When wildfires rage across the landscape, whether on grasslands or in forests, the massive plumes of smoke that rise into the air and travel for miles can carry more than a thousand different types of microbes with them.

Yet until University of Idaho associate professor Leda Kobziar came along, there was essentially no research on what bacteria and fungi might be carried in that smoke, how far those microbes might travel, or how they might impact soil ecology both where the fire started and where the microbes land.

So Kobziar and a postdoc researcher ended up coining the term pyroaerobiology to describe the brand new field of study around 2018, Kobziar says.

"There was nothing to call it, and really there had only been one paper that had addressed the topic at all in sort of an indirect way in 2004," Kobziar says. "So we were picking up from that idea and just moving forward with it in ways that nobody had done, unfortunately, because it's such an interesting topic."

For the last four years, Kobziar has been the director of U of I's master of natural resources program.

But this year, in addition to ongoing work with the U.S. Forest Service and the Environmental Protection Agency, she'll be able to focus more on microbe research as part of a $940,000 National Science Foundation grant.

The NSF grant will help fund Kobziar, who is based out of U of I's Harbor Center in Coeur d'Alene, and her partners across the country as they study grassland fires in Kansas and in a specialty lab-controlled environment at the U of I Moscow campus.

Specifically, they'll be looking at tall grass prairies, which are some of the most frequently burned landscapes around the world, she says. They'll be looking to learn how fire influences biodiversity, whether microorganisms in smoke live long enough to land somewhere else, whether they can repopulate when they get there, and how they impact the sites where they land.

"Smoke could be acting as a temporary refuge for microorganisms," Kobziar says. "In very large fire circumstances, it could be that it's a very important part of restarting the life cycle. We want to understand how [microorganism] community dynamics change with smoke."

It's also important to understand those things as scientists want to know how crops and plants that depend on microorganisms might be impacted after fires.

Plus, smoke can carry microbes that are dangerous to human health, so some of the research may ultimately illuminate just how concerning wildfire events can be for people.

"Everything we're exploring seems like the real fundamental stuff to understand," Kobziar says. "We know it's been taking place for many millions of years, but it's never been quantified in terms of its importance biologically."

STUDYING SMOKE

Some microbes that help with nitrogen production, for example, are extremely helpful. Some fungi can also be important for symbiotic relationships with plants, she says. But harmful pathogens can also be transported in smoke.

Currently the filters Kobziar's team use to collect smoke samples aren't fine enough or set up properly to analyze viruses, she says. The team uses unmanned drones to collect samples, and filters that could trap viruses would likely be too heavy for that equipment to carry.

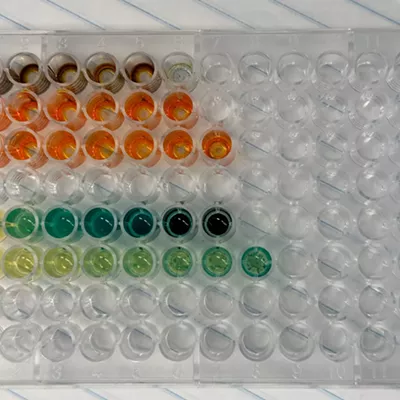

When possible, her team takes air samples before a controlled burn happens, or at a spot very close to a wildfire where smoke hasn't touched that air yet. That shows which microbes are already in the ambient air, which the scientists can then compare to the bacteria and fungi found in smoke samples.

So far they've found more than 1,000 different types of microbes in their smoke samples that aren't found in ambient air, she says.

For this year's NSF grant, Kobziar will work with the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nevada, the University of Florida in Gainesville and San José State University to study fires on tall grass prairies.

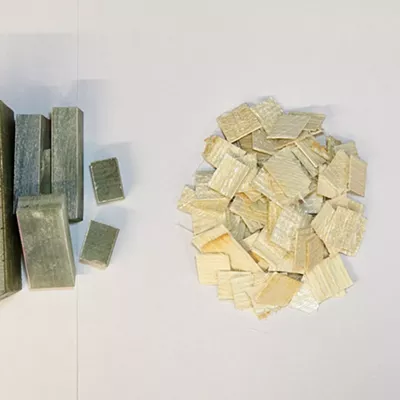

In addition to studying controlled burns that happen every few years in Kansas, Kobziar's team will be able to take soil and grass samples from a site there and experiment inside a combustion lab on the Moscow campus.

"We'll do some smoke experiments where we directly take soils that are sterilized and expose them to known quantities of smoke-produced organisms and see what happens," Kobziar says. "We'll see if these organisms have the capacity to reproduce wherever they land."

Researchers at San José State University will also create models to predict how far microbes could potentially travel in wildfire smoke as part of the project.

While the NSF work is ongoing, Kobziar is also working with the EPA to sample wildfire smoke whenever conditions allow for that.

"Whenever those happen, we take advantage of those either on the ground or with drones if we can gain access to them," she says.

Because unmanned drones are always a lower priority than the safety of firefighters and manned firefighting aircraft, it's not always possible to get samples in the air at wildfire sites, she says. At times it's still possible to get samples from the ground depending on the flow of the smoke.

However, some of her students in the master of natural science program are also wildland firefighters, and as more of them become interested in her work, there may be more chances to partner with Forest Service drones that are already used to survey the perimeters of wildfires.

"But we also ensure our sampling is done using aseptic techniques from start to finish," Kobziar says. "Everybody handling equipment has to be using gloves that are sterilized ... that kind of makes having anyone else do it complicated."

One of the most pressing questions facing her field is how these microbes might impact human health. We already know that exposure to smoke can be damaging to human health. But how might microbes, especially allergens or pathogens, play a role?

"It's imperative that we understand that, especially given that we live in a fire environment," Kobziar says. "We have to accept the fire regime as being part of our environment. It's something we need to live with."

As research reveals more information about harmful allergens in smoke, health officials could potentially have more of a heads-up about situations that could impact people who are immunocompromised, she says. Alternatively, more information could alleviate some concerns.

Another fascinating question Kobziar is curious about: What happens when there are fires in areas once covered by permafrost, where soils that have been buried under ice for millenia are now becoming exposed?

"What that might mean for new microbes or microbes that haven't been there for thousands of years?" Kobziar asks.

Many other questions remain to be explored, too.

"I used to laugh about this being a lifetime's worth of work," she says, "and now I realize it's more than that." ♦