Josh Randall, a lanky 20-year-old with brown hair and a wispy beard, is surrounded by dropouts. He’s sitting at a table in a noisy room at Crosswalk, a teen shelter in downtown Spokane that doubles as a school for kids pursuing their GEDs. In the background, teens dish up fried chicken for lunch, a round of applause breaks out, and someone’s baby cries, louder and louder, in a nearby crib.

Ask Randall why he dropped out and he’ll rattle off a list of reasons. The pace at Lewis and Clark High School was too fast and the workload too much. At home, he couldn’t focus. He couldn’t sleep. Teachers gave up on him. One said “he didn’t effing care about trying to help me,” Randall says.

But ask Randall when life really went downhill and he recalls the exact day. He says he came home to find the front door locked. The garage was open, and moving boxes were stacked on the front porch. Randall’s mother, he says, came home five hours later.

“She said she was moving. I asked, ‘Where are we going?’”

No, she was leaving, she told him. He wasn’t. She dropped him off at Crosswalk the next morning.

“Sorry, my head’s spinning,” Randall says, stopping his story.

His eyes look bleary. “Could we just wrap this up?” The other kids at Crosswalk tell similar stories. Their routes differed — pregnancy, drugs, fights, isolation, frustration with families, students and teachers — but the result was the same: They dropped out.

Indeed, only 65 percent of Spokane Public Schools’ class of 2009 graduated, and that’s counting those who took extra time to get their diplomas. More than 800 kids dropped out that year.

Spokane’s school district is in the basement when it comes to graduation rates, ranking 270th out of 282 districts in Washington. Its rate is 10 percentage points lower than Tacoma’s or Seattle’s and 17 points lower than Coeur d’Alene’s.

Lindsey Bristow, 20, at Crosswalk: "When I was 13, I ended up leaving home, got involved in the street and involved in methamphetamine." But on March 15, she'll celebrate a year clean. [Photo: Young Kwak]

The scope of the district’s dropout problem first hit Superintendent Nancy Stowell in the fall of 2008. She was working at her office computer, clicking through statewide schools data.

Before, Stowell had only looked at Spokane’s dropout numbers in isolation. But in that moment, she began to make a list of rates from comparable districts — Seattle, Tacoma, Yakima, Kent, Evergreen — as well as the rates of nearby districts like Mead, East Valley and Central Valley. Only then did she realize how bad things were.

“Honestly, when we compare ourselves to Tacoma, we far exceed what they were doing academically, but our graduation rate did not reflect that,” Stowell says.

The district had already been developing programs to stop students from dropping out, but in the last two years, she’s intensified those efforts. Even as they’ve cut the budget, they’ve invested in alternative programs to capture students leaving school.

The district isn’t alone in the fight. Last year, the dropout rate was the rallying cry for an initiative to fund youth programs. Also, Priority Spokane, an alliance of community leaders, identified graduation rates as the region’s most pressing mission and raised nearly $90,000 to study why students drop out and what resources the region has to stop them.

The stakes couldn’t be any higher, Priority Spokane member Mark Hurtubise says. A higher dropout rate means more people unemployed, more divorced, more in prison, and more in need of city services.

“If we don’t improve the graduation rate, if we don’t stop the dropout rate in this recession,” says Hurtubise, “communities will start to implode.”

RUNNING THE NUMBERS

On March 1, a FedEx delivery person handed researcher Mary Beth Celio a package containing a single high-density CD. On it were 158 data files containing every scrap of academic information on each Spokane student from the classes of 2008 and 2010.

Celio will spend the next six months in her home office in Seattle sorting that data, running it through algorithms and examining income, race, gender, discipline, test scores. She’s studied data for districts in Portland, Seattle, Renton, Kent, but the next half-year is all about Spokane.

Her mission: to discover which Spokane students drop out and why. Her research follows a 2009 study at Gonzaga University, funded by Priority Spokane. It came up with three suggestions for improving graduation rates: continuing to set high expectations, matching students with community resources, and developing an early warning system to identify likely dropouts.

“You can literally target the students, to find the students who need help, as early as the sixth grade,” says Celio, whose work Spokane Public Schools hopes to put into practice.

Matters of Accounting

Graduation rates are complicated. The most basic figure is the “ontime graduation rate.” That’s the difference between the students who were expected to graduate in 2009, for example, and the students who actually graduated in 2009. Extended graduation rates, meanwhile, include students who did graduate — it just took longer than four years.

But — and here’s the key — neither should include students who transferred to other schools or alternative programs. If a school can’t prove a student transferred to a new school, the state just assumes they dropped out. So at least part of the reason for Spokane’s awful graduation rate is, the district suspects, a problem of accounting. In the past, Spokane schools may have done a poorer job of tracking transfers than their counterparts.

So Spokane created a new position: graduation and college success supervisor. Joan Poirier compiles lists of students who left, and if the students transferred, helps the schools prove it. That alone, the district guesses, will increase their graduation rate by several points.

— DANIEL WALTERS

At Glover Middle School, Principal Travis Schulhauser is already working with a system of his own. He clicks open an Excel spreadsheet. On it is a list of every Glover student, along with a number, 0 to 3. The numbers represent three different warning signs: an attendance record of less than 80 percent, multiple disciplinary situations, or failure in math or English in the sixth or seventh grade.

If just one of those indicators is present, Schulhauser says, a student’s chances of dropping out jumps by 75 percent.

Last week, Schulhauser’s system was implemented at every middle school in Spokane.

The system has its dangers, though. If teachers aren’t careful, labeling a child a poor student can make them a poor student, says Fred Schrumpf, principal of Spokane’s alternative schools.

But for now, Schulhauser is using his system to find students in trouble and give them mentoring, after-school assistance or extra math help. Celio’s research is expected to hone the program, customizing it for Spokane’s struggles.

“The more information we have,” Schulhauser says, “the more we can troubleshoot.”

POVERTY, POTHEADS AND DISENGAGEMENT

One statistic has long stood as the biggest predictor of graduation: poverty. Principal Schrumpf says children in poverty often lack role models.

And when a family is living paycheck-to-paycheck, they aren’t thinking about college, he says. They’re thinking about survival.

In Spokane, low-income students make up most dropout cases:

Nearly two-thirds of the district’s dropouts came from families poor enough to qualify for free or reduced lunch. And over half of Spokane students qualify for free or reduced lunch.

“We don’t want to use poverty as an excuse, but it complicates the lives of our children,” District Superintendent Stowell says.

But family income doesn’t explain everything. Tacoma, for example, has a higher percentage of low-income students but a better graduation rate.

“If I only know the race and the income of the kid, I can only predict 8 to 12 percent of the dropouts,” Celio says. “If you have their grades, their absenteeism and their disciplinary actions, I can predict 60 to 70 percent.”

Ask kids at Crosswalk and other alternative schools why they started skipping and some will blame themselves. They made bad choices, they did drugs, they started fights, they ignored homework. A former North Central student says she made the wrong friends — “potheads” who preferred hanging out at McDonald’s or NorthTown Mall instead of at school.

Others will blame the school for not engaging them. One former Shadle Park student says that as a hands-on learner, the lectures “were so stinking monotone it made me want to throw up.”

Depressed and bored, former LC student Alyx Franz would skip class: "Nothing was about the content we are actually learning." [Photo: Young Kwak]

But also consider former Lewis and Clark student Alyx Franz. Her wardrobe — nose ring, psychedelic shirt, zebra-print tights — speaks to her unconventionality. She loves seeing live punk shows and psychedelic music, and she is now a member of an incredible number of youth organizations. But her junior year, depressed and uninspired by class, she would skip school, go down to the Spokane River with her sleeping bag and read poetry: Charles Bukowski, Anne Sexton, Jack Kerouac.

“I was soooo bored,” Franz says. “Nothing was about the content we were actually learning. It was about trying to please the college people who were giving out these standardized tests.” And since Franz didn’t think she’d go to college, what was the point?

“She’s almost in the gifted range,” Schrumpf says. “It’s a good example, I think, of how a student who’s put in the right learning environment is going to flourish. But put in a traditional learning environment, she’s going to fail. Or disengage. Or leave.”

Schrumpf says he thinks a third of dropouts are smart students who got behind or distracted for some reason.

Like, say, Spokane Mayor Mary Verner. “I had excellent grades,” Verner says. “I was tired of being in school.

You start to get bored with the content of your classroom. I didn’t feel challenged with my school work.” She got into a program similar to Spokane’s Running Start — taking college courses that would also fill high school requirements — but she ran into the same sort of boredom, and she dropped out to get a job as a receptionist. It would be 15 years before she got her diploma.

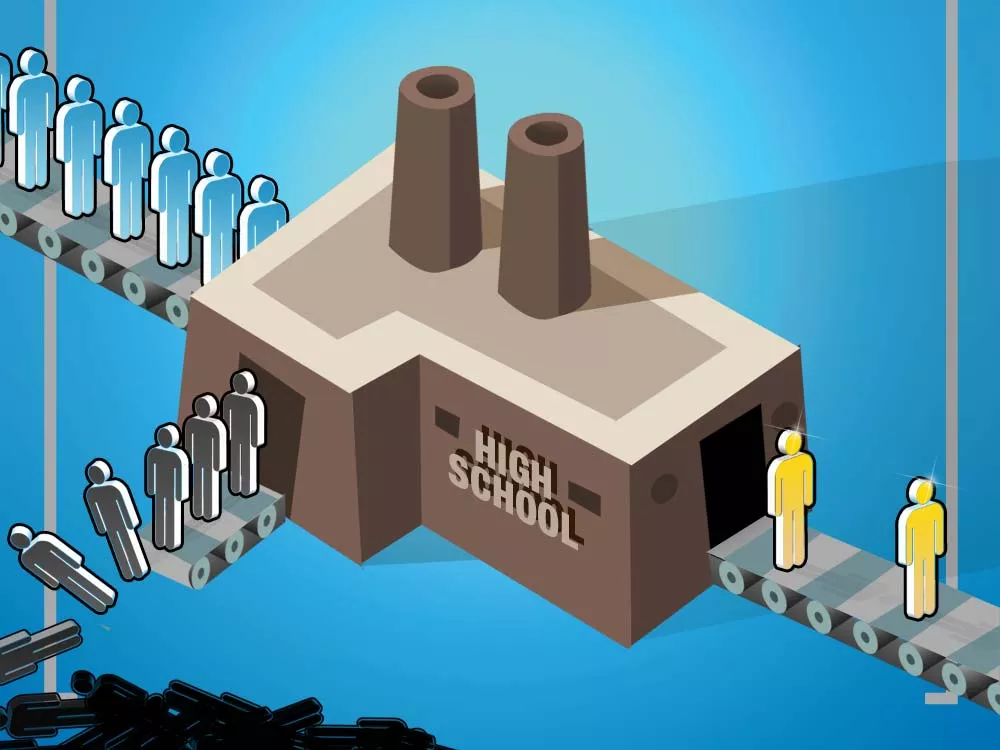

Being smart, in other words, doesn’t mean you won’t drop out. “Most people think people drop out from a single event in high school,” says Jay Smink, executive director of the National Dropout Prevention Center. Not true. “It’s really a series of disengagements by the students from a period that could start as early as kindergarten.”

Schools can cause those disengagements if they aren’t careful. “There are a lot of policies that push kids out of school,” says Smink. Holding a student back a grade. Homework policies that have no makeup option. Suspension.

“In Seattle, it was very clear after I looked at their data, any disciplinary action that resulted in even a single day of suspension was just a death knell,” says Celio, the researcher. Seattle responded by offering in-school suspension. “That simple thing has probably saved 100 kids already from dropping.”

COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS

It’s Friday at Cheney Middle School. For many students living in poverty across the country, the final bell for the weekend is bad news. Without free hot lunch, many students may not know when they’ll eat over the weekend. Not at Cheney.

One by one, 23 students go down to the office, grab backpacks from Communities In Schools on-site coordinator Sheri Frantilla, and hurriedly zip them open to see what’s inside this week: two mini-boxes of cereal, two juice boxes, a fruit cup, applesauce, a Nutri-Grain bar, a Chef Boyardee meal, a can of Beanie Weenies and — as a bonus — a Pop Tart.

It’s all thanks to Second Harvest Food Bank and the partnerships forged by Communities In Schools, a leading dropout prevention organi zation with chapters around the country.

Schools can’t do it alone, says Ben Stuckart, executive director of the Spokane County chapter, which has already placed on-site coordinators in several area schools.

“What happens in the school is connected to all our other systems,” Stuckart says. “For example, when the mental health system gets cut by the state, and we have more families and kids with mental illnesses who aren’t treated, they show up in the classroom, and the teacher is forced to deal with them.”

Ben Stuckart, executive director of the Spokane County chapter of Communities in Schools: "What happens in the schools is connected to all our other systems." [Photo: Young Kwak]

Stuckart touts studies calling the Communities In Schools model for dropout prevention the most effective in America. It’s a simple enough idea: Match students with community organizations that can help them — hungry kids with Second Harvest, for instance, or kids with bad teeth with dentists.

For 10 years, Stuckart says, another idea had been floating around, one that would hyper-charge dropout-prevention organizations with new funds, instead of just partnering with them. In January of 2009, Stuckart started to formulate a citizen’s initiative that would create a “children’s investment fund.”

The proposal asked Spokane voters to raise property taxes — costing the average homeowner about $69 a year — and create a $5 million pool to give grants to the sort of community programs that have been proven to increase graduation.

Portland did it. So did Miami and Seattle. Anecdotally, there have been successes, but no mind-blowing dropout reduction yet. Regardless, 65 percent of Spokane voters rejected the idea.

“If we had known the economy was still going to be in the doldrums — we shouldn’t have been on the general election ballot,” says Stuckart.

Without those extra funds to address dropout rates, Spokane Public Schools has had to get creative.

GETTING BACK “ON TRACK”

As Cody Rohrich speaks, he stares off into the distance. He mumbles a bit, beneath a cocked Mariners hat, remembering the moments that brought him here. The car wreck that he survived at age 6, but which left his mother dead. Later, the schoolyard fights he picked. The drinking

and pot smoking. The skipped classes. And the person at Colfax High School who said he might as well drop out, at the rate he was going.

But despite the grim prologue, Rohrich is still in the classroom. His hat’s off now, he’s on the computer, deep in algebra at the On Track Academy, one of three new alternative programs the district launched in the past two years to boost graduation.

“Now, not only am I going to graduate,” Rohrich says. “I’m going to graduate on time.”

The Mead Difference

Lincoln Road is the great divide: Students who live on one side of the street go to Rogers, with an on-time graduation rate of only 51 percent. Students from the other side attend Mead, with a graduation rate of 91 percent.

The Mead School District has an on-time graduation rate 37 percent higher than Spokane Public Schools.

There are clear differences.

Mead is smaller and wealthier. Spokane has nearly twice the percentage of students who qualify for free or reduced lunch that Mead has. And Mead, a district with more students in permanent houses, doesn’t nearly have the transfer rate that Spokane does.

But there are also differences in the way each district spends its money. Mead has sports all the way down to the fourth grade. Back in 2003, meanwhile, Spokane eliminated its grade school sports programs due to the budget. Only cross country — privately funded — remains.

— DANIEL WALTERS

When that person told him he was going to fail, Rohrich vowed to prove him wrong. He transferred to Shadle Park High School and there a counselor, seeing how far behind he was, suggested the On Track Academy.

“When I come here, I don’t consider it going to school,” Rohrich says. “I consider it seeing my second family.”

In a way, this school, occupying four cheap red portables near the Spokane Skills Center in Hillyard, is a lot like Crosswalk. The kids tell the same dramatic stories of how they lost their way, but there’s one big difference. These students haven’t dropped out — they’re on their way to getting their diplomas. In fact, 95 percent of the students at On Track graduated last year.

To be clear, only certain kids are chosen for On Track: kids with good standardized tests scores but awful grades or missing credits.

“What we found was that many students were incredibly bright,” says On Track administrator Lisa Mattson-Coleman. “But their transcript didn’t reflect that.” Something about school itself wasn’t working.

“The kids felt not heard, not seen, not known.

And then they give up,” Mattson-Coleman says. “Some of the sizes of our high schools — they’re like small towns.”

So the district created a new type of school. At On Track, most students only have one, maybe two teachers the entire day. Students work with their teachers to come up with their own customized plans — while still meeting state standards — and pursue their own assignments. Here, they complete missing credits. Perhaps most importantly, they have teachers who really know them.

“You can tell they actually care,” Rohrich says.

“I’ve never really had teachers do the things for me that teachers here will do. ... I got our rent money stolen — we couldn’t afford rent for a month. My teacher ... she pulled me aside and gave me the rent money.”

Surrounded by buzzing students, Karen MacDonald — “Mrs. Mac,” as some of the kids call her — plays chess against Alex Ramotowski, one of her students. He’s in trouble, with only a pawn and a castle defending his king against MacDonald’s considerably larger army.

“I know that by building those relationships with kids, and letting them know I respect them, I can get them to achieve more,” MacDonald says. The students open up, talking to her about their pasts. One student disclosed abuse she suffered and now, in counseling, she is writing about what happened and plans to share it with MacDonald. MacDonald promised the girl she would read it, but she’d have to do it at home. She knows it will make her cry.

“She’s like a mother,” says Kiona Dvorak, another student. She says she can talk to MacDonald about “my pregnancy, home life, schooling. … I couldn’t bring that up to any of my former teachers. They wouldn’t have the time, they wouldn’t want to hear it.”

Mattson-Coleman says that’s the key: At On- Track, a teacher spends so much time with so few students that she can’t help but get to know them, their life, their problems. “There’s a high degree of caring just by virtue of the system.”

So could this one-room-schoolhouse, projectbased model be successful at other high schools?

Mattson-Coleman brings her finger to her lips.

Shhh, she says, smiling. She thinks so. And at one of Spokane’s oldest high schools, it already is.

REINVENTING HAVERMALE

Large banners hang in the halls of Havermale High School, proudly listing every student who went on to graduate. For the average Spokanite, Havermale, nestled away off Northwest Boulevard near West Central, is the forgotten high school.

And for people who actually know of Havermale, it is often seen in a particular light.

“There was a perception that ... the ‘bad kids’ go there, that it was a school for tough kids,” lead administrator Cindy McMahon says. “They think that the kids fight here, that they do drugs.”

Maybe that was once true. But Havermale’s changed. There hasn’t been a fight all year. Havermale no longer exists as a six-period-a-day high school.

Scott Patton at Havermale, where students pick projects and work on them for three weeks. [Photo: Young Kwak]

“The fact is, and people don’t know this, the six-period day — do you know when that started? 1892,” McMahon says. Everything else since has changed. Why not that? “Kids don’t want to do the six-period high school experience. We want to offer a high school where students own their learning.”

Like On Track, Havermale’s Community School, a project-based alternative school, is a quiet education revolution. Here students may pick projects that interest them and work on them for three weeks.

“I finally did my first project,” says former Shadle student Sierra Potter. “It gives you an opportunity to focus on what you want to do after high school.” As an aspiring dental hygienist, she’s pursuing a project on dental hygiene.

Alyx Franz, the student who used to skip school to read poetry, is working on a project investigating what she calls “Spokane’s all-ages-venue massacre,” about the death of the Empyrean Coffeehouse and other similar local music venues. Like other Havermale students, Franz brags about the connection with teachers.

“They know your phone number,” Franz says. “They call you direct if you’re not at school.”

While the projects are the focus, students get breaks. Havermale offers students “wellness” courses, including sculpting, meditation, cooking and Zumba aerobics courses. They take seminars.

“We’ve only been in it four months,” McMahon says. It’s too early to know whether Havermale’s traditionally high dropout rates will be changed by the revamp, but there’s reason for hope. “The attendance has gone up 20 percent. The learning has gone up exponentially.”

Key to slowing the dropout rate, Superintendent Stowell has concluded, is offering options. Two years ago, On Track didn’t exist. Neither did Havermale’s project-based model.

Similar elements have spread to the traditional schools. The district has launched the ICAN program in every traditional high school to allow students to make up failed credits by taking abbreviated courses online. The Coeur d’Alene School District credits its online programs as the reason its graduation rate rose by 10 percent over seven years.

So, have all of these efforts actually improved graduation rates in Spokane?

Schools are still waiting to get the official numbers from last year, but the unofficial number of dropouts was 449 students, district spokeswoman Terren Roloff says. That’s 378 fewer than the year before. If the trend holds — and many hope it will — the strategies are starting to work.

CHANGING FUTURES

Back at Crosswalk, the students are working on a video project interviewing each other on why they dropped out. But nobody’s story ever ends with “… and then I dropped out,” because there’s another chapter after that: Nearly every student at the Crosswalk school is a few tests away from getting their GED.

Josh Randall pulls a folded-up piece of notebook paper out of his pocket. It’s a poem on his mixed feelings about love. He jokes that he’s a “master of the English language.” Then he shows how, by using the computer program GarageBand, he’s turned his poetry into music. He always loved poetry back in school.

“I like school work,” Randall says now. “I like learning.” Change is never simple, though. Cody Rohrich wasn’t at On Track last Thursday. He was in Colfax, dealing with the legal aftermath of a fight he got in last summer. But he’s confident in his future: He’ll get his high school diploma, then a community college diploma, then a four-year university diploma.

“I do want to have a family,” Rohrich says. “I already have 13 nieces and nephews. So probably only two kids, a boy and a girl.”

And how would he stop his kids from dropping out? “I’d probably bribe them to be honest,” Rohrich says, smiling.

Comments? Send them totheeditor@inlander.com.

*An original version of "Dropout Crisis" incorrectly alleged that, while the Mead High School had counselors, social workers, psychologists, Spokane Public Schools only had counselors. In actuality, many Spokane Public Schools have psychologists, mental health therapists and workers with social work degrees.