While conserving all that heat energy can be a good thing when it is cold outside, an airtight house would quickly become stale and damp, and generally unpleasant — think of sitting in a car with all the windows up. That's one of the common misconceptions Rodell says he addresses for clients considering a passive home. In reality, passive homes have exceptionally clean, fresh indoor air.

The heart, or perhaps more accurately, the lungs, of passive homes are called heat recovery ventilation systems — or HRVs. "We cycle the same amount of air simultaneously in and out of the building and it passes by the energy recovery overlap," Rodell says. The process transfers warmth from the outgoing air to the incoming air and filters it, providing a steady supply of clean, temperate air, all at more than 90 percent efficiency. It can also work in reverse to cool incoming air if it is hot outside. Heat pumps provide supplemental heating and cooling when needed. Passive homes generally use 60-70 percent less energy than a conventional home. "It's just kind of this win-win situation, where you are saving money, you are living in a higher quality environment, and more of your money is going into your equity than into your power bills," Rodell says.

Everyone associated with passive homes talks about the purity of the indoor air supply. "We usually have really good indoor air even when there's smoke," Mark notes. The MERV 13 filters in the Gessner's home are just one step below hospital grade. Even when outdoor air quality is compromised, "The interiors of these buildings are pristine," Rodell says. Tenold points to a 2015 Harvard study showing office workers had significantly improved performance on a variety of cognitive tests in air mimicking a "green" office versus air mimicking "conventional" office conditions.

Accommodations when going passive

So does your airtight home have to be a grim, utilitarian place constructed solely for its energy efficiency? In a word, no. "These are bright houses with beautiful windows," Tenold says. Windows that can open, Rodell notes, dispelling another myth about passive homes. "There's no relationship between architectural character and high performance construction. In our office, we want to lead with the architecture. We want to do strong architecture that works for the client and the land. And then we just apply the technology."

"Windows on the south side are good. With overhangs you can get winter sun and keep summer sun out."

Most clients actually don't come in looking to build a passive house, Rodell says. Instead, he starts by developing a design, and then he shows clients case studies of what the cost of ownership of the house will be if it is built to code, and if it is built to passive house standards. "It's an informed choice that they make," he says. When shown the numbers, most end up opting for the passive house standards, which generally add just 5-10 percent to the cost of the home.

Rodell recently designed a passive house for a retired couple, built on an infill lot previously deemed unbuildable because it was a giant chunk of basalt. (Pictured on pages 24-26.) "The architecture became very much an extension of the site," Rodell says. "We built up the stone walls out of the basalt."

The plan features a central courtyard and windows abound in the airy, open interior. Rodell says a common misconception is that windows are limited in a passive house. Window placement does require planning during the design phase, but there are many options. "Windows on the south side are good. With overhangs you can get winter sun and keep summer sun out." Western sun is a little harder to manage because it is lower in the sky. So the South Hill home's driveway is on the west side, leaving an abundance of glass facing east, south and north.

The warm, yet contemporary home's interior doesn't readily give up the secrets of its passive design. And the exterior cleverly conceals an array of solar panels on the roof. Rodell says the homeowners were initially reluctant to add solar panels for fear they would detract from the home's appearance and be unpopular with neighbors. Through computer aided design, the homeowners got to see exactly how the house would look from every angle when it was built and gained confidence to add a solar panel array to an obscured area on the roof, certain in the knowledge that the panels would not be visible to them or any of the neighbors.

The Gessners say they made just a few small accommodations related to the passive house design. "We got an induction cooktop," Allison says. "It wasn't a requirement, but it doesn't release as much heat (as a gas range) into the house." And then there was the issue of the clothes dryer. A standard dryer is not an option in a passive house because it pulls conditioned air from the interior and exhausts it outdoors. So the best option was a heat-pump dryer, "which is something I guess they use in Europe where they have old houses that didn't have dryer vents put in," Mark says. "It basically has a closed cycle — the water that it evaporates passes over a condenser and then is pumped down the drain. When I first heard about it, I said 'No thanks. It's going to be just terrible.' But I really, really like it. I was really surprised. That was probably the biggest surprise I've had in this house."

The big picture

So where does passive construction go from here? Rodell points to the economic good sense of passive homes, but notes that while building residences to passive house standards is undeniably good for our carbon footprint, the real savings may come from commercial buildings adopting the methods.

Sunshine Health Facilities CEO Nathan Dikes has already commissioned Rodell to design two such buildings at his company's expanding campus in Spokane Valley — a three-story assisted-living residence and an annex to an existing building to house the company's headquarters. For the three-story residential building, "We would have typically thought between $8,000 and $10,000 a month for utilities. It's between $500 and $1,000 a month, maybe $1,200. ... The air is cleaner, because it is constantly being filtered ... We love the fact that we can provide quality housing and health care to our residents here," he says. In the office annex, passive house technology allows air from the commercial kitchen and high-efficiency laundry areas to be filtered so that it doesn't mingle with the rest of the spaces, all while maintaining a pleasant ambient temperature for employees in those areas, as well as the office zones. Despite the somewhat lengthier design and construction process as compared to conventional building, Dikes says the passive house technology has been a worthwhile investment. "In health care, 70 percent of our expenses are labor, you have be very mindful of all costs. It took extra money to invest in order to reap the rewards... Would I do it again? I would do it again in a heartbeat. I will only build a passive house how."

The building revolution is already well underway in Europe. Tenold recently returned from a trip with a Spokane delegation to Denmark and Sweden. "Every building that we went to was nearly net-zero, and the entire European Union is requiring nearly net-zero construction by the year 2020. That is soon, and they are on pace to make this," he says.

But there's more to it than simple economics for Tenold. "It's funny. In America we always try to quantify these things in terms of dollars and cents. I think when you look at it through a different lens, in terms of, why don't we just build the best quality building that we can build? Our health is going to benefit. We're going to perform better as human beings in it. I'm building a building that is going to last longer ... It's just a framework of quality and your enjoyment of the building."