Imagine the perfect goat. And yes, let's acknowledge that contemporary beauty standards for goats may vary depending on the culture. But generally, go with us here.

A perfect goat grows up fast. A perfect goat resists disease. A perfect goat generates muscle mass efficiently. A perfect goat doesn't take as much food, water or antibiotics to get ready to be slaughtered for food.

Everyone wants to breed a perfect goat to breed almost-perfect kids. Just one great male goat can transform a whole herd. The problem is that there's not a lot of good goats to go around.

But in Pullman, there are a few perfect — or at least pretty great — goats bleating in their pens at the goat barn at Washington State University as researcher Jon Oatley explains the revolutionary innovations these goats have unlocked.

What WSU did was to figure out a way to effectively snag a perfect goat's genes, and hack the DNA of another male goat so that it too fathers another perfect kid.

"We can take that one male, and we can essentially carbon-copy him 100 to 1,000 fold," Oatley says.

To be clear, it's not a clone. Clones are expensive, and riddled with the DNA problems that come from "all the crazy things you were exposed to in adulthood," Oatley says. It's better than a clone.

Effectively, WSU extracts the genetic code from one elite goat and cuts and pastes it into a ton of other goats, forcing those goats to produce the offspring of the elite goat.

"We go into his testicles, and pull out the sperm-producing stem cells," Oatley says.

Then they transfer the stem cells of the elite goat and inject it into the testicles of another goat. And if that other goat is a normal goat, well, nothing happens; a normal goat already makes its own run-of-the-mill hoh-hum goat sperm.

"Those micro environments are already occupied. If we introduce new cells, they don't have anywhere to go," Oatley says. "So we have to get rid of the ones that are already there in order to introduce new ones."

That's where the really fancy science comes in.

"We have to make these surrogate males that don't make their own sperm," Oatley says.

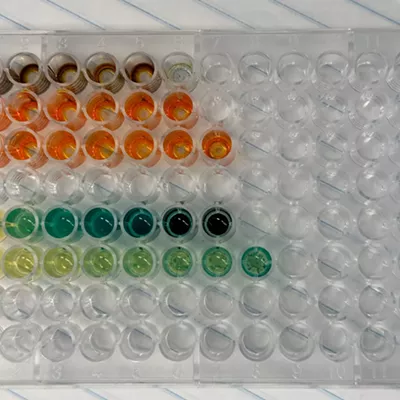

WSU figured out the exact string of genetic code that allows a goat to produce sperm. By using a genetic editing tool called CRISPR, they're able to knock out the section of code in the single cell of a goat embryo. That embryo grows into a goat that's unable to produce sperm.

"They have testicles, just like a normal animal," Oatley says. "But they just lack the cells that make sperm."

Inject the elite goat sperm stem cells into the spermless goats, and the stem cells automatically graft into the missing space.

"We try to do it as early after birth as possible, so that the introducing-donor's stem cell is growing up with the animal as it matures," Oatley says.

By the time it matures, the goat starts pumping out sperm containing the elite goat's DNA sperm. Theoretically, a goat in Asia could start producing offspring with the genetic material of an elite goat that's never left the shores of the United States.

And there's another benefit: Knock out the sperm genes in both female chromosomes and just one male chromosome, and through the magic of genetics, start creating a unique line of goats. Some of the offspring are spermless surrogate goats, with the empty slot in their genetic code that can be filled by a better goat, while others are able to have kids, but some of their offspring don't produce sperm.

By now, it's not a new technique.

"We've done it with goats, we've done it with pigs, we've done it with cattle, we've done it with mice," Oatley says. Not only is WSU a leader in this technique, nobody else is doing it. Oatley suspects that researchers in other labs haven't figured out which part of the genes eliminates sperm production.

There are many commercial opportunities: They could sell the surrogate goats that produce elite goat children directly. Or they could sell access to the goat breeding program, working with a rancher to create a custom elite goat breeding program.

Eventually, WSU is hoping they could even grow the goat sperm stem cells in a lab.

"You can get those isolated sperm stem cells to amplify by a millionfold," Oatley imagines. "So now we have an abundance of cells that we can then transplant and transfer."

They've done it with cows and pigs, but not yet with goats.

Oatley acknowledges that messing with genetics this way can bring up some genuine ethical questions. But the impacts can be profound, he says.

"We're doing it because we're trying to address food insecurity. Right? How can we get meat to people more effectively?" Oatley says. "How can we address malnourishment, lack of access to food, all these things?"

A goat that can grow faster and take up less food is a goat that is less costly and has less of an impact on the environment. That's particularly important, considering livestock can be a huge contributor to global warming. It could even reduce the controversial use of hormones in livestock.

"The reason that we use hormones is to overcome bad genes," Oatley says. Start with great genes, and hormones are unnecessary.

Of course, there are ways that repeatedly seeding the world with one set of goat DNA could backfire. Without enough genetic diversity, a disease that would otherwise impact just a few goats could become a worldwide livestock pandemic.

It means that WSU has to use its power judiciously, Oatley says. Instead of just copying one ideal goat, they copy dozens. And they would need to track exactly where each line of elite goats is located to make sure there isn't an overabundance of one type or another.

Could, theoretically, this same technology be used with humans? Could we, say, create a whole army of LeBron James-children to make the world's most unstoppable AAU team?

"Can we do CRISPR modifications with humans?" Oatley says. "Yeah, we can. And people have with human embryos, and it causes a lot of controversy."

The big ethical question with genetic modification is about intent. Modifying DNA to cure a genetic disease? That's a pretty good moral justification.

"If it's doing it for performance traits, to make somebody have more muscle mass or be taller, be faster, whatever, that, in my opinion, is unethical," Oatley says. "I tell people that I train in the lab: Just because we can do something doesn't mean we should. I think everybody has their own moral-ethical compass they have to go on." ♦