Melissa Schmitt is in a long-distance relationship. Her husband is serving time for robbery at Monroe Correctional Complex in Western Washington. She, meanwhile, lives outside of Eugene, Oregon. The drive north is roughly six hours, and she doesn't make it up there often.

"Maybe three times a year," Schmitt, 55, tells the Inlander.

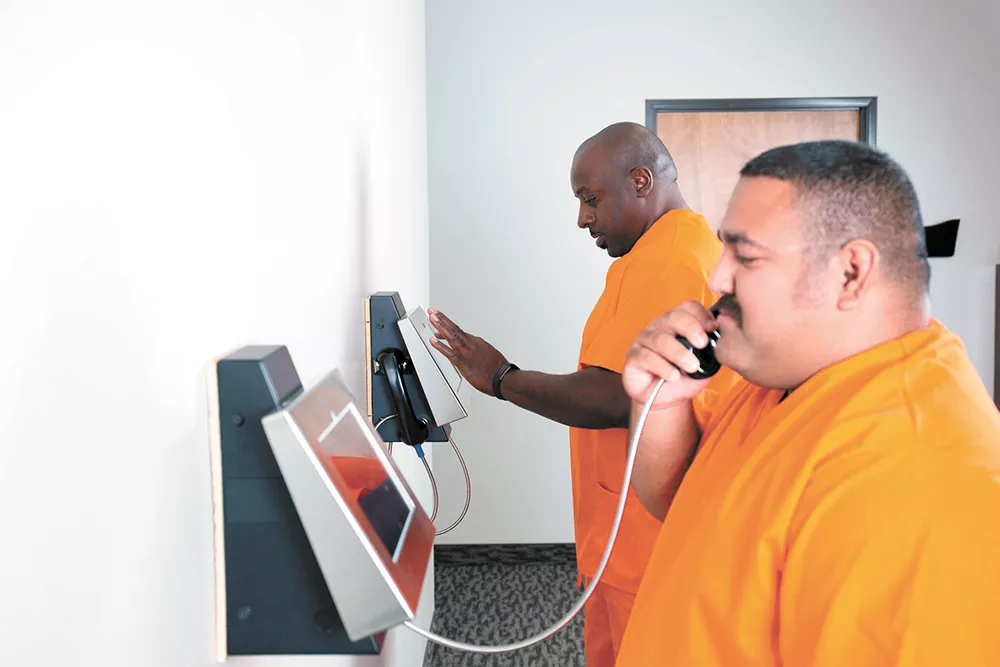

Instead of in-person visits, they rely on phone calls and video chats — basically, a pricey Skype call for inmates — provided by for-profit corporations. But staying in touch comes at a cost: Schmitt says she spends around $200 to $300 every month to pay for calls. (Her husband can't contribute much since he only earns around $1 an hour at his prison kitchen job.)

"We talk every day, usually twice or more, which is quite expensive," she says. "It's awful. It's all monetized."

The notion of taxing inmates and their families for communicating is "criminal," she says, given how crucial family connections are to lowering recidivism rates once inmates are released: "It's an incredible burden on the families, which is really sad."

Local officials, however, are bullish on the idea of video visitations. In early 2019, Spokane County officials put out a request for proposals to replace the jail's current phone system as well as add video visitation. One of the goals of introducing video calls is to "reduce the need for physical visits" at county detention facilities, according to documents obtained by a public records request.

But after the county awarded the contract in late July to Securus Technologies — a major player in the prison telecommunications industry — Global Tel Link, an Idaho-based corporation that bid on the contract, filed a lawsuit against Spokane County, alleging that the bid process was unfair. Meanwhile, the local effort to adopt video visitation technology raises questions about the role of for-profit companies in providing basic services in crowded jails and the monetization of human captivity.

"All too often, private companies step into the corrections space with the hope of squeezing money from poor families for maximum profit," says Wanda Bertram, a spokeswoman for the Prison Policy Initiative, a think tank focusing on criminal justice reform. "The root cause of counties eagerly exploring contracting out services is that populations in jails are so large."

Global Tel Link has provided inmate phone services for Spokane County since 2007, according to court records. Under this arrangement, Global Tel Link made its money from phone call fees, which generally cost around 26 cents a minute, according to Spokane County spokesman Jared Webley. The company gives the county a cut of about $175,000 annually. This money is reportedly spent on "inmate welfare" programming, like education programs and the community garden at Geiger Corrections Center.

Global Tel Link alleges in its lawsuit that Spokane County unfairly deviated from its original methodology for assessing bids for the contract, court records show. County officials, meanwhile, contest that Global Tel Link's bid did not meet their requirements.

Across the board, county officials declined to comment on both the bid process and the county's interest in video visitation, citing the ongoing litigation. Randall Brown, a spokesman for Global Tel Link, also declined to comment.

The county and Securus are currently negotiating the details of the new contract, which will "significantly reduce costs for inmates and their families," Webley writes in an email.

Bertram says that Global Tel Link's lawsuit against Spokane isn't out of character.

"In the prison and jail telecom space, it's relatively common for large players to sue one another or to sue the county that awarded the contract to their competitor," she tells the Inlander. "In many cases, it's a win-win financial strategy for them."

Spokane County's pursuit of video visitation also follows a national trend of state and local correctional agencies adopting the technology. Over 500 facilities in 43 states adopted some form of video visitation, according to a 2015 Prison Policy Initiative Report. (The report also estimates that the technology is more prevalent in county jails than in state prisons.)

"The increase in both the incarceration rate both in jails and prisons has meant that local jails and state prisons are facing capacity constraints," Bertram says. "And under this pressure, with more people being sent to jail, jails are looking at ways to cut costs, particularly staff costs, because one of the most significant line items on a jail's budget is staff."

She adds that, similar to Spokane County's past and future inmate communication services contracts, many jails around the country get a cut of the revenue that firms generate from fees: "That can go into shoring up the jail's budget," Bertram says.

For years, the Bonner County Sheriff's Office has used contracted video visitation services as its only form of visitation at the local jail, which staff say is a major cost saver in terms of human labor. Their contract with Telmate, another correctional communications firm, also doesn't come at any financial cost to the county.

"We're not moving inmates from cell to cell trying to get them to [a] personal visitation," says Ror Lakewold, undersheriff at the Bonner County Sheriff's Office. "Telmate does the installs, they provide all the equipment, all the hardware, and they make their money."

Notably, Securus staff claimed in their bid to Spokane County that their services are "proven to reduce staff workload" and that the county would save an estimated "1,491 man hours monthly" by implementing an automated voice system to provide information to inmates and friends or family using their system.

Spokane County says it wants to maintain in-person visitation despite its interest in video services, stating in a written response to a question from a bidding vendor that the county will "continue to support face to face visitation."

However, Bertram cautions that the introduction of video visitation has regularly resulted in all-out bans on in-person visits. An estimated 74 percent of jails examined by the Prison Policy Initiative banned in-person visits when they implemented video visitation, according to their 2015 report. By banning in-person visits, families have no choice but to pay exorbitant fees to speak with incarcerated loved ones.

"It's frequently used as a preliminary measure and the subsequent measure is that in-person visits go away," she says of jails adopting video visitation.

Research has shown that in-person visits help improve inmate outcomes both inside and outside of correctional institutions. A 2011 study conducted by the Minnesota Department of Corrections found that a single visit decreased inmate recidivism by 13 percent. Other research has shown that parent-child visits improve outcomes for children with incarcerated parents.

Recent studies on video visitation have produced more mixed results, however. A 2017 Vera Institute study on the impacts of video visitation technology in Washington state prisons found that usage rates were low and even those who did cited pricey fees for limiting their use. Many inmates reported frequent technical issues with the system, such as poor audio and visual quality.

"Video calling technology can be a great supplement for in-person visits but they're not a substitute," Bertram says. "They're low quality, they're high-cost, and when they break people can be completely isolated from their loved ones."

Sabrina Ryan-Helton, a staffer with the Bail Project's Spokane branch, tells the Inlander that when she was serving a sentence in a Washington state prison, that video visitation was beneficial for staying in touch with family members who lived far away.

But, ultimately, being able to connect with loved ones in-person is vital for inmates, she says.

"You can draw strength from that," Ryan-Helton says of in-person visits. "It reaffirms your humanity in a place that's really inhumane." ♦