Henry James Warre grew up with the kind of military pedigree that could take a young man far in the British Empire of the 19th century. He was born in the colonial outpost of South Africa and educated at Sandhurst, England's premier officer-training academy; his family even pronounced their last name with a short "a," as in war. While still a boy, he traveled across Europe and saw how rival countries managed their troops. In 1845, when he was 26 years old, the new lieutenant sailed across the Atlantic as aide-de-camp to Sir Richard Jackson, commander-in-chief of all the forces in British North America. Even though Jackson happened to be Warre's uncle by marriage, it was a position reserved for the most promising of young officers.

Lieutenant Warre's appointment coincided with a time of crucial importance to the Pacific Northwest. Since 1818, England and the United States had shared the region under a policy of joint occupation. Now U.S. immigration along the Oregon Trail was growing at an explosive rate, and the sensitive boundary issue had to be resolved. Many British politicians thought that their country had a legitimate claim to all of what is now Washington, the Idaho Panhandle and northwestern Montana. In the United States, James K. Polk had just been elected president under the campaign slogan "54" 40' or Fight!" pushing for a boundary line that would have effectively pushed Canada far to the north. Diplomatic relations were decidedly strained. The British government was in need of unbiased information, and Warre's experience in both diplomatic circles and military service made him a perfect choice for a mission of espionage.

Getting River Legs

In early 1845, General Jackson appointed Lieutenants H.J. Warre and Mervin Vavasour, a 24-year old Royal Engineer, to conduct a secret military reconnaissance while posing as "private travelers seeking amusement." Special orders called for the pair to accompany a Hudson's Bay Company fur brigade across the continent to the Columbia District. Along the way, they would play the role of sportsmen — hunting and fishing, observing all manner of natural history, and seeking spots of scenic interest. But their real mission was to assess the British hold on the Pacific Northwest. The sapper Vavasour would draw plans of all the fur trade posts south of the 49th parallel and propose recommendations on ways to fortify their positions. The more genteel Warre, in addition to keeping copious journal notes, would make drawings and watercolors so that decision-makers in England might see in more detail the places and people whose nationality they were about to decide.

The well-dressed pair of young sportsmen embarked from Montreal on May 5, with a fur brigade under the command of Peter Skene Ogden, who had worked in the Columbia District for years, leading several expeditions from Fort Walla Walla into the Snake River Country. Ogden's charge was to lead Warre and Vavasour safely across the continent and help them claim British ownership of Cape Disappointment at the mouth of the Columbia.

Making standard brigade speed, which wilted many a civilian traveler, they reached Fort Garry at the Red River colony on the site of modern Winnipeg by early June. Initially terrified of the relentlessly fast water, Warre still displayed a certain fascination with the birch-bark canoes, noting their clever construction, wonderful elasticity, and the way that the native design was "admirably suited for the intricacies of the Navigation." As he settled into the journey, Warre focused on the bow paddler, a mixed-blood Iroquois named Baptiste. With a simple pencil sketch, he captured the rugged cool of the paddler, and in his diary he described Baptiste's duties:

He is constantly on the look out for sunken rocks; or dangerous snags; invisible to the Stearsman, whose duty is to follow exactly the motions of the Bowsman, and to assist in navigating the frail bark, through the numberous dangers, arising from Falls & Rapids—Sunken Trees or Rocks—Sands & Shoals. The steadiness & coolness of the Bowsman & the dexterity & attention of the Stearsman, convinced us at length, by the apparent facility with which they avoided the dangers, that our fears were needless; & we soon acquired sufficient confidence to admire the perseverance of the Voyageurs; & the coolness & intrepidity of the guides.

From Red River, Warre and Vavasour sent their first official report. They enumerated American ships and fortifications along Lake Superior, emphasized the impracticality of moving any large numbers of troops and supplies along the arduous route they had traveled so far, and assured their commanders that "perfect secrecy as to our destination has been maintained."

Warre's journal for this first leg of the trip bristles with the stiff arrogance of an educated English officer who was very much a man of his time, especially when dealing with the voyageurs who were making his journey possible. Ogden, a roly-poly veteran of 35 years in the fur trade, had little patience for the two young lieutenants. "I had certainly two most disagreeable companions," he later wrote, noting the officers' "constant grumbling and complaining" about trail food and several other matters. This might have been expected of two men whose baggage on the lower Columbia included fine beaver hats, frock coats, tweed pants, tooth and hair brushes, and extract of roses.

Over the Divide

While six voyageurs rowed Ogden up the Saskatchewan River in a sturdy York boat, the "sportsmen" followed overland with a Cree guide, two riding horses and a pack horse each. Within another four weeks they were at Fort Edmonton, which Warre admired as the best-built and most orderly of the posts they had visited so far. In early July they departed with 60 horses, making for the much-anticipated pass across the Rocky Mountains. At first sight, Warre sniffed at the great range: "Had I not seen Switzerland I should have been much more struck, but I had allowed my imagination too much scope & as is frequently the case, I was on the whole disappointed."

After the brigade crossed the Bow River and began to ascend the foothills, they walked into a pall of smoke from an enormous forest fire. Warre saw signs of mountain sheep and goats, but the noise of men and horses scared most animals away, and the party's fast pace made him reluctant to go out with the hunters or on his own. He complained that the only game they saw in those wild foothills consisted of ducks, partridges and a porcupine. When they stopped at a stream to breakfast on fresh moose, however, the lieutenant spotted another quarry. "The stream was full of large trout and I got out my fishing tackle and we soon added a couple dozen fine trout, varying in size from 1 to 3 lbs., to our sumptuous feast."

Ogden and his guide led the party over Whitehead Pass, south of the usual routes across the Continental Divide, and cut the upper Kootenai River on the West Slope of the Rockies. From there they made a miserable descent through a burn scar, where "trees [were] fallen in every direction and the black burnt stumps covered us with ashes. I never saw such a Labyrinth." After scaling another mountain pass, their guide led them down to the Columbia River near modern Radium Hot Springs, then south to the river's source lakes. In the Columbia Valley, Warre saw abundant evidence of moose, deer, bears and sheep, as well as huge white firs, ponderosa pines and cedars up to twenty feet in circumference. Hot weather had turned the grass brown, but he delighted in his first experience with bunchgrass: "this herbage growing in tufts & constantly throwing out fresh shoots affords excellent nourishment for the horses."

On August 1, Ogden's party made the short Canal Flats portage and rejoined the Kootenai River, where they found the water running like a sluice and travel very difficult. A season of late, extremely high runoff turned them west at the St. Mary's River, near modern Fort Steele. They crossed a divide, hooked up with the Moyie River, and within a few days were looking down at Kootenay Lake near Creston, British Columbia — as Warre described it, "a very extensive Lake or rather swamp called Flat Bow Lake." After a mosquito-plagued night, the furmen came upon a Kootenai camp at the river crossing:

They were very friendly & civil conveying us and our baggage over the broad swift current in their light Canoes made of Pine Bark, and very peculiarly constructed,with the stems & bows running to a point near the Water. We breakfasted on the opposite shore & were visited by members of the tribe all of whom Men Women & Children went though the Ceremony of shaking hands.

Meeting DeSmet

From Kootenay Lake, the furmen headed upstream on the Kootenai River to the location of modern Bonners Ferry, then crossed a small divide and came down along the Pack River. At noon on August 12, they came to Pend Oreille Lake. As they contemplated another wet river crossing, they were approached by a fur party that included the Jesuit priest Father Pierre DeSmet. DeSmet had left Fort Colvile a week earlier, inspected the progress on his new St. Francis Regis Mission to the Crees in the Colville Valley at Chewelah, visited his St. Ignatius Mission on the site of the present Kalispel Reservation, and was moving on to the Kootenais. Warre was impressed to learn that the devoted missionary, formerly a very wealthy man in Belgium, had generously endowed an entire college in St. Louis. The two men compared their drawings of local Indians, and DeSmet put to rest many rumors and exaggerations Warre had heard about the Columbia country. In all, the lieutenant asserted, "He is the most intelligent Man I have met with in the Country & amp; with fewer prejudices."

For his part, Father DeSmet convinced Warre to deliver a packet of his correspondence downriver for conveyance to America and Europe, and also gleaned all of the salient details of Warre's and Vavasour's secret mission. "It was neither curiosity nor pleasure that induced these two officers to cross so many desolate regions and hasten their course towards the mouth of the Columbia," DeSmet wrote. "They were invested with orders from their government to take possession of Cape Disappointment, to hoist the English standard, and erect a fortress for the purpose of securing the entrance of the river in case of war."

At the outlet of the Pend Oreille River from the lake, just below modern Sandpoint, Ogden's men retrieved a cached bateau. They stuffed it with the officers' baggage and began an easy trip downstream, "sending the horses light, by the banks to relieve their weary backs." The river ran deep and clear, and over the next two days their only portage was around Albeni Falls, which Warre pronounced very pretty. During the float they met numerous Kalispel Indians fishing and shooting from their sturgeon-nosed canoes. The furmen stopped to talk with a large party of Kalispels who were on their way to the prairies beyond the Rocky Mountains, where they intended to pass the winter hunting buffalo.

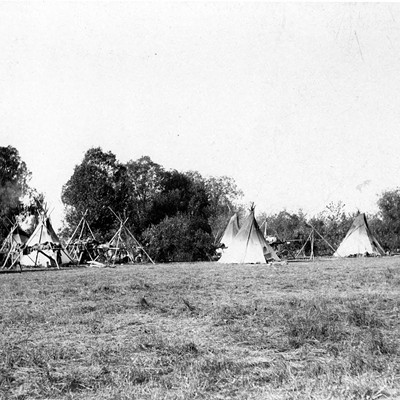

On August 14, probably near Usk, the fur brigade reached the point where they were to strike across the mountains to Fort Colvile. Kalispels who met them at the traverse were civil, but after discovering that the furmen were out of tobacco did not seem inclined to help with their baggage. Here Warre noted what he called the tribe's "only peculiarity... the manner of building their huts some of which were raised by large stakes a considerable distance off the Ground & thatched with a kind of long reed — very picturesque." In an accompanying watercolor, the lieutenant depicted an encampment consisting of several pole structures, each one of unique design, roofed with neat mats of sewn rushes. Two of the houses have tidy sleeping lofts that are fully occupied. One of the frames appears to be covered with hide, as are a pair of teepees to the right of the cluster. Three Kalispel canoes—one in the water, one being hauled ashore, and another turned over to reveal its ribbing—dominate the foreground, and to the left furmen appear to be bargaining with tribal members.

Off to Fort Colvile

With Warre anxious to sleep in the civilized confines of Fort Colvile, the brigade took off on their horses across the broad camas prairie that led to the Flowery Trail road just north of Calispel Lake. At first the trip was enlivened by "Indians Galloping about in every direction and by a large number of horses preceding us to the Fort," but it soon settled into a difficult ascent of five-and-a-half hours through fetlock-deep dust mixed with sharp stones. When they finally reached the height of land, Warre reveled in a panoramic view — eastward, back up the Pend Oreille River to the lake; south and westward, beyond wood and water to the vast sandy plain that encompassed "the whole fall of the Columbia country."

Night caught them in the mountains, and the next morning, the horses had wandered so far that they were late getting off. When they descended to the Colville Valley near Chewelah, they found such a vast swamp that they had to hire two local Indians to guide them north. During a halting trip through the valley, Warre tumbled off his mount at several wet spots, and had to walk around the boggiest sections. In late afternoon, the party crossed some tilled land where a freeman and his Salish wife were growing wheat. The travelers reckoned that the grain was ready to harvest, but found the couple in bed with a fever, too ill to work. The lieutenants picked up speed as they approached Fort Colvile, "singing and firing and shouting at all the Indians we met on the road, like Mad Men or Black feet."

That first night, a painful yellowjacket sting put Warre in a bad humor, and he did not find the supper at the fur post much to his taste — "nothing but dried salmon, tho' there are abundance of fresh fish, even our famished appetites could not eat this tough & amp; nauseous esculant." By the next day he was feeling better and more able to observe the geology of Kettle Falls and the great crowd of tribal people camped up and down the river, "taking salmon in baskets and spearing them & amp; it is incredible the numbers they take." Away from the fishery, Warre observed that although the unusually high water had carried off most of the post's grain crop, horses and cattle were still abundant around the farm, and he saw "several swine lounging about in all their dirty independence."

Unfortunately, no illustrations of the salmon fishery or tribal camps appear among the lieutenants' sketches. Instead, Warre rendered the post buildings, stockade and surrounding hills, while Mervin Vavasour drew a measured footprint of the buildings as well as a landscape elevation to the river, complete with a delicate blue watercolor wash. During low water time on Lake Roosevelt it is easy to match Warre's setting with the original Fort Colvile site in the drowned flat north of Saint Paul's Mission. The sketch shows a skirting of pleasant green deciduous trees along the base of the dry hills above the site, which stick out as a fantasy addition to a place that receives only 12 inches of rain a year.

Down the Mighty Columbia

Within two days the officers were whisking down the main stem of the Columbia in one of the sturdy cedar bateaus that served the Columbia trade. They roared past the Grand Rapids between Kettle Falls and the mouth of the Spokane, and continued on "at a great pace" as the pine forest metamorphosed into the sage and bunchgrass coulees of the Columbia Basin. They camped at another tribal fishery, and when Lieutenant Warre saw the "thousands of salmon jumping and playing about in the water," he regretted his lack of initiative at Fort Colvile, "when I had plenty of time & amp; opportunity to attempt taking them with a fly. Although I was told it would be useless, as Salmon in this Country never could be persuaded to take bait of any kind."

Barely a week later, the two secret agents sent off a dispatch from the Hudson Bay Company's post at Fort Vancouver (across from modern Portland). In this and succeeding reports, they complained about the lawless nature of many of the American settlers in the Willamette Valley. They fretted that HBC traders John MacLoughlin and James Douglas were being far too kind and unsuspicious as to the Americans' expansionist intentions. They disparaged Sir George Simpson for thinking that regular army troops could possibly follow the fur trade routes with any efficiency if war were to break out.

While Warre and Vavasour played the role of tourists and enjoyed the hospitality at Fort Vancouver, Ogden boated to the mouth of the Columbia, where he found that Cape Disappointment was occupied by an American. Ogden immediately offered to purchase the property, but considered the asking price too high. Meanwhile, Warre and Vavasour traveled north up the Cowlitz River to Fort Nisqually, then boated across Puget Sound to visit Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island. Keeping up their ruse, they returned to the Columbia to winter at Fort Vancouver. There Warre painted watercolors of the post and the American village at Willamette Falls. The arrival of H.M.S. Modeste at the end of November brought new energy to the social scene at the fort, and Warre apparently relished the company of the British naval officers. Ogden, however, felt that the young lieutenant was too self-important, especially when he bragged about how much his uncle paid his cook.

In mid-February of 1846, Ogden finally succeeded in purchasing the parcel of land atop Cape Disappointment, and Warre and Vavasour boated downriver for a look at the strategic site. Vavasour scouted gun emplacements for Cape Disappointment and Tongue Point that would control the Columbia should the political situation devolve into a shooting war. Surveying the situation, the lieutenants concluded that the area south of the Columbia would be hard to defend.

Drawing the Line

In March, the lieutenants departed Fort Vancouver with the spring fur brigade. Keeping to their cover, they detoured from Fort Walla Walla overland to Palouse Falls, where Warre humbly set up his easel.

The grandeur of the scene is indescribable, but very beautiful - the numerous rainbows & curious pointed basaltic Rocks the spray & the noise & the wildness of the boundless barren prairie above are such as can hardly be conveyed in the rapid & imperfect sketch I made at the time.

They crossed the Spokane River on April 8, 1846, and paid a brief visit to the American Methodist Mission of Elkanah Walker and Cushing Eells. Celebrating the return of trees, they strolled up the Colville Valley with a large band of free trappers who were bringing their furs from the Flathead country. As the serviceberry bloomed, they embarked from Kettle Falls. The bateaus struggled around the Little Dalles, then the mouths of the Pend Oreille and Kootenai Rivers. Their trip through calm Arrow Lake was "enlivened by numbers of the small peculiarly shaped Indian canoes, which were accompanying us to Boat Encampment, where they intend to remain to make their Summers hunt." The dangers of Dalles de Morts, near modern Revelstoke, and the beauties of Boat Encampment, now drowned behind Mica Dam, put Warre into a state of awed disbelief.

The switch to snowshoes for the ascent of Athabasca Pass left him no time for such reveries.

Woe to the unfortunate, who unaccustomed to these appurtances happens to stumble & fall — It is truly ridiculous to witness the vain efforts to recover the use of your legs & very provoking, the more you plunge the deeper you sink, and at length when nearly exhausted you are again put on your legs by some friendly aid and resume your weary way, dragging the Shoe through the wet Snow, catching every little twig in the net work on which the foot rests, and muttering curses both loud & deep.

The snow was so soft that the voyageurs, humping their 90-pound packs, could make no more than 15 miles a day, and the brigade was running very low on food as they approached the pass. Then, wonder of wonders, they heard the tinkling of sleigh bells. Their old friend Father Pierre DeSmet was just cresting the pass on dog sleds driven by his energetic Cree entourage. DeSmet shared some of his food with the famished voyageurs, and loaned horses to Warre and Vavasour so they could high-tail it to Jasper House. In mid-June, they paused at Red River to pen their final reports, unaware that the Oregon Boundary Treaty was being signed at that very moment. Their conclusions generally agreed with the compromise worked out between the countries that allowed the boundary to follow the 49th parallel to the Georgia Strait, then dip south to leave all of Vancouver Island in Canada.

Upon his return to London, Warre was promoted to captain and continued in military service, participating in the Crimean War in the Ukraine. He never gave up his sidelight as a painter, and his second book of artwork, Sketches in the Crimea, was published in 1855. He served with distinction in New Zealand during the 1860s, and was promoted to major general in 1870. Warre came out of retirement for the Afghan War of 1878, in which he served as commander in chief of British forces in Bombay. General Henry James Warre died in London in 1898.

Although the secret mission that launched such an illustrious military career had little impact on the final boundary decision that made Washington and Idaho part of the U.S., Warre's journal and sketches make an important contribution to Northwest history. While not a portrait painter who took the time to capture a person's face in close detail — often the figures in his landscapes are rendered as stick or shadow people — he was an observant artist who happened into the Inland Northwest just before the lines of international politics were etched across it permanently. In his brief journal entries, rough sketches and swiftly rendered watercolors, Warre captured details of country and culture — glimpses of a region on the brink of change.

Jack Nisbet is the author of Sources of the River and Singing Grass, Burning Sage. His next book, Visible Bones, will be published in the fall by Sasquatch Books.