Face it: Kids are gross. And all those snotty and grubby and sneezy kids can easily turn an elementary school into a giant petri dish. A study by NSF International found that a school cafeteria tray had 10 times more bacteria than a toilet seat. And drinking-fountain water spigots had the most bacteria of all — over 2.7 million per square inch.

And this year, there’s another bug to swat: Swine flu (or H1N1, as the labcoats call it). The disease has been relatively quiet in the summer months, though Camp Sweyolokan on Lake Couer d’Alene was shut down after one camper and two staff members came down with the flu — at least one who tested positively for H1N1.

But as students trickle back into tightly packed classrooms, many health experts worry we could see a resurgence. Indeed, the very first H1N1 victim, assistant principal Mitchell Wiener, died after being exposed to infected students at a Queens, N.Y., elementary school. His wife blamed the school for not closing down sooner. His family is suing the city.

So for Spokane-area school districts, the question hangs: What do they do, when the fever strikes?

A lot of that’s up to Joel McCullough, health officer for the Spokane Regional Health District. It’s his finger on the shutdown switch.

Public schools, private schools, alternative schools — any in Spokane County — are subject to McCullough’s orders. But it would take more than a couple sick kids to close the school, he says. And with the current severity of H1N1 thus far, McCullough says he doesn’t anticipate school closures.

Swine flu, McCullough says, isn’t quite as scary as health professionals first feared. “The disease is similar to seasonal flu in terms of severity,” he says. But several things make the illness more problematic. Young populations, like those in school for instance, tend to be especially vulnerable. The elderly, interestingly enough, are more resistant than usual, possibly because they encountered a similar strain of influenza years ago.

But very few people, McCullough says, have immunity. Where the seasonal flu strain only changes slightly year to year — allowing some immunity to carry over — H1N1 is a dramatically different strain.

And influenza, easily mutable, is unpredictable, McCullough says. It’s a disease that can suddenly morph into a much more deadly form.

The Mead School District and Spokane Public Schools both say they’re prepared — and by law, they’re required to be. In 2007, in the midst of worldwide concern over avian flu, or bird flu, the Washington State Legislature passed a law requiring all schools to have pandemic preparations in place. Like many school districts, Mead has developed an eight-page document outlining their response to pandemic flu. During the school year, both districts have monthly meetings with the Spokane Regional Health District to figure out how to combat any upcoming illnesses.

One way is through constant cleaning. Spokane schools don’t want to be like the schools in the NSF International study. Every drinking fountain and every bathroom is cleaned at least once a day with highly rated Sustainable Earth SE-64 disinfectant, says Kathe Reed-McKay, health services director of Spokane Public Schools. Custodial roving crews go from school to school, cleaning from top to bottom.

Another way is through communication. The first week, the school will send parents a letter about swine flu. Periodic updates will follow.

Generally the advice is pretty basic. Make sure kids know to wash their hands, and to use a paper towel to turn off faucet handles. If you’re feeling ill — vomiting, diarrhea, nausea and the like — stay home. Cough into your arm, not into your hand. Keep your bugs to yourself. When the H1N1 vaccine comes out — probably in late September/early October — get the shots. And if you call your kids in sick, give all the grimy, gruesome details, so the school can report it to the health department. Each school catalogs the illness and reports it to the health district. (If more than 10 percent of students are absent, they’re required to report it immediately.)

But not all parents are vigilant. Sick kids still come to school, and schools have to figure out how to separate them. “There has to be a place in the school to send the sick kids,” McCullough says. “We have a prescription pad we can hand out to the schools, that can be sent home to the sick child, under recommendation of the health district.” With that extra oomph from the authorities above, McCullough hopes parents will be convinced to keep their coughing kids home.

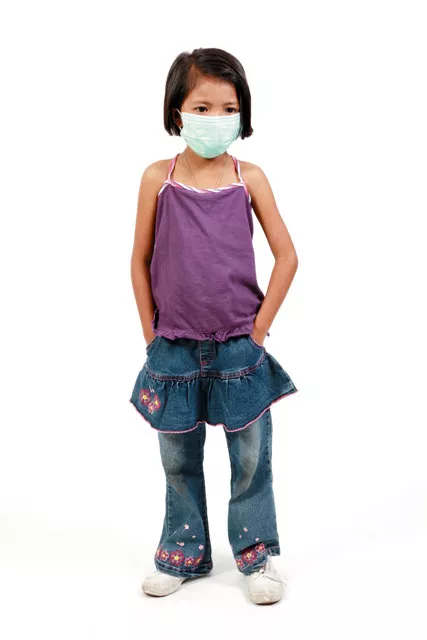

While pictures from India show entire classrooms full of children wearing masks, Reed McKay says, “We’re not at that point yet,” but the occasional mask has been suggested.

“We’ll be discussing the need to have those who are potentially infectious wearing a mask,” Reed-McKay says. “We’ve tried to be reasonable, but still be prepared.”