Seth Gray is wearing his dead brother’s clothes. In front of a high school gym packed with mourners, he stands in Brandon’s torn jeans, yellow string holding the back pockets together, and the weathered jersey his 26-year-old brother used to wear when the two of them would snowmobile in the boonies of North Idaho.

Gray strips off the jersey, revealing a black shirt with pink writing, a memento he’d bought with Brandon at a local shop. The shirt reads: “I PUT THE FUN IN FUNERAL.”

“Some of you may think this dress is inappropriate,” Gray tells the assembled grandparents, mayors, union heads, mining company CEOs and coworkers, “but I don’t care.”

The crowd chuckles. He had told the mourners that this funeral would not be sad, and now he’s delivering on that. He jokes about the ’70s-porn-star mustache that his brother had been growing and how he’ll have that on his lip for eternity. And he talks about Brandon’s pride and joy, his Ford F-250 Super Duty, now parked outside among the many trucks of Mullan, Idaho.

Brandon had tricked out his rig with money he had made at Lucky Friday Mine, and, like many mourning him that day in November, he’d benefited from a boom in silver. Prices are high. Mines are re-opening and expanding. Companies are turning record profits.

But it’s come at a cost. Brandon Gray was the second person to die at Lucky Friday Mine last year. In December, less than a month later, seven miners were injured in a rock burst and later rescued.

Federal regulators shut down the mine last month while its main shaft is cleaned, and the mining company, Hecla, says it could take up to a year to complete the repairs. In the meantime, the fortune of Silver Valley hangs in the balance, as some 200 well-paid miners are out of work.

People are angry — less, it seems, with Hecla than with the feds for interfering with the mine. Indeed, in this slice of North Idaho, silver isn’t just a business, it’s a way of life.

‘GOOD GEOLOGY’

Army Lieutenant John Mullan was traveling with an army of workers from Walla Walla to Montana in 1860 when they cut through a pass and into a valley easy of present-day Coeur d’Alene Mullan and his workers encountered a prospector there.

The man had gold. Mullan saw it and promptly gave the man provisions and money and told him to scram. He didn’t want his men running off in search of riches, according to Troy Lambert, a Silver Valley history buff at the Wallace District Mining Museum.

But rumors of gold made their way out of the valley, and as prospectors flooded the area, they eventually stumbled upon outcroppings of galena, a lead ore infused with silver. The prospectors had dug out nearly all of the region’s gold in the first three years of the rush, so they turned to silver.

“The Coeur d’Alene Mining District,” as it became known, is now considered one of the top five silver-producing districts in the world, says Earl Bennett, a former dean of the College of Mines at the University of Idaho.

“Ore deposits are often found where you got good geology,” Bennett says. “And good geology has mountains.”

The valley is a narrow strip of land, running from Fourth of July Pass in the west to Lookout Pass on the Montana border. It’s a place familiar with booms and busts.

There have been good times, like the 1880s and 1890s, when mines were springing up all over the valley and the wealth flowed across the Inland Northwest. Spokane became one of the richest cities in the world, shipping the valley’s silver east to Minneapolis, Chicago and beyond.

“People in Spokane thought, in 1893, that with all the wealth … this was going to be like San Francisco,” says Bill Stimson, an Eastern Washington University professor, who wrote about the city’s history in his book A View of the Falls.

But there have also been downtimes, like the 1980s, when a silver bubble burst, causing prices to plummet and operations — including the valley’s most productive mine, Bunker Hill — to shut down.

“Everything tanked in the 1980s,” Lambert says.

“Mining’s always been a cyclical thing in the valley … but that was probably the lowest.”

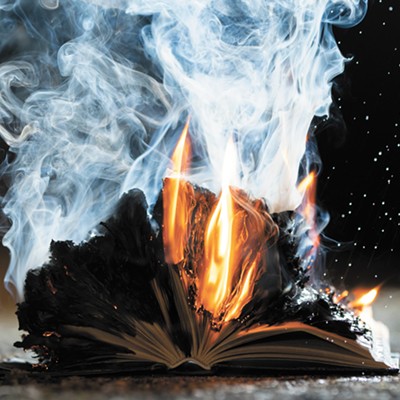

And there have been tragedies: In 1972, a fire at the Sunshine Mine killed 91 miners, leading to new safety devices like the emergency respirator every miner carries today. Not long after, in 1977, Congress established the Mine Safety and Health Administration to regulate the industry.

Finally, in 2004, prices started to creep up, prompting new interest. Meanwhile, Hecla, founded amid the boom in 1891, announced plans for two major expansions at Lucky Friday Mine. A new shaft was proposed that would reach down 8,800 feet and, the company says, keep the mine producing silver past 2030.

By 2011, silver was hovering consistently around $30 an ounce and at one point nearly reached $50. Hecla announced that it would begin exploring whether to reopen the Star Mine, and U.S. Silver, which owns Galena Mine near Osburn, Idaho, says they plan to reopen their mine’s deeper caverns, as well as bring the shuttered Coeur Mine back into production.

New companies are also forming to reopen longshuttered mines. According to filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, a company called Sunshine Silver Mines Corporation is eyeing the Sunshine Mine, which has produced the most silver ore of any mine in the valley. Another company is looking at reopening Crescent Mine.

Why the boom? Just look at your iPhone. Or your shirt. Or your portfolio.

“A smartphone and a tablet and a computer, all of those take a little bit of silver,” Hecla’s president and CEO, Phil Baker, says. “In some cases a quarter of a gram, in some cases a gram, are in those things to work.”

Besides that, there are solar panels, batteries and clothing, not to mention silver’s use as an investment.

At the start of 2011, Hecla announced that the $418.8 million made in 2010 was a company record. But then last month, when officials announced that Lucky Friday would be closed for repairs, Hecla’s stock dropped 20 percent in a single day.

IF IT COULD HAPPEN TO HIM

Among miners, Larry Marek was known in one of two ways: either as one of the best miners in the Silver Valley, or the best.

“You meet some good miners, but not like him,” recalls Ron Barrett, a miner who first met Marek at the Sunshine Mine. “You couldn’t ask for a better person.”

The mustached 53-year-old came from a family of miners. Some of his brothers work at Galena. He worked at Lucky Friday, where he was partnered with his brother Mike.

A report produced by the Mine Safety and Health Administration details Larry Marek’s last day. On April 15 of last year, Marek showed up to work the night shift at Lucky Friday. He went down 6,000 feet and, with his brother, found his way to a “stope,” the horizontal floors of the mine where most of the blasting and drilling takes place.

Between the natural heat of being deep underground and the equipment used to mine, a stope can be a hot place. Marek set up an air conditioning system and then started watering down the rock and ore to cool it.

Larry Marek was on the west stope; Mike Marek on the east. Mike looked over at his brother and saw his headlight.

“[Mike] heard the ground caving in over in the west stope and felt a tremendous rush of air,” the report reads.

Mike ran to find a pile of rocks where his brother had been. He found a co-worker, told him about the collapse, then ran back to start moving rocks by hand.

There was hope, at first, that Marek was trapped but surviving off the compressed air and water from the drill he was using.

Nine days later, Marek’s body was found under a 30-foot-high pile of rocks. The valley mourned.

“Being that it was Larry, I think there was a kind of an attitude of, ‘If it could happen to him, it could happen to everyone,’” Barrett says.

Brandon Gray was in the mine when the collapse killed Marek, and he also knew Tim Bush, who died in 2010 at the Galena Mine. But Gray was happy with his new job working for Cementation U.S.A., a contractor hired by Hecla to build a $200 million shaft, says his mother, Laurie Gray.

Gray also came from a mining family, and his bosses would say, “I think he’s going to be a natural,” Laurie Gray recalls. She knew the money her son would make. The average miner rakes in $70,000 a year, more than double the average wage of other jobs in the county. But she also understood the risks.

“As a mom of a miner, I always told him I loved him and be safe,” before he left for a shift, Gray says. She did that on Nov. 17, the last time she saw him.

That day, Brandon was working in a “bin” — a silo where leftover rock and ore from the construction of the shaft were stored. For some reason, the muck underneath his feet started moving, “like the sand in an hourglass, as Baker, the Hecla CEO, would later describe.

Gray was being sucked under by small rock chips, despite his mining partner’s attempts to save him, and despite the harness he wore, which Baker says didn’t engage because he wasn’t moving fast enough.

Gray was eventually pulled out and taken to the hospital. Two days after the accident, he was taken off life support.

“He was an organ donor,” his grandfather, Darrell Gray, says. “So the boy is still alive as far as I’m concerned. He might be in other people, but the man is still alive.”

A MILE DOWN

A few weeks after her son’s funeral, Laurie Gray was back in the same gymnasium in Mullan for a Christmas party when the ground started to rumble.

“We always knew what a rock burst felt like,” Gray recalls. “My heart just dropped.”

Over a mile below, Ron Barrett was knocked off his feet.

In his nearly 15 years as a miner, he’d heard the loud boom of rock bursts in the distance. But he recalls hearing nothing as he was thrown to the ground and knocked unconscious.

When he woke, he couldn’t move. A guy next to him started kicking his own legs free, and Barrett says that he soon found that he, too, could start moving. He wiggled himself out from under the rocks and saw that the six others he was with “were beat up bad.”

Since the accident, Barrett has been off work. He walks stiffly. He says the doctors have told him that it’s muscle spasms.

Rock bursts like the one that trapped Barrett are among the most uncontrollable hazards underground, says Bennett, the former mining dean. “You got a mile of rock sitting over the top of you,” he says. That means the rocks are under pressure, and when that pressure releases, rocks can literally explode.

On Dec. 14, the mine had sent Barrett and six others to the area of a previous rock burst to install a culvert intended to further cushion against any further blasts.

Typically, Baker says, rock bursts release stress underground, so having another blast in the same place is unlikely. “For whatever reason, that stress was reintroduced,” he says.

Inspectors from MSHA arrived two days after the accident to carry out a “special emphasis” inspection of the mine. Developed after an explosion at the Upper Big Branch coal mine in West Virginia killed 29 miners, these inspections “are targeted at mines that merit increased agency attention and enforcement due to their poor compliance history or particular compliance concern,” according to Amy Louviere, an administration spokeswoman. Fifty-nine citations and 16 orders were issued against the mine, Louviere says, 22 of which were against contractor Cementation U.S.A. The citations range from insufficient ground support to unclean work areas.

One of the citations was for sand that had built up on the sides of the main shaft of the mine. The worry is that the sand could build up, break off in chunks and hit a cage going down into the mine, Baker says.

Hecla was told to clean the shaft, and when the administration returned on Jan. 6 to check on the repairs, they told Hecla that the shaft was still not clean, and ordered it shut down until it could be cleaned thoroughly.

“This shaft has operated safely for the past 30 years,” Baker says. “However, MSHA currently believes that a clean-down from the surface to the bottom is the best way to remove the material that has deposited on the shaft.” And that will take until about 2013, he says.

In an email, the administration disputed that it would take a year to clean the shaft.

“While MSHA cannot speculate how long it will take to rehab the mine, the agency does not understand why the operation might be shut down for a year, as the operator has suggested,” Louviere writes in an email. “We understand the economic hardship associated with being out of work, but our primary concern is that no more deaths or serious injuries occur at this mine.”

This was not Hecla’s first tangle with the mining administration in recent months. In November, the agency released its final report on the death of Larry Marek, faulting Hecla for allowing the stope that Marek was mining to be so close to another stope. Baker rejects their report. “The MSHA report, it makes statements, then doesn’t provide the information to substantiate their position,” he says. He also vows to appeal any citations issued to Hecla.

As a whole, however, the mining industry is becoming safer. The mining administration reports mining deaths in 2011 were at their second-lowest number since 1910.

BLAME GAME

The valley met news of Lucky Friday’s closure with rage and resignation.

“This is federal government arrogance at its height,” wrote mining columnist David Bond on Silverminers. com. “It is brazen and it reeks of ass-covering.”

Meanwhile, Idaho Gov. Butch Otter held a town hall in Wallace. His spokesman, Jon Hanian, says the governor is talking with administration officials about the mine closure but declined to elaborate further.

A Hecla spokeswoman estimates that of the 160 Hecla workers laid off, 60 have been moved to other Hecla mines. Of the about 100 Cementation employees, 50 have been kept on to clean the shaft, and the rest were laid off.

If the layoffs last for a year, unemployment in Shoshone County could exceed 17 percent and the valley could lose $25 million, according to Alivia Metts, a regional economist with the Idaho Department of Labor.

And the number laid off could be larger once contractors and businesses relying on the mine are factored in, though Baker says some will still be employed on the cleaning of the shaft.

In response, the Department of Labor held a job fair two weeks ago. At the door to the gymnasium of the Wallace Junior-Senior High School, two former co-workers cross paths. They know each other from Lucky Friday.

“Did you get hired?” Jerry Hagaman yells to Al Wilks. “I’m here, aren’t I?” Wilks replies.

Inside, a few guys in Carhartt jackets sit on bleachers filling out job applications. On the floor, groups ranging from North Idaho College to the U.S. Army talk to jobseekers. U.S. Silver hands out applications for its positions at Galena. They’d already hired seven people. Barrick, another mining company, had also made 19 offers, but that was for a mine in Nevada.

Hagaman ended up landing a job with a contractor at the Star Mine. Wilks, with only 10 months of experience, was having trouble getting work and was looking for guidance at the job fair.

Both Wilks and Hagaman are typical of the Silver Valley miner: in it for the money, looking to stay in it, reluctant to leave the valley, accepting of the risks.

“It’s safer than it’s ever been,” Hagaman says of his job for the last six years. “And I would rather die in a rock burst than starve to death.”

Comments? Send them [email protected].