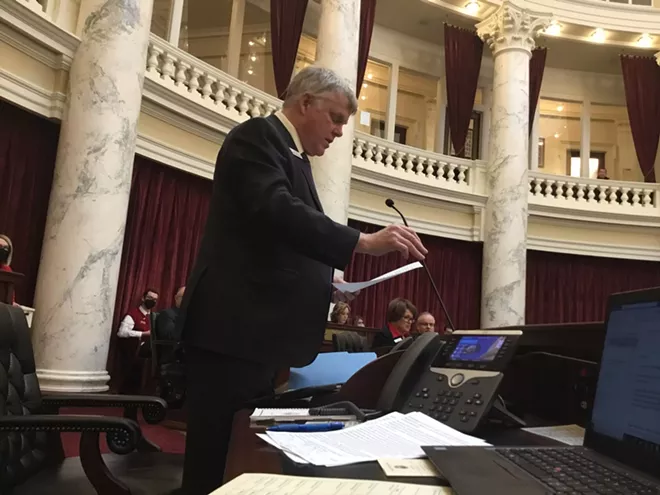

Infection was spreading in nearby Washington state. Sports tournaments had been canceled. Then-President Donald Trump had called for gatherings to be limited to only 10 people. But the Idaho Legislature continued to meet in person.

He’d had enough. He was going home.

“Good luck to all of you in this national crisis,” he concluded. The legislative session concluded just a few days later.

But when it came time for the 2021 legislative session, Idaho didn't go the route of Washington state, with most legislators videoconferencing from home.

And now, a year after Nelson delivered his speech warning about the possibility of the Idaho Legislature becoming a superspreader event, his fears appear to have been realized.

There's been an outbreak, one bad enough to shutter the Legislature for a few weeks.

"I’m sure there’s a big group in the Legislature that is refusing to test," he says.

On Friday, the Legislature voted to put the session on pause until April 6.

Among Republicans, he says, not wearing a mask almost became a badge of honor.

"The Republicans are appeasing their base who don’t believe in mask mandates, who almost don’t believe in COVID," Nelson says. "Wearing a mask has become a mark that you're a Democrat: 'Only Democrats wear masks.' It’s really hard to legislate if most of the body isn't wearing a mask."

Even after the outbreak, Idaho Speaker of the House Scott Bedke told reporters on a video conference today that while they would look at safety protocols when they return, they would "stop short" of mandating masks.

Nearly 2,000 Idahoans have died with COVID so far, though many did so in hospital beds and nursing home rooms, not in the streets. Idaho's in the top 20 states for the number of COVID cases per capita, though they're in the bottom dozen for COVID deaths.

Despite the in-person session, Nelson says he has remained healthy so far. The Legislature started offering COVID testing a few weeks into the session.

Nelson has received his first shot of the Moderna COVID vaccine, and he's a week away from receiving his second shot.

To be clear, the legislators who were infected weren't necessarily the most reckless members. After all, cloth and surgical masks are more effective at protecting nearby people than protecting the wearer.

Nelson says that Ruchti, the Democrat who got infected, was very diligent in wearing his mask, and that Republican Rep. Chaney wore masks more frequently than many of his Republican colleagues. Chaney made headlines last year for a Facebook video slamming the “snake oil salesmen and political opportunists” who he said were dishonestly using the backlash to COVID restrictions to sell their agenda.

In an interview with the Inlander last year, Chaney warned that if Idaho didn't take Idaho Gov. Brad Little's COVID recommendations seriously the state would pay the price and have to shut down again after it reopened.

"Look, you can believe, and maybe I'll agree with you that the government has no right to tell you that you're not allowed to drink bleach, but that doesn't make drinking bleach a good idea," Chaney said.

Yet Idaho also has a very angry group of anti-mask and anti-lockdown advocates. When state lawmakers limited seating in a special session last year to follow social distancing requirements, an angry mob of protesters broke the glass door of the Capitol and rushed in.

Ammon Bundy — a far-right Idaho resident famous for his 2016 occupation of the Malheur wildlife refuge — united a sweeping number of anti-vaxxers and anti-government activists under a "People's Rights" banner, adopting a tactic of protesting outside public officials' homes.

When Chaney introduced a bill to ban protests outside officials' homes, a mob showed up at his family's home, wielding actual torches, literal pitchforks and an effigy of Chaney.

Despite Idaho's considerable economic success during the pandemic, Nelson says that much of the legislative session has been over how to strip away much of Idaho Gov. Brad Little's emergency powers, constraining his ability to impose restrictions even during major disasters.

Even in a swing district like Nelson's, supporting COVID restrictions isn't necessarily an easy path to electoral victory.

In 2018, Nelson beat incumbent Rep. Dan Foreman by over 2,000 votes. But last year, facing the same opponent, he only squeaked by with a 220-vote margin.

"We had two debates and my opponent wouldn’t show up because he had to put his mask on," Nelson says.

So he figured out a compromise for rural areas: He would knock on the door with his mask on at first, introduce himself, and then ask if he could take his mask off so they could have a conversation with 10 feet of distance between them.

"This was a weird campaign," Nelson says.