I didn't know it at the time, but on the same day a copy of Hill Williams' book Writing the Northwest: A Reporter Looks Back made it into my hands last week, his family was laying him to rest.

Williams, who died at 91 on March 2, was a journalist and newspaperman in Washington for more than 50 years. He got his start in the Tri-Cities, where he grew up and his father once owned a small paper, before spending most of his career at the Seattle Times.

His third and final book touches on a lifetime and more of Pacific Northwest history, painted alongside the scientific discoveries that shaped his understanding of the area.

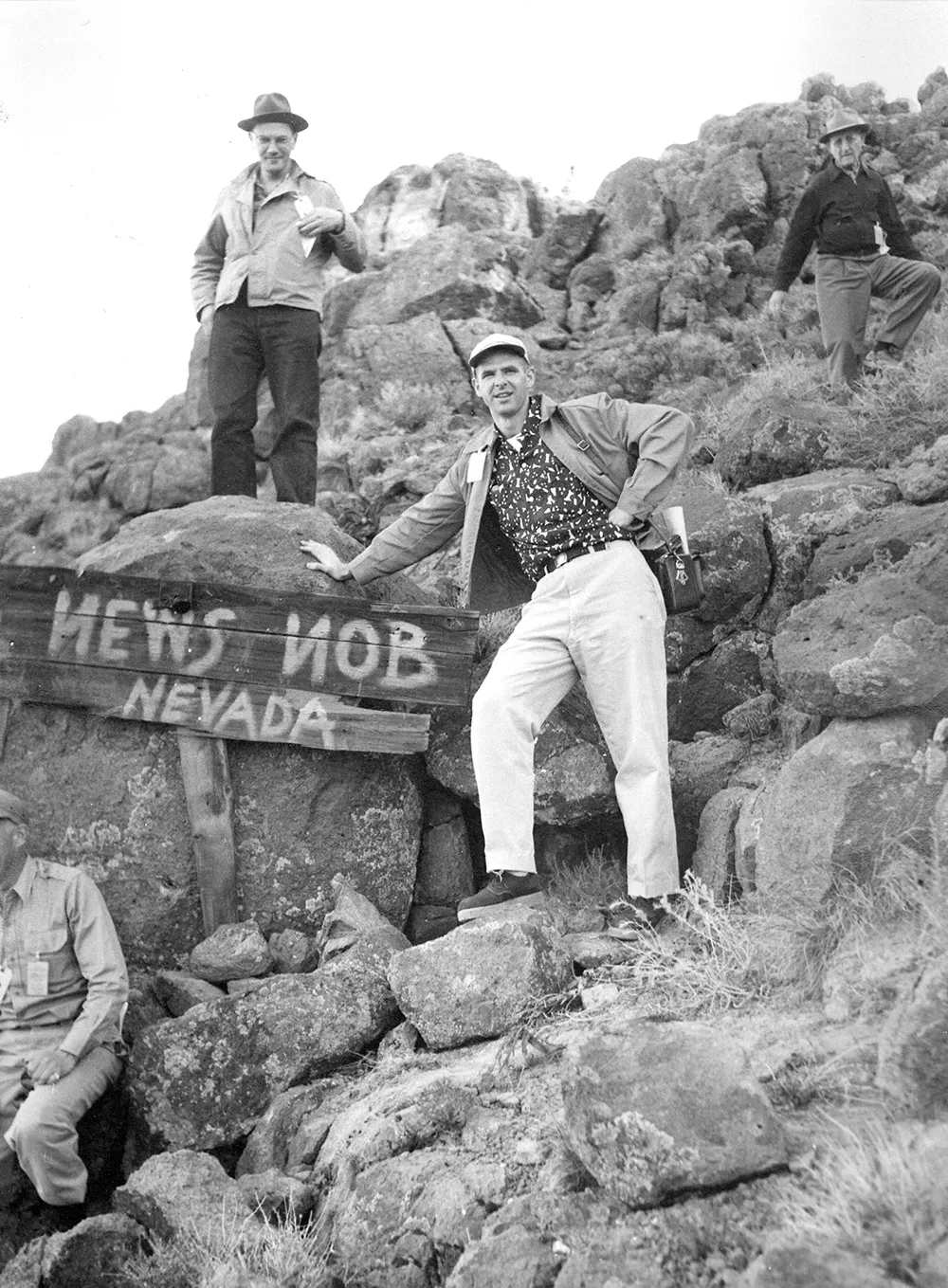

Born in Pasco in 1926, Williams grew up at a time that allowed him to traverse rapids on the Columbia River that William Clark had written about well more than a century before, and later see those same rapids buried under water by the McNary Dam. On assignment for the Tri-City Herald in 1952, he was thrilled to see part of the Oregon Trail from the air as he was on a flight to Nevada to witness an atomic bomb explosion.

"It wasn't until later, after deadlines, that I began to absorb the amazing things I'd seen in just a few days," Williams writes in the book, released in February by WSU Press. "Peering from an airplane that sped more miles in an hour than the wagons traveled in days, I had seen traces of the Oregon Trail, relic of a massive human migration that had populated much of the continent's western coast.

"And I'd seen a light brighter than the sun, a light that changed the world forever, signaling a new era in history."

Williams' book is full of self-aware snapshots like that, giving the reader a glimpse into the many thousands of assignments he had, from riding in submarines to walking the crater of Mount St. Helens, all the while connecting past to present.

As he describes the formation of the Palouse, it's easy to imagine him driving past the same rolling hills I grew up playing in, several decades of crops separating our journeys.

He has a great way of peppering in facts that even locals may not know. Take the time he went to the top of Kamiak Butte, just a few miles from Pullman, with a WSU geology professor who explained, "Where we're standing is the western edge of the ancient North American continent."

The geologist broke open a rock and showed it had a sandy texture inside, likely from the ocean, which at that time started near the Idaho border. New land would have filled in later as the Earth shifted. This was the then-emerging theory of plate tectonics.

Hill started as a general assignment reporter, and later wrote almost exclusively about science, his wife Mary Lou says. She takes my call Sunday afternoon, from the Shoreline home she and Hill built together nearly 58 years ago.

She and their five children heard a lot about Hill's work through conversation at the dinner table, and as he pointed out geologic features from the car on family trips.

"I think I'd have to say science was probably his first love," she says of his writing. "But he really, really liked people too."

One person she says he talked about many times was an elder from Bikini Atoll who had been moved from the tiny islands in the middle of the Pacific, so the U.S. could test atomic bombs there in the 1940s and '50s. Williams visited the area in the '60s and found people still unable to return home.

"He was very empathetic with the people, and you got more than just 'These are the facts, man,'" Mary Lou says. "You got the perspective of the people there, and their longing to get back to their lands."

That applied to scientists and discoverers, too, she says. He was interested not only in their discoveries, but who they were as people.

"As a person he was just totally a straight arrow," she says. "Totally honest, totally truthful, totally dependable, on time, all the good qualities you would hope for. And very charitable and kind; he was always thinking of other people."

Mary Lou says she wishes he could have known how many young men looked up to him as a father or a sort of second father. For many years, he was a Boy Scout troop leader, and taught many how to cook, camp and explore.

"When someone has lived a good life for 91 years, you can't ask for a whole lot more than that," she adds. "I feel so grateful we had all those years together, and he was the influence he was for our children." ♦

Writing the Northwest: A Reporter Looks Back is available through bookstores or direct from WSU Press at 800-354-7360 or wsupress.wsu.edu.