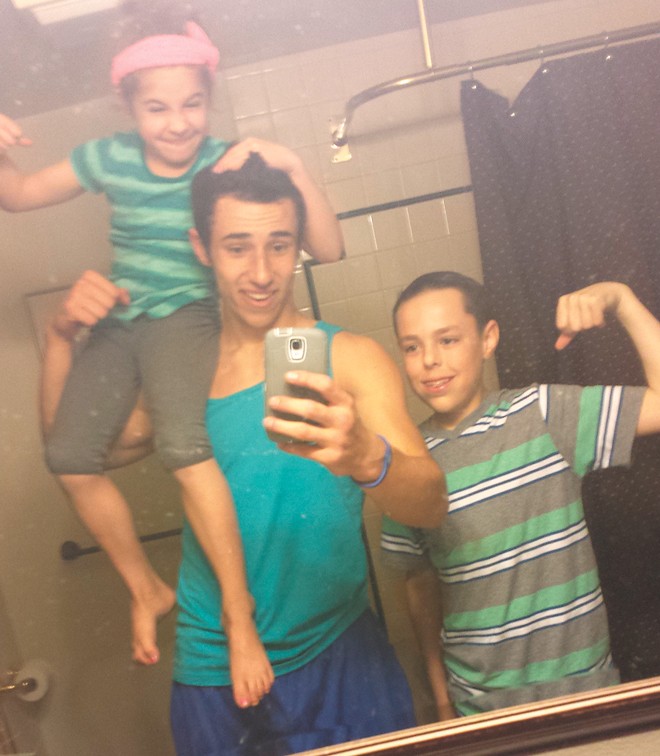

His phone is buzzing again. Isaiah Wall is 19 and handsome, with freckled cheeks and biceps from his days as a wrestler. Like any teen, he spends an ungodly amount of time on his phone — checking in with his mom, seeing who wants to party and confirming his work schedule at a gun-holster manufacturer in Post Falls.

But mixed in between those messages are texts from someone named Josh, demanding that Isaiah get him more drugs.

"Can you order up from S for tomorrow. 1 zip, same as last time," Josh texts Isaiah, using street lingo for an "ounce" of crystal meth.

"I was gunna talk to you about that," Isaiah replies. "I think it'd be weird going from a gram to an ounce. Can I order up a quarter for tomorrow and do the oz a few days after?"

"Go for the full," Josh writes. "It's not for you remember? He said he had it so let's go for it. You're getting it for 'friends' so don't worry."

By all indications, Josh isn't a friend, but rather Detective Josh Clark with the Idaho State Police; Isaiah had been roped into helping the ISP investigate drug trafficking in the area, Coeur d'Alene police tells the Inlander. Often promised leniency for alleged crimes, informants are used on the front lines of the drug war, with little training and few safeguards, as they perform high-risk police work on the cheap. Critics complain that the practice often exploits vulnerable people, many of them unstable and/or drug-addicted, with little regard to their safety.

The Idaho State Police won't confirm whether Isaiah snitched for the agency, and through his supervisor, Clark declined an interview request. However, texts and Facebook messages from Isaiah's phone match up perfectly with undercover drug buys detailed in a felony case in Kootenai County. The arresting officer in that investigation? ISP Detective Josh Clark.

Isaiah's mother, Courtney McKinnie, says she didn't know her son worked as an informant, until one day she went through his phone and found back-and-forth text messages like this exchange from May 23:

Josh texts at 9:10 pm: "They not awake yet or they can't handle the weight?"

"I've messaged both and they just haven't texted back," Isaiah responds. "I don't know if it's cuz they can't get it right now but if I hit them up anymore it will just look weird."

"Ok," Josh writes. "We'll wait. Gotta look natural."

Six days after that exchange — and just 11 days after he started texting with Josh — Isaiah is found dead from a single gunshot to the head. There are no known witnesses, and while Coeur d'Alene police are still investigating, they say they have yet to find any connection between his work as an informant and his death.

In any case, Isaiah's mother isn't convinced by the explanations she's been given.

"I just have been in the dark this whole time," McKinnie says. "Nobody's contacted me or anything. And it makes a big difference on the grieving whether Isaiah took his own life or whether it was snuffed out."

By the time he's 14, Isaiah's watched his father, Marcus Wall, pinball in and out of prison for various felonies. Each time, his mom says, it tears him up.

"Marcus is Isaiah's hero," McKinnie says.

Around this time, McKinnie herself starts to unravel. She's been working as a dental hygienist, making decent money, but struggles to raise Isaiah and his two younger siblings on her own. The guy she's dating doesn't really warm up to the kids. She stays out late and drinks, leaving Isaiah to take care of them.

"I robbed him of a lot of his childhood in having to babysit his sister and brother with me out having fun," she says. "Lots of guilt."

Without much supervision, 14-year-old Isaiah is left to figure it out on his own.

One night around 11 pm, he and a friend are riding bikes in the neighborhood where he grew up, just north of the Coeur d'Alene Resort. Police in an unmarked car stop the boys because they don't have lights or reflectors. They find a foot-tall bong in Isaiah's backpack, according to the police report.

Prosecutors eventually drop the case, but Isaiah's contact with the justice system continues. He regularly breaks curfew and skips school, and McKinnie kicks him out of the house as a consequence, friends say. He sleeps at a neighbor's or crashes with buddies.

McKinnie feels that she's lost control and calls the police.

"I was terrified," she recalls. McKinnie pauses with a sigh. "I'm so stubborn. I feel bad about it now. All those times I called the police I thought I was doing what I should have done."

A judge ends up sending Isaiah to a youth ranch for troubled teens near Yakima. He escapes more than once, his mom says, and hitchhikes all the way back to Coeur d'Alene. One time, she recalls, he arrives at 3 in the morning, the soles of his shoes worn through.

Matt Beever, his fourth-grade teacher at Classical Christian Academy in Post Falls, sees potential in Isaiah as a natural leader and a fierce competitor. At recess, Isaiah organizes soccer and football games without being condescending or bossy, Beever says. And come Christmas time, when other students gave Starbucks gift certificates or golf balls, Isaiah gives his teacher a stack of his favorite baseball cards.

"Knowing how much he was into sports and how much the cards were worth, I tried over and over to give them back, but he wouldn't let me," Beever says. "I continued to stay in touch with him through the years, because I knew he didn't have enough voices in his life pointing out the good, positive part of him and far too many pointing out the negatives."

In eighth grade, Isaiah starts to wrestle in school, McKinnie says, to help deal with his behavioral issues. He goes undefeated in his first year. He eventually moves back home, bringing with him his best friend, Chris Anderson, to live with McKinnie. She pushes them to finish high school, but the boys have other ideas.

They work odd jobs and hustle for money. They paint a garage in exchange for $200 each. Isaiah, about 17 at the time, buys an ounce of pot and flips it for a profit, Anderson says. Then he buys more. At his peak, Isaiah moves about three pounds of weed in a month, Anderson estimates, and his network of connections grows. Isaiah knows people, and eventually he's slinging small quantities of cocaine, some acid, mushrooms or Molly when he can get it.

Friends start calling him Frosty.

"Because he was always making it snow," Anderson says, adding that Isaiah drew a line at heroin and meth "because that is some bunk ass shit."

Girls call Isaiah "Hollister," after the trendy SoCal clothing line. He stands over 6 feet, with six-pack abs, diamonds in his ears, a gold chain and a watch to match. He's popular with girls, but one stands out — Aimée Grossglauser. She's different. Kinda quiet with straight blonde hair down to the middle of her back and a nose ring — his first love.

They date on and off for about 2½ years, and after breaking up manage to stay good friends, Grossglauser says.

In April of this year, they take a drive around Lake Coeur d'Alene to catch up. They park, smoke a bowl and let their feet hang over the side of a dock. Grossglauser tells him about her classes at North Idaho College. He talks about moving to a new apartment next month and says he's been working for a gun-holster manufacturer and doing construction on the side for his grandpa.

"He was saying how he doesn't want to be in the same stuff anymore," Grossglauser says, referring to his drug-dealing days. "He'd been doing this for a couple years and it's not really going anywhere, and he was just tired of it."

On Facebook, he posts about fast cars, guns, Donald Trump (mostly because of gun rights), girls and partying. He's amassed more than a thousand friends, but his posts also paint him as a high-spirited teenager who often feels alone and helpless.

"I'm so over this bullshit. I just need a solid place to live," he writes in June 2015.

Later, he posts: "Nobody ever hears anyone's cry for help until it's too late."

At times, he wants to give up: "Been thinking about dipping out for a while. There's not to much to offer for me here."

Then there's the text message Isaiah sent Grossglauser the month before he began working for the Idaho State Police, hinting that he's begun to look forward:

"It's hard to find people nowadays with actual goals. Especially the same goals as you. I feel like a lot of people just live day by day and don't really give a f—- about down the road, they just live in the here and now. That used to be my problem, but I've actually start[ed] to consider my future and what I want to do in life, and where I want to be."

At 8:17 am on May 18, 2016 — the day his father was to be sentenced for a parole violation — Isaiah Wall's phone rings. He lets it go to voicemail, but the calls continue. He finally picks up — it's the Idaho State Police.

The person on the other end of the line tells Isaiah they know he was involved in a hit-and-run two days before. He needs to come immediately to the ISP headquarters in Coeur d'Alene, according to Anderson, who says he was with Isaiah that day. (ISP officials have refused to confirm whether it employed Isaiah as an informant.)

This, Anderson says, is what follows:

Isaiah tells the caller he has no clue about the alleged hit-and-run. While still on the phone, he walks around his car. There's no damage that he can see, he assures the caller.

We need to inspect the car ourselves, the caller tells Isaiah. Get down here immediately.

The two teenagers hop into Isaiah's forest-green Mustang — 22-inch rims, speaker box in the back — and go to the ISP building on West Wilbur Avenue. A receptionist tells them someone will be out shortly, and they go outside to wait and smoke cigarettes.

Two Idaho police officers show up.

"Isaiah Wall?" one says.

Wall raises his hand.

"You're under arrest."

Isaiah asks why, Anderson says, and as they put him in handcuffs, one officer answers quietly in his ear:

"For being a motherf—-in' drug dealer."

The officers tell Anderson to beat it, and he hops a bus to a friend's house to wait. Isaiah shows up hours later. There was no hit-and-run, he tells Anderson. There weren't even any charges against him — at least nothing officially filed, according to court records. Isaiah tells Anderson that detectives took him into a conference room and told him they'd been watching him for months; someone "very close to him" had snitched, though they wouldn't say who.

The detectives tell Isaiah he's facing 10 years in prison for cocaine trafficking, Anderson says. So he has two options: face the charges, or cut a deal and cooperate. They want him to do an undercover drug buy that very day, Anderson says, but Isaiah pleads to postpone it. He has to make it to his father's sentencing hearing at 3 pm.

That afternoon Marcus Wall is sentenced to more than a year in prison. Isaiah is devastated.

Soon "Josh" will enter his life.

"Grandma I don't know what to do," Isaiah texts at 10:46 am on May 24. "I always feel like my life is falling apart."

Minutes later, he's back to texting with Josh: "I've hit both of them up this morning. S hit me up at like 12:30 last night and I said to push it to today."

"What's he got?" Josh asks.

"He just said dope. And it's going super fast."

"OK. Set it up for 4 ish. See if he has a full for you and how much," Josh texts, adding later, "Plan to be at the office at 315 and we'll go get it."

Isaiah is nervous that Josh wants him to pop in without getting the green light from the drug dealer.

"Wait what?" Isaiah asks Josh. "You want me to just say I'm on my way even if he doesn't answer? That'd be realllly weird and definitely not like me. I ask everyone to come over before I do and if I just show up wanting an OZ meth when I've only pick[ed] up a gram from him he'll think that's shady."

Josh responds: "Hey calm down bud we're not gonna go cold calling. We'll wait till he says to come over but we have to plan for it."

By 5 pm, it's finally set up.

Detective Josh Clark recounts in a court records a drug buy that day, but doesn't name Isaiah. In sterilized legal language, he writes about an unnamed informant, who leads detectives to location of the drug deal. Detectives listen to the conversation through a wire.

"They want to get an ounce soon," the informant says, according to Clark's report.

"Ok, no trouble," the dealer says.

Later that week, about 3:30 am on May 28, Isaiah sits by himself sipping a beer. He can't sleep. He's done three controlled buys within the past two weeks for over an ounce of meth, according to court documents the Inlander linked to Isaiah. All three buys were from the same person, more of an acquaintance than a close friend. But later in the week he's supposed to snitch on a buddy who's fallen into harder drugs recently.

Isaiah starts messaging friends. He's going crazy by himself, he tells them. Some respond, but it's too late to come chill. Isaiah finally falls asleep.

Samm Tarkington recalls seeing Isaiah at a party about a week before his death. They had been flirting with the idea of dating for a few months at that point, she says. He was sitting on a table with his head in his hands. She didn't know what was wrong, but she had never seen him that stressed before. Gone was the carefree, confident kid.

"He was like, 'I want to tell you, but I can't talk to you about this,'" Tarkington says. "It was weighing on him heavily."

The party's over. The girls are gone. Isaiah's buddy, Chris Anderson, left hours ago. Another friend, Ricky Robinson, is asleep in the house. It's the early morning hours of May 29; Isaiah and a friend named William Krigbaum are the last ones up, sitting around an empty fire pit in the backyard of a house where Isaiah's been living.

The stars are out.

And Isaiah and Krigbaum are out of their minds after dropping acid, Krigbaum says. While they're tripping, Isaiah twirls a .40-caliber handgun on his finger, ejects an unfired round from the chamber and snatches it from the air.

At 2:26 am, Isaiah texts one of the girls who left earlier: "Thanks for saying bye."

"I'm holding my girls hair back. You know I wish I could've just stuck with being a homie."

Isaiah, at 2:39 am: "Please come back."

At 2:41 am, Samm Tarkington calls him for help with her drunk friend. It's a short conversation; Tarkington can hear Krigbaum in the background, and the two boys are laughing.

Now it's about 4:30, and the sun starts to rise. Krigbaum goes into the kitchen to get a drink of water. He moves to the couch to pass out, Krigbaum will later say, and Isaiah is still in the backyard, with his pistol, alone.

A gunshot wakes Krigbaum.

He says he staggers off the couch and stumbles into the yard. Isaiah is laying on the ground, an open Zippo lighter and a gun at his feet. A pool of blood expands under his head.

Courtney McKinnie can't sleep. Guilt crushes her — guilt for every stupid argument with Isaiah, for calling the police on him when he was a kid, for every time he needed his mom and she wasn't there.

Then she gets his iPhone back from the funeral home and begins her own investigation. She methodically combs through his texts, his Facebook and Instagram accounts, looking for clues. She stops on a thread of messages with Josh. She takes pictures of the texts and of his location data placing him at Idaho State Police headquarters in Coeur d'Alene three times in the past month.

She finds a note Isaiah left for himself in his phone on May 26, noting his own license plate number and that of a "DEA" car.

McKinnie has a thousand questions. She records her meetings with Coeur d'Alene police detectives, with people at the coroner's office, employees at the funeral home and several of Isaiah's friends. She pays to have all the data extracted off of his phone and hires a private investigator.

She isn't ruling out the possibility that her son took his own life. She knows he struggled with depression and is upfront about his difficult home life and her role in all of that. But things aren't adding up, she says:

• Isaiah is right-handed and, friends say, he always fired guns with his right hand. But the police report indicates he fired with his left hand and then fell on his left side.

• Isaiah was planning to move into a new apartment the very next day. His stuff was packed in the car, and he'd been texting his new roommate in the days — and hours — leading up to his death. McKinnie was supposed to help him move.

• No autopsy was performed. Neither the Kootenai County Coroner's Office nor the Coeur d'Alene police ordered one. The coroner, nevertheless, ruled the shooting a suicide after looking at the scene. (A Coeur d'Alene police detective tells the Inlander an autopsy might have been ordered if investigators had known he was an informant at the time.)

Six months after Isaiah's death, the Coeur d'Alene police investigation is still not complete. In a 25-page report released to the Inlander, there is only one mention of Isaiah's work as a drug informant, from an interview with Krigbaum more than a week after Isaiah's death. There is no record of any communication with the Idaho State Police.

CPD Detective Jared Reneau says there are still a few loose ends he needs to tie up, but can't comment further at the risk of jeopardizing the integrity of the investigation.

Reneau met with McKinnie earlier this month. He tells her: "I was at the crime scene. From everything I saw, there wasn't anything that was overly suspicious."

But what if he was murdered? McKinnie asks Detective Reneau if she should be worried about the guy who's going to jail because of Isaiah. What if he wants revenge on her or her family? Reneau doesn't have many answers. He says the Idaho State Police don't keep CPD in the loop.

"I've just been left in the dark to do my own investigating," she tells Reneau.

The conference room inside the Idaho State Police headquarters in Coeur d'Alene is flooded in fluorescent light, with a long table surrounded by chairs. This is allegedly where Isaiah agreed to become an informant.

Seated around the table now are two sergeants as well as the captain in charge of the district, John Kempf, a tall, veteran investigator with graying temples.

They've agreed to speak generally about the agency's use of confidential informants, but say they can't comment on whether Isaiah worked for them. Doing so, they say, would betray any potential deal to keep his identity a secret and would undermine the entire confidential informant program. No one will want to secretly feed them information if they put one of their sources "on Front Street," as they say.

Even if that source is dead.

Kempf has worked drug investigations for the Idaho State Police for 16 years and now teaches new detectives how to build drug cases — one of main functions of the Idaho State Police. Detective training includes a "significant" portion of an 80-hour class dedicated to working with informants; in his curriculum, Kempf draws from questionable, dangerous and reckless examples of informant use from across the country for lessons on what not to do.

The Idaho State Police refuse to release any policies or guidelines related to informants, citing a clause in state law exempting information that could reveal investigative techniques or the identity of a confidential informant.

Around the conference room table, Kempf and his two detectives remain ardent in their defense of secret sources.

"We'll always have confidential informants," Kempf says. "Always. They've always been a part of narcotics work and always will be. They are a necessary tool to do drug investigations."

The biggest advantage of using confidential informants, Kempf says, is their intimate knowledge of "the drug world or drug culture they're involved in." Both socially and legally speaking, confidential informants have access to places and people that detectives typically would not. For police to walk into a drug house, or any house for that matter, they need a warrant.

As to the training that informants receive to conduct police work, Kempf says: "The short answer, without giving specifics, is... they were involved in this criminal activity before we met them. So they know the street better than we do. They oftentimes know the person they're buying drugs from much better than we do. They know how to operate, they know whether or not they have weapons."

There are safeguards in place, and the program is closely and continually scrutinized, Kempf and his two sergeants say, declining to give specifics. Kempf adds that they have a checklist of criteria to assess potential informants, including whether they have a history of depression or other mental health issues.

Typically the problems arise, Kempf says, when informants tell on themselves. He adds, however, that he isn't aware of an informant in Idaho being killed on the job.

"The first thing we say is, 'Don't tell anybody,'" Kempf says. "It's not because we're worried about our case, but we know this could go sideways the more people are involved."

Alexandra Natapoff, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles and one of the nation's leading experts on the use of informants, says police and prosecutors have near-complete discretion in the use of confidential informants as a matter of public policy. The constitutional rights of defendants, she argues, are excused in the name of keeping a source of information anonymous, and vulnerable people — perhaps young, addicted to drugs, unable to afford an attorney or otherwise incapable of asserting their rights — are sent to do the work of a trained police officer.

Rarely, she says, do the specific details of that work come to light.

"Like any risky public policy, sometimes using informants is worth the risk," she says. "But right now the system is not designed to evaluate the true costs and benefits of informant use — the public is asked to take it on faith. That needs to change, especially where we know that the costs to the young and vulnerable are particularly high."

She points to one shocking example from Florida in which police there enlisted a small-time, college-aged pot dealer. Rachel Hoffman, the subject of a New Yorker exposé on young confidential informants, was sent to buy a large quantity of drugs and weapons back in 2008. The dealers found the wire in her purse and killed her with the very gun police wanted her to buy.

The reckless use of informants — leading to their torture or murder — often goes unnoticed, Natapoff says, unless their families have the means to hire attorneys and see the cases through lengthy legal battles.

For Natapoff, that makes exposing Isaiah's story — a case of kid with little support or resources — all the more significant.

"Part of the tragedy is that for people like Isaiah, who've already been devalued by the system, their stories never get told, and their names are never heard," she says. "Logically speaking, there are thousands of Isaiah Walls all over the country, and we will never know about them because their friends and family don't have the resources to produce an outcry and raise public attention."

She adds: "It's possible that if it was a suicide, it may have been because he felt despondent and trapped because he was an informant. For someone in his situation, you could imagine how he could see that as a death sentence."

McKinnie sits in the driver's seat of her navy-blue Pontiac Grand Prix, parked in a cemetery not far from where Isaiah grew up. You can see his grave from the road. It's the one with the statute of an eagle — his favorite football team — flowers, photos and a notebook.

Smoke from her cigarette billows out of the car and into the bright sky. Her brown hair is twisted into a nest on top of her head. She's wearing a baseball T-shirt with blue sleeves and a gold watch. Both were Isaiah's.

She feels better having spoken with detectives, though she has yet to hear from the Idaho State Police. She is still unsure of when, or if, she'll have answers.

"My son was just kind of tossed aside as a drug dealer, as disposable, somebody not productive in society," she says. "And that's the worst part for me."

She visits Isaiah's gravesite and posts to his Facebook page almost daily; on Sunday, Nov. 20, she's invited friends and family to his grave to celebrate — it would have been Isaiah's 20th birthday. In the meantime, she's left poring over pictures and videos of him saved on her phone. She stops on a screenshot of one of the last communications Isaiah received on his phone.

On May 31, two days after Isaiah died, Josh texts again:

"Wednesday going to work?" ♦

WHEN THINGS GO BAD

By 1993, research shows that the use of confidential informants spiked by nearly 200 percent compared to only a decade before. That spike is driven largely by the war on drugs, according to Alexandra Natapoff, a professor at Los Angeles' Loyola Law School and a leading expert in the use of informants. Police recruited scores of young, vulnerable and often drug-addicted individuals to do the work of undercover officers. That risky and dangerous work is shielded from the public view. Many informants don't survive.

• In 1996, Kentucky State Police asked LeBron Gaither to testify against a drug dealer he'd set up. Gaither (pictured) was 18 at the time, but news reports indicate that police recruited Gaither as a 16-year-old when he entered the juvenile system. The day after Gaither's testimony, police sent him back out to buy more drugs from the guy he'd just testified against. Gaither was brutally tortured and killed. His family sued and initially won $168,000, but the judgment was vacated on appeal, with judges ruling that officers could not be held accountable for Gaither's death because the "execution of the undercover operation was left to the judgment and discretion of the detectives." The Kentucky Supreme Court overruled the appeals court in 2014, nearly 20 years after Gaither's death.

• In 2007, a small-time southwestern Washington drug dealer agreed to help police nab a heroin dealer to get out from under drug charges of his own. Jeremy McLean, 26, did multiple drug buys while police listened through a wire. On New Year's Eve 2008, his body was found in the Columbia River with four shots to the head. He'd set up a local heroin dealer, William Vance Reagan Jr., who confessed to killing McLean while he was out on bond. His family later settled a lawsuit for $375,000.

• In 2008, 23-year-old Rachel Hoffman was killed in Perry, Florida, when she lost contact with officers in the middle of a controlled buy for two and a half ounces of cocaine, 1,500 Ecstasy pills and a handgun. The convicted felons she met with found the wire in her purse. Her body was found two days later, shot five times with the gun police told her to buy.

In the wake of Hoffman's death, state legislators passed Rachel's Law, which placed restrictions on how police use informants. The law demands training for police, and among other provisions gives them a list of specifications to consider, including age, maturity, history of drug abuse, risk to the informant, criminal history and emotional well-being. The law also now requires police in Florida to maintain an up-to-date database of confidential informants.

• Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Justice inspector general found that the DEA paid its informants millions of dollars even after they lied in court. In one example, the DEA paid a "deactivated" informant, who lied in sworn testimony, more than $469,000 in cases spread over 13 offices for five years. The report says the DEA supplied the Justice Department with shoddy data, and could not say exactly how much informants were paid after they'd been discredited. But the report indicates at least $9.4 million was paid to more than 800 informants after they'd been "deactivated." — MITCH RYALS

WHAT'S YOUR POLICY?

The Idaho State Police will not release its budget for the confidential informant program, nor the section of its policy manual that tells detectives how to handle secret sources. In fact, ISP doesn't even maintain a record of the money it spends on confidential informants, or on drug investigations overall, according to a response to an Inlander request for public records. The Kootenai County Sheriff's Office, by comparison, doesn't have a policy governing how informants are used, according to their response to a public records request.

"The fact that police won't even release their policies is a quintessential aspect of that culture of secrecy," says Alexandra Natapoff, a professor at Loyola Law School and one of the nation's leading experts on confidential informants. "That a police department feels entitled to withhold that information even after someone has died seems to be contrary to public policy."

ISP's refusal stands in stark opposition to local and state law enforcement agencies in Washington state. The Spokane Police Department's full policy manual, including the section on confidential informants, is posted on their website. The Spokane County Sheriff's Office and the Washington State Patrol readily emailed copies of their policy manuals to the Inlander. WSP's response even included a redacted copy of a contract between an informant and a detective, documents that show specifically what information about informants the police keep track of and how payments are approved and tracked.

The Inlander did, however, speak with ISP investigators generally about informant use:

Although Idaho State Police policy allows detectives to use juveniles as informants, Sgt. Michael Van Leuven says it's rare and would require consent from a parent or guardian. The most common use of people under 18, Van Leuven says, is for alcohol sales control: "We'll have them go in and try to buy booze."

Van Leuven says detectives are told not to push informants to buy more drugs than they otherwise would.

"If we have an informant that says they've been buying grams from someone, we're not going to ask them to buy ounces," he says. "I think that would be improper, unprofessional and unethical. We don't want to make you into something that gives you a much longer prison sentence by doing something you wouldn't normally have done."

— MITCH RYALS