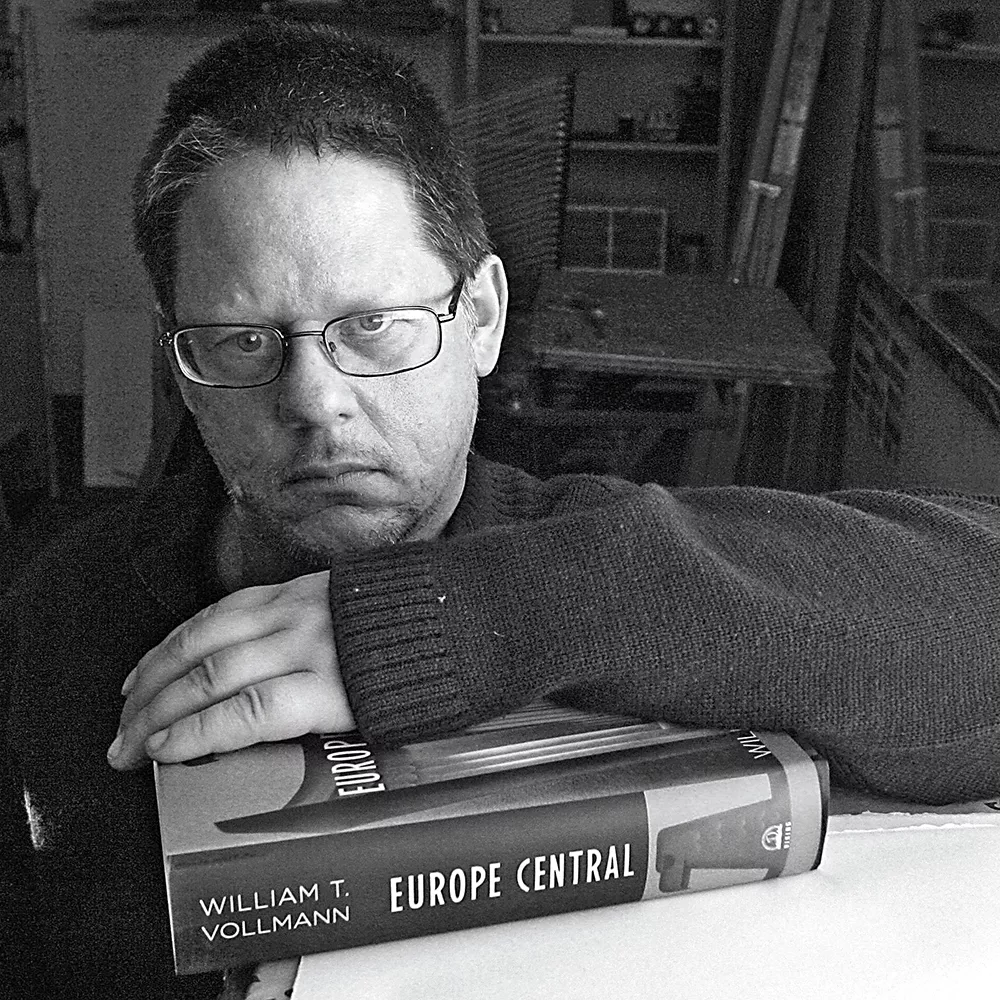

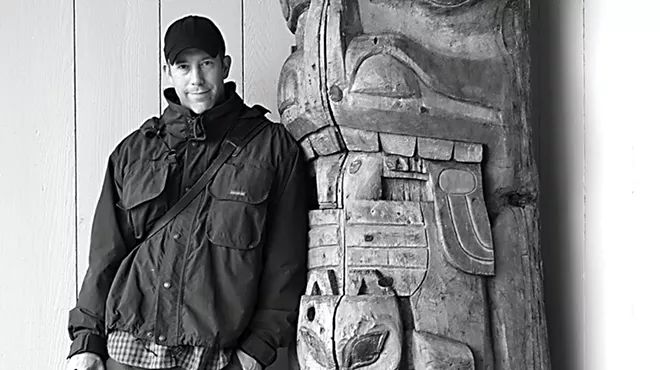

William T. Vollmann has written more than 20 books, both fiction and nonfiction, on a range of topics that include, but are nowhere near limited to, the Inuit, Noh theater, insects, prostitutes and the mujahideen. His seven-volume Rising Up and Rising Down (2003) attempted to establish a moral calculus for violence, and Riding Toward Everywhere (2008) documented his experience as a train-hopper. In a recent essay, "Life as a Terrorist," Vollmann described reading his own heavily redacted FBI file, which indicated that he had been identified as a Unabomber suspect.

INLANDER: It's often noted that violence is a recurring theme in your work. It's noted so often, in fact, that you might question its accuracy. Does it hold true?

Vollmann: Violence is one of the fundamental expressions of human nature. So of course it's a recurring theme in my work, and so is sex, so is love, and so is — a normal, let's say — death. All these things are just human characteristics. My latest bunch of ghost stories, some of them are gruesome, a lot of them are creepy and disturbing; but as Tolstoy said in The Death of Ivan Ilyich, we all come to it in the end. Those people who say that violence is a recurring theme in my work may be right. Because, of course, I'm probably the last person to know my own obsessions.

Discussing Rising Up, Rising Down, you said that violence can be beautiful. You've also said, using a violent simile, that "written words are like bullets that I'm shooting at death." Do those factors work together to make writing an act of violence?

That would probably give writing more power than it has, unfortunately. Literature is something that speaks only to those who want to listen. There are times, maybe, when a writer can change the world in some political way, like Uncle Tom's Cabin or The Jungle, that those books are acts of violence, that they are used by people to mobilize other people to fight this or that. But mostly I think writing is not really an action.

If we trace violence to its root causes in your work, it frequently leads back to power and authority — the abuse of power, the indiscriminate exercise of authority. Would you describe yourself as anti-authoritarian?

Yes, I do, and I'm very proud to say that I do. If you've ever read [America and Americans by John Steinbeck], he said that the average American has a very, very profound distrust of authority. And one of the most frightening things about current American society is that we are being seduced into thinking that we have to have eternal surveillance by institutions — as opposed to by people — for the sake of safety, and therefore we shouldn't be complaining about being spied on and about our liberties being abridged.

Does that have particular resonance for you, given that the FBI pegged you as a Unabomber suspect?

The reality of it is that I wasn't really a victim in this. In a way, as the saying goes, the system works, because I was never arrested, sentenced to prison, tortured, anything like that, as I might have been in some other country. But, you know, my concerns were never about me. I was thinking about what this means for others, and as I said in my article [in Harper's], maybe if my first name were Mohammed instead of Bill, I might not have had the good outcome that I had.

On a lighter note, do you still ride the boxcars, as you documented in Riding Toward Everywhere?

Every now and then, yeah. Actually, when I was in Spokane a few years ago, I was stopped in the yard and cited, and the railroad bull followed me out of there. But, yeah, maybe someday I'll come blowing into Spokane again. Probably not this time [for the Get Lit! festival]. Of course, riding the boxcars is not necessarily a way to save money. If you get a $300 fine, for instance, it's a lot cheaper to have ridden the Greyhound.

You mentioned ghost stories at the outset. That's a forthcoming book?

It's called Last Stories and Other Stories. It's coming out in July.

And why ghost stories?

I started thinking about death a lot after my father died. One of the nice things about a supernatural story is that you can personify some aspect of death. So some of my stories are about the legacies that people receive as a result of death, some are about attempts to cheat death, and some of them are stories about attachment in the Japanese sense. In our culture, ghosts can be sort of frightening, and in this other culture, ghosts are more appealing and sad. It's kind of interesting to mix the two, and as I said, it's almost an infinite subject, so why not write a book about it? ♦

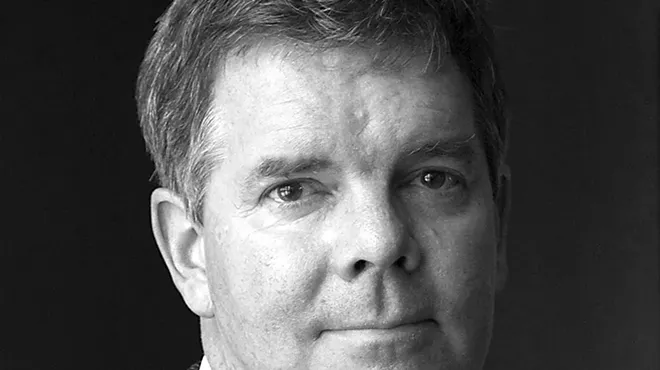

In Conversation with Anthony Doerr and William T. Vollmann • Fri, April 11, 7 pm • $15, students free with ID • Bing Crosby Theater • 901 W. Sprague Avenue