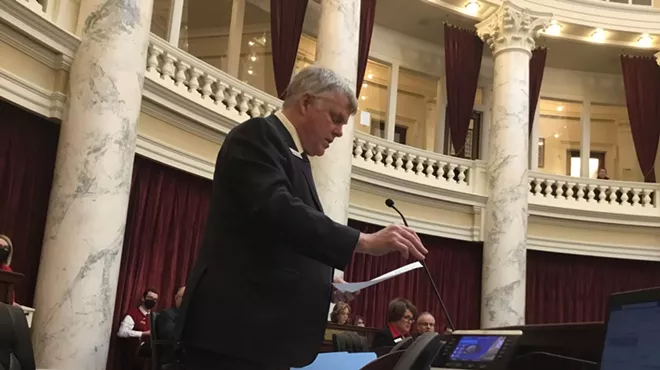

The coronavirus was spreading unchecked in Idaho, and Gov. Brad Little knew it.

While the entire nation has been hit with a massive COVID surge, Idaho is among the worst. Last week, Idaho ranked fifth in the nation for new daily cases per capita, lagging only behind Wisconsin, Montana and the Dakotas.

And now its hospitals are facing a crisis. In just two days last week, 172 new cases were reported in Kootenai County. And with 28 Kootenai Health staffers out sick with COVID themselves, the hospital in Coeur d'Alene was so full that patients were being sent elsewhere.

"Patients in North Idaho needing a higher level of care — whether for an injury, heart attack, or other reasons — are being transferred out of state," Little said at a press conference Monday.

For the past four months, as most of Washington state faced a host of Stage 2 coronavirus restrictions, Little had moved the bulk of Idaho to Stage 4 — opening nearly everything, from nightclubs to movie theaters, with very few distancing requirements.

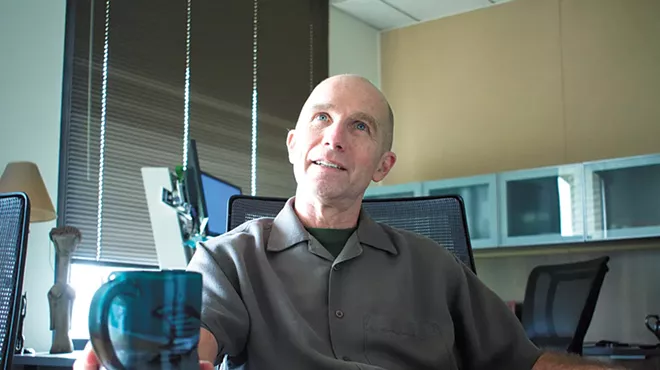

"From a business-economic perspective, there are no restrictions in place," Dave Jeppesen, director of Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, told the Inlander last week.

But in a press conference on Monday — as Facebook commenters flooded the livestreamed press conference with claims that masks don't work, that the virus was a hoax, and that Little wasn't a real Republican — the Idaho governor announced that he'd be moving the entire state back to Stage 3.

"Last week, things changed for the worse,"Little said. "This is unacceptable and we must do more."

Once again, indoor gatherings would be capped at 50 people, nursing homes would require masks, and the capacity of nightclubs and bars would be limited. Still, it was a lot less than the sort of restrictions still in effect throughout most of Washington.

Little defended his approach to largely leave the decision to impose further restrictions or mask mandates up to regional health districts and local cities. But the local-control approach, he acknowledged, was struggling to contend with an out-of-control virus.

Indeed, the same week Kootenai County's biggest hospital was overwhelmed, the Panhandle Health District defied the recommendations of doctors and ditched Kootenai County's mask mandate.

"In some parts of the state there has simply been insufficient efforts to protect lives," Little said. "Even in the face of an overwhelming need for action, the 'no-action' approach for dealing with COVID is not a responsible option."

THE VACUUM

Back in late April, Tommy Ahlquist, a former emergency room doctor and gubernatorial candidate, was bursting with optimism. Citing the success of the #CrushTheCurve effort he spearheaded, he argued that Idaho had built enough testing capacity to safely reopen.

While there was a spike of cases in the summer in Idaho, it had looked for a while like the state might dodge the worst of it: Idaho's economy was comparatively booming. Their unemployment rate had plunged. But today, Ahlquist's cheeriness has been replaced by horror.

"We are on fire here," he says.

While Idaho's rural nature had shielded the state from the spread of the virus for months, now he says it was going to be the state's "downfall as you watch all of these little rural counties on fire and have nowhere to go for health care."

According to Jeppesen, the director of Idaho's health department, the pandemic had spread largely due to activities outside work and school — the "backyard barbecues, the family reunions, the extended family Sunday dinners."

Experts blame COVID fatigue. We just want to get back to normal.

But Ahlquist also sees a failure of leadership.

Every one knew that "this fall and this winter was going to be a complete crap show. And it is," he says. "We're not prepared for this in any way, shape or form. It's going to get ugly. "

Months had gone by, Ahlquist felt, and almost nothing had been done to lead a statewide effort to coordinate testing and tracing or effectively convincing its population to wear masks. After Idaho built up its testing capacity, most of the tough decisions, he says, had been handed off to teeny school districts and ill-equipped health districts.

"Literally, it was all dumped on seven [health] districts that were not prepared for this. They said, 'Hey, figure this out. Each of you individually,'" Ahlquist says. "This is what it looks like in a leadership vacuum."

PANDEMIC HEALTH

Decades ago, Jeppesen says, the Idaho Legislature wrote into state code that the front-line response to a public health crisis would be the state's health districts.

"Idaho is a very independent-minded state," Jeppesen says. "A very local-control state."

David Pate, former president of the St. Luke's Health System and member of Little's coronavirus workgroup, says that the quality of the performance from the seven health districts has varied radically.

"The unfortunate thing is there are very few people on these boards — typically only one — who have any kind of medical expertise," Pate says.

With some of them steeped more in online conspiracy theories than medicine, the results have often been exasperating for public health professionals.

So while Panhandle Health District has a family doctor and a nurse on its board, the board has for 23 years also included Dr. Allen Banks, a man who, despite being touted on the health district website as a "world-renowned expert" in the controversial alternative medicine practice of "prolotherapy," is a Ph.D., not a doctor of medicine.

For months, Banks has unfurled a steady stream of unscientific claims at health district meetings — that lockdowns don't stop infections, that most COVID tests are false positives, that vast numbers of COVID deaths are mislabeled, that masks are harmful, vaccines are dangerously untested and that there wasn't any pandemic at all.

"Something's making these people sick, and I'm pretty sure that it's not coronavirus," Banks insisted at last week's Panhandle Health District board meeting.

To Pate, the meeting was "shocking and embarrassing."

Still, no sooner had the Panhandle Health District lifted the mask mandate for Kootenai County, the Coeur d'Alene City Council implemented its own mask mandate. Idaho remains a patchwork of various COVID policies: About half the state is under a mask mandate, and even then, some sheriffs have declined to enforce it.

Drive across the Idaho state line from Washington, and watch COVID cases surge and mask usage plummet: In Washington, over 90 percent of those surveyed over Facebook by Carnegie Mellon University say they wear masks most of the time. In Idaho, only 75 percent do.

IN CASE OF EMERGENCY, BREAK GLASS

Little argues that a state-wide mask mandate might be less effective than local mandates.

"We all know that if somebody locally asks us or tells us to do something, the compliance rate is a lot higher than it is from somebody from a higher level of government," Little said.

Yet much of Idaho does trust someone from a higher level of government: President Donald Trump.

At his press conference Little insisted that, in phone calls he's had with them, the White House coronavirus working group is firmly supportive of mask use.

Yet even after the president spent three days in the hospital being treated for the coronavirus, he's continued to mock masks and tweet that the "Fake News Media Conspiracy" media was exaggerating the virus to impact the election.

"I've been pandemic planning for probably two decades. We've known a pandemic would be coming," Pate says. "What never crossed my mind — which probably just shows you how naive I am — is that a public health emergency would be politicized."

Idaho politicians at all levels have had to contend with furious activists.

In August, when state lawmakers held a special session to discuss the coronavirus, they attempted to limit seating to follow social-distancing recommendations. Instead, they were greeted with an angry mob, maskless and armed, who shattered a glass door and rushed to pack the seats.

The next day, a supermajority of the Idaho House voted to end Gov. Little's emergency declaration — though the measure went nowhere in the Senate.

At times the anti-mask sentiment has resulted in showdowns with local officials: This month, an entire football game in Caldwell was canceled at halftime because a dad in attendance had refused to wear a mask.

The dad? Ammon Bundy — a far-right Idaho resident famous for leading a troupe of armed militants to occupy the federal Malheur wildlife refuge in Oregon in 2016.

Starting in March, Bundy launched People's Rights, using COVID-19 opposition to quickly unite an army of over 22,000 far-right activists across nine states. They didn't just protest outside government buildings. They targeted the personal homes of Jeppesen and Spokane Regional Health District Officer Bob Lutz.

"I would say, outside of the president, no one has had more of an impact on anti-masker sentiment than Ammon Bundy and the organization that he's put together," says Devin Burghart, executive director of the Institute for Research and Education on Human Rights, a national nonprofit that tracks far-right groups.

At last week's Panhandle Health District meeting, Walt Kirby, a 90-year-old Boundary County commissioner, recalled the backlash he had received for voting for the original mandate this summer.

"You guys have no idea the amount of heat I took because I voted for mandating the masks in Kootenai County," Kirby said. "There were a lot of people who were pretty damn nasty to me."

And so, despite believing that masks work, he voted to lift the mandate. If people wanted to be dumb and not mask up, he said, he didn't care.

"Nobody's wearing the damn mask anyway. All they are is just thumbing their nose at us," Kirby said. "People are dying. And they're gonna keep dying. And they're going to keep catching this stuff. And they're going to keep giving it to one another, right along until there's a vaccine."

And then, he predicted, there's going to be a bunch of people fighting against the vaccine.

"I'm just sitting back and watching them catch it and die," Kirby said. "Hopefully, I'll live through it." ♦