It's been nearly a dozen years since the economic crash of 2008, but the impact still haunts the housing market in Washington state.

"During the housing boom, housing production was about 53,000 units a year," says Jim Baumgart, housing policy advisor for Gov. Jay Inslee. "In the depth of the recession, it was less than 20,000 housing units a year."

Since the recession was caused by the crash of the housing market, long-lasting damage was done to the construction industry, as financing was frozen and experienced contractors and carpenters moved to other jobs. And the lack of tax revenue meant the state government slashed investments in affordable housing as well: Between 2010 and 2014, the state Housing Trust Fund, which awards money for affordable housing projects through a competitive grant process, was cut by 45 percent.

Still, even when the economy was at its lowest, Baumgart says, new residents kept flooding into Washington state. Between 2010 and 2012, over 29,000 new people moved here.

After the state came rocketing out of the recession, that population growth accelerated rapidly.

"Ninety-thousand people moved into the state last year," he says. "People are coming here looking for opportunity."

All the statewide efforts to build more housing, Baumgart says, have only recently broken even with population growth. And in Spokane, housing growth has been slower than in places like Seattle.

But this year's proposed House budget includes massive investments in housing: $15 million a year would be dedicated to supportive housing units like the ones built by Catholic Charities. Another $100 million would be poured into the Housing Trust Fund.

That's all on top of the legislation that gives a board of county commissioners or a city council the ability to vote in a permanent sales tax hike to further bolster affordable housing and a bill that hands Spokane a tool to spur new affordable housing in places like West Central.

"It feels like we're on the verge of the biggest game changer for housing in Spokane history," says the lobbyist for the Spokane City Council Erik Poulsen, "just because of the sheer resources that will be available for the city."

Still, in a state with high rents and one of the highest rates of homelessness, the question is whether all those reforms will be enough.

HOUSING INVESTMENTS

"I think we're falling behind. It's going to be really hard if we go into a recession," says former City Council President Ben Stuckart. "If you're already behind and you're falling behind, how do we make that up? Everybody assumed we'd have these low rents forever in Spokane, but that didn't happen."

Last week, Stuckart was named the next executive director of the Spokane Low Income Housing Consortium, a group of community organizations dedicated to promoting affordable housing.

And even before he was approached about the new job, he'd spent the last few months lobbying the Legislature for a bill to let a city pass a sales tax hike by a simple majority vote of the City Council, to fund affordable housing and mental health services. The one-tenth of 1 percent increase — an extra penny for a $10 purchase — in sales taxes could mean around $6 million extra for the city of Spokane.

"I think that's really important to have a local source of funding," Stuckart says.

But the sales tax bill directs 60 percent of the money to housing for veterans, domestic violence victims and low-income, disabled, elderly or mentally ill people. The rest would be used to fund mental and behavioral health programs.

On Monday, the measure passed out of the Legislature to be signed by the governor. The vote was almost entirely partisan, with only a single Republican in the Legislature supporting it. Republicans argued that citizens, not county commissioners or a city council, should be the ones deciding whether to impose a tax hike.

But to City Council members like Breean Beggs, it's an opportunity to pay a tiny cost and get a huge impact.

"It will literally transform lives," Beggs says.

THE BEGGS BILL

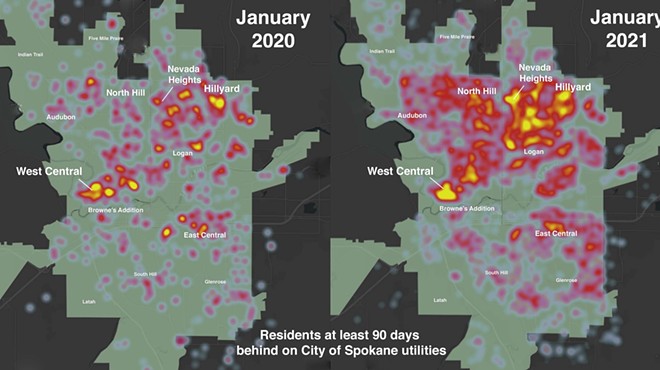

Beggs has been rooting for another housing bill as well: Its genesis goes back a decade, when a long strip of abandoned railway yard across the river from downtown Spokane started turning into Kendall Yards, a thriving cluster of dense townhomes and local businesses. The higher-end Kendall Yards bordered West Central, one of the poorest neighborhoods in the state.

"That's great," Beggs recalls thinking back then, "but West Central is going to get decimated."

Kendall Yards would send property values in West Central spiking, but that would make it harder for its residents to pay their rent.

Meanwhile, Kendall Yards was benefiting from a tax increment financing district, intending to direct extra property tax revenue generated from the new development toward public projects in the surrounding bordering neighborhoods. That extra money could be used for street lights, sidewalks, even the pedestrian bridge in Riverfront Park. But one thing it couldn't be used for? Affordable housing.

So way back in 2011, Breean Beggs wrote a letter to Washington state Sen. Andy Billig (D-Spokane) to argue that allowing tax increment financing money to be spent on affordable housing would help "substantially preserve and increase permanently affordable housing in Washington state."

"We could buy these houses up, retrofit them, and make them affordable," Beggs says now. "I couldn't get anything with legs through the Legislature."

Nine years went by. But last week, a bill from Washington state Rep. Timm Ormsby (D-Spokane) passed that includes Beggs' proposal to allow these funds to be spent on permanent affordable housing.

In part, that's due to the support from a developer — Kendall Yards developer Jim Frank, who calls the proposal "a win-win for developers as well as local communities and taxpayers."

MISSION NOT-QUITE ACCOMPLISHED

For some nonprofits that champion low-income housing, like Catholic Charities, all the extra money — whether from legislation, the Housing Trust Fund or a new city sales tax hike — addresses only a small piece of the problem.

"Drastic fundamental changes need to occur. I don't want to put up the banner that says 'Mission Accomplished,'" says Jonathan Mallahan, Catholic Charities' vice president of housing. "You're not going to subsidize your way out of the affordable housing crisis."

Mallahan says that Spokane and the state need to make big changes to their rules to clear the way for denser housing developments in the city.

While the state's Growth Management Act limits the ability of developers to build big housing developments in outlying areas, a thicket of regulations and the inevitable surge in neighborhood opposition to apartment complexes means that building in the middle of a city is difficult.

Washington state has chipped away at regulations restricting condo developments and "accessory-dwelling units" — the basement bedrooms or backyard cottages you might rent to your mother-in-law. But Washington hasn't done anything as dramatic as Oregon did last year, when it changed the definition of "single-family zoning" to allow duplexes in every single-family neighborhood, no matter how snooty. Instead, it's left many of the most important housing policy decisions up to the local politicians who risk voter backlash anywhere they want to build affordable housing.

"Local control maybe isn't the best thing for zoning," Stuckart says. "At some point, if the state wants to continue to have a Growth Management Act, then you're going to have to do something to force cities to come along." ♦