When the cat’s away, to paraphrase an old cliché, the rats will play.

Neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp, working at Washington State University, has devoted a decade to watching that play. And from those modest observations, he’s made discoveries that could transform the worlds of biology, philosophy and medicine.

The first big epiphany came after more than 10 years of watching rats play together. Two rats tussle and flop around frantically. They seem to be absolutely silent. But now he knows better. They were making sounds like a dog whistle, in a pitch too high for the human ear to hear.

Using the same device used to detect bat sonar, Panksepp modifies the pitch of the rats’ voices, allowing him to listen to what the sounds they’re making. As the rats play together, they spit out a rapid series of chirps.

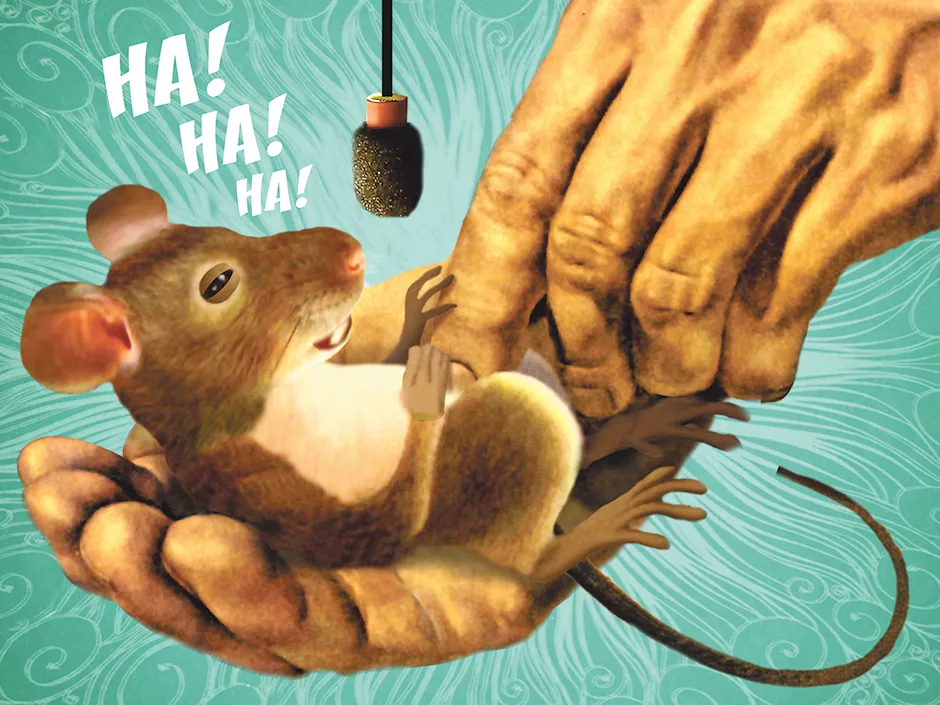

After three years of experiments, he makes another discovery. He tries tickling the rats, just like he would tickle a small furry human. Coochee, coochee, coo.

Suddenly, the chirps get more frequent and frantic. The rat follows around his hand, practically begging to be tickled more. The sounds aren’t quite a chortle, or a snicker or titter or guffaw or anything you’d hear from a sitcom studio audience, but to Panksepp, it’s become increasingly undeniable: The rat is laughing. At least, it has all the characteristics of human laughter.

It doesn’t work on domestic mice — they play differently. But rats play in a physical way, in a way that leads to laughter.

That discovery — that rats laugh — is more than just a fun fact you could picture finding on a Snapple cap. It could even save lives. Two weeks ago, the New York Times reported on a sharp spike in the suicide rate, reporting that suicide has begun to take more lives than car accidents. Depression isn’t just sadness. It’s a public health crisis. Rats, oddly enough, may be illuminating a solution.

As the rats laugh, Panksepp has dug deeper into their minds in the most literal sense. Using deep brain stimulation, he’s mapped the rodents’ brains, showing that their laughter reflects a genuine rush of positive emotion. As with humans, certain parts of the brain light up when they feel good, others when they feel bad. He looks at gene expression patterns — which proteins are being manufactured through the play and laughter — to understand even more. Tickling brings the rats joy. Laughter is an expression of that joy. Neuroscience has begun to, in a sense, reverse-engineer “joy.”

“We’re all mammals,” Panksepp says. And research on rats, he believes, has revealed the sort of primitive mechanisms that are impossible to study in humans.

Because of this sort of exploration, scientists at Northwestern University have isolated a certain polypeptide — four bonded amino acids — with potential to treat depression. “The search for this molecule started 25 years ago,” Panksepp says.

Most medication, like Prozac, is slow to act, and requires frequent dosage. This polypeptide has to be injected — it’s a protein, so if you swallowed it, you’d just digest it like a bite of meat. But early tests in humans have shown that it begins to improve moods within that very day, Panksepp says. And a single injection lasts all week. “We saw no negative effects of any kind. … It significantly reduced depression,” Panksepp says. “The size of the effect was bigger than presently used medication.”

One paper even discusses the possibility that it may be a way to treat autism. You can’t get much closer to “miracle drug” than that.

Just the fact that rats are laughing, that they seem to be displaying genuine emotion, has meaning for one of the most confounding philosophical mysteries: “consciousness.” There’s something — call it a soul, call it a spirit, call it an accidentally self-aware mass of neurons — looking out through your eyes, experiencing your thoughts.

But lately science has been banging at the door of philosophy, showing just how physical consciousness is. And then it follows: If animals experience pain, happiness, sadness, laughter — who’s to say they aren’t conscious as well? Who’s to say, ethicists like Peter Singer argue, that animals aren’t deserving of moral consideration?

“We define consciousness as having internal experiences,” Panksepp says. Now, the evidence says that animals are, indeed, having internal experiences.

Last July, before an audience in Cambridge that included star scientist (and scientist of stars) Stephen Hawking, Panksepp joined with other academics to officially declare that “the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Non-human animals, including all mammals and birds, many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.”

In other words, many animals feel in a surprisingly similar fashion to humans. But with a vast amount of research being based on animal testing, that idea has generated resistance.

“The people doing the nasty stuff to animals don’t want to accept that they’re doing nasty stuff,” Panksepp says. One prominent scientist accused him of falling prey to “anthropomorphism,” giving animals human qualities.

Quite the contrary, he counters. His belief is far better described as “zoomorphism.” Humans, it turns out, have a lot of animal qualities.