Self-acclaimed literature is nearly impossible to review, due in large part to the nebulous nature of the category. "Literature" is ill-defined, whose boundaries shift for any number of reasons, least among which is whether the first letter is capitalized in normal usage.

On what basis can these books be judged? One possible course of action would be to set Freedom in a ring with Great Expectations and Middlesex to let them duke it out among themselves — but that would just leave us with Free Great Sex, and there’s not a public library in the world that’ll be able to stock that title without a load of grief.

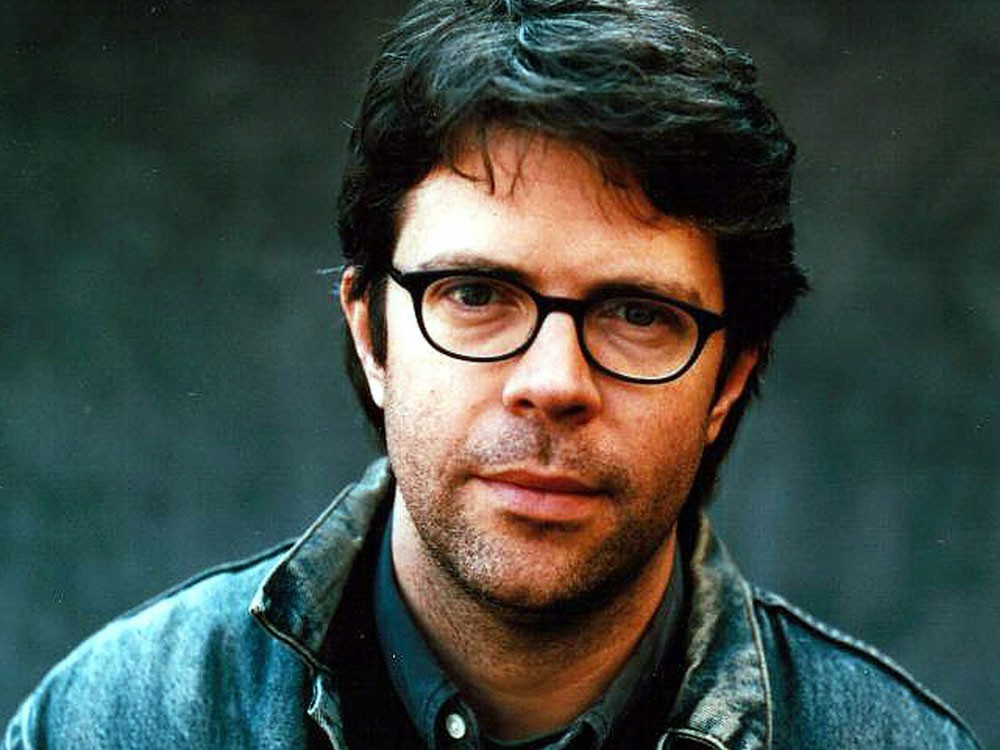

Jonathan Franzen has it let it be known his book is intended to be interred among the ranks of literary fiction, for the high-minded to fawn over now and the teenagers of the future to be bored by later. Setting the intent of this self-aggrandizement aside, readers and reviewers alike must take care to frame the novel appropriately.

To do this, one must look to the title: Freedom. Ultimately, freedom — and, by extension, Freedom — comes down to choices. Difficult choices, no-brainers, impossible choices and choices that are made for you. The title, like with his earlier work (The Corrections) before it, is as much about helping the reader keep the novel's purpose in mind as much as it is to sell more copies. The meandering, often disjointed story can be reined in by making sure the theme is at the forefront of your thoughts. It's especially necessary because freedom is, at its core, a completely empty word. Essentially, it's a stand-in for "limitless choice," aka "everything." And while everything is the opposite of nothing, it's just as amorphous and chaotic a concept.

The plot of Freedom, such as it is, centers around the Berglunds, a Minnesota nuclear family going through more than their share of bewildering circumstances they must face up to or ignore, at their pleasure. It's not really possible to plot the arc of the story, except to say that the main characters seem to be the heads of this particular household, with the husband, Walter, more central to the focus than the wife, Patty. Walter is a man deeply devoted to his wife, who adulates in his attention and loves him in return for it. Their children are quite complicated beings, though Jessica, the oldest, does not appear in the story in any meaningful way until much later.

Joey, the younger son, occupies a much more prominent role both in the story and the lives of the two main characters — fiercely independent (he moves out of the family home before his 17th birthday to live with the neighbors, where his girlfriend happens to reside) while at the same time not entirely comfortable cutting off all ties to his parents. There's infinitely more to the story, but a fear of spoilers and a concern for space prohibit me from even listing all the main characters.

The plot, though somewhat easy to follow, is extraordinarily complex. Like Corrections, the book does not track in a strictly chronological order. This does not hamper comprehensibility too much, but it does require a bit of thinking to keep a finger on when and where various events occur, especially when focus shifts from one character to the next.

The hallmark of the modern Serious Novel can be found in the tribulations — sometimes more bewildering and unlikely than your average episode of The Young and the Restless — its characters must suffer. It's tempting to think the author has confused "voluminous" problems for "interesting" ones, but luckily the book's strength lies more in how the characters react to various outlandish circumstances than the situations themselves.

Of course, to take the mantle of literature a work must shoulder the load of society's burdens, to tackle the big ideas that plague our collective consciousness. 9/11. two wars, disaffected youth, the pretentiousness of disaffected youth, the middle-aged condescension toward the pretentiousness of disaffected youth, the youthful indifference toward the middle-aged condescension ... even selling out, which I'm not 100 percent exists as a concept even in the abstract anymore.

Luckily for him — and for us readers — Franzen doesn't even attempt to provide answers but rather seeks understanding, exploration in lieu of explanation. Part of the reasoning for this is almost certainly pragmatic, as definitive diagnoses and prescriptions can be disagreed with, countered or even dismissed. But part surely must lie, as with all things, in the book, rooted in the central idea of freedom. To proclaim a solution is to inhibit the freedom of the readers to judge and choose, and to provide an answer on our own.

The characters are remarkably fleshed-out and one of the best aspects of Franzen's work. Psychology has replaced metaphor and simile as the literary devices used to drive home a universal truth or compelling point authors want to get across. Where Nathaniel Hawthorne spent an entire chapter crafting a synecdoche about a bush growing next to a prison door, Franzen and other modern writers dig deeply into the motivations, the worries, the fears and the thought processes behind a character's actions. These insights are especially poignant when the characters themselves seem incognizant of their own reasoning; the specificity actually provides more opportunities to interpret rather than limiting possible explanations, as one might expect.

From a prosaic standpoint, there's a noticeable difference from Corrections. Where before a 100-plus-word, single-sentence metaphor might be thrown in to illustrate how the character has trouble forgetting, Freedom saves the run-on sentences for advancing plot — or, failing that, at least fleshing out the scene further.

The writing is not without its flaws, however. A significant portion of the first chunk of the book is a third-person autobiographical portrait of Patty — despite ostensibly being written in her hand, there's not much difference between it and the authorial lugubriousness exhibited by Franzen. It's an uneven bit of writing Franzen rather awkwardly backforms by having other characters praise her writing abilities, but this praise occurs only after we've completed the manuscript — which none of the other characters have read. It’s a bit like if Transformers 3suddenly introduces the fact that Sam is actually half-fish, and for the rest of the movie has the other characters note, “Man, he always was a really good swimmer” despite the entire movie taking place deep in the Sahara. Additionally, double negatives pepper the novel to create a slightly more effete tone to the writing, which is not un-annoying.

As far as recommendations go, Freedom is not going to be for everyone. It can probably be enjoyed passively, eyes jumping from work to word and sentence to sentence, but it's going to be a slog. Instead, if you’re looking for a book to engage with and think about, you'll find a worthy opponent in Freedom. As to its qualifications as literature, few can speak to them with any — meaningful — authority. But then, even when the American Society of People Who Decide What Literature Is (this is not a euphemism for “Oprah”) comes down on one side or the other, you still have the freedom to ignore them and form your own judgment.