As dawn approached,

Hours earlier, after his family took away his stash of pills, Ehlo made a pile of clothes and lit it on fire in a fit of rage, shouting things like "Y'all don't love me!" Before firefighters came, his family held him down, afraid he would jump into the pile as the flames moved closer and closer to the house.

Ehlo wanted to say "sorry" to his wife and kids, but his apology would have to wait. Police were at the hospital, and they took him to jail before he could go home on Aug. 1, 2013. Even after his release the next day, a judge ordered him to stay away from his wife, Jani, two sons, Austin and Gavin, and daughter, Erica.

The day that Ehlo's addiction to painkillers finally overwhelmed him represents a moment of defeat, eclipsing any loss he suffered on the basketball court as a 14-year NBA veteran. That's including The Shot, the infamous one Michael Jordan made over Ehlo that has haunted him ever since.

"I thought just because of my willpower and what I did professionally — fighting through bad ankles and playing through a pulled muscle — that I could just stop taking them," Ehlo says. "And I couldn't."

His addiction is a cruel reality, far too common among professional athletes. Like The Shot, Ehlo knows that the day he lashed out at his family will never go away. He knows no pill will fix it, just like nothing can entirely erase a collapse in defeat. He's simply embraced it all, like he always has, and continued on his never-ending road to recovery.

NO GLORIOUS ENDING

It's lunchtime on a day late last month, and Ehlo's back stiffens as he waits for his food, though his weathered face reveals no pain. His back doesn't hurt as much as it used to, but he admits that sitting still for too long makes things worse.

"The medicine always took care of that," Ehlo says, as he sips a Coke.

Due in large part to his back problems, Ehlo, 54, is not as agile as he used to be. But that's a high standard to go by. Growing up in Lubbock, Texas, Ehlo excelled at all three major sports — football, basketball and baseball. When baseball season ended in June, he'd spend the summer working on his aunt and uncle's cotton farm before picking up the sports cycle again, starting with football in the fall.

His family thought he'd pursue baseball or football. Then he grew. He was skinny, but he had long arms, and he could drive and make 3-pointers. He tried to model his game after former San Antonio Spurs Hall of Famer George Gervin, who had a similar body type.

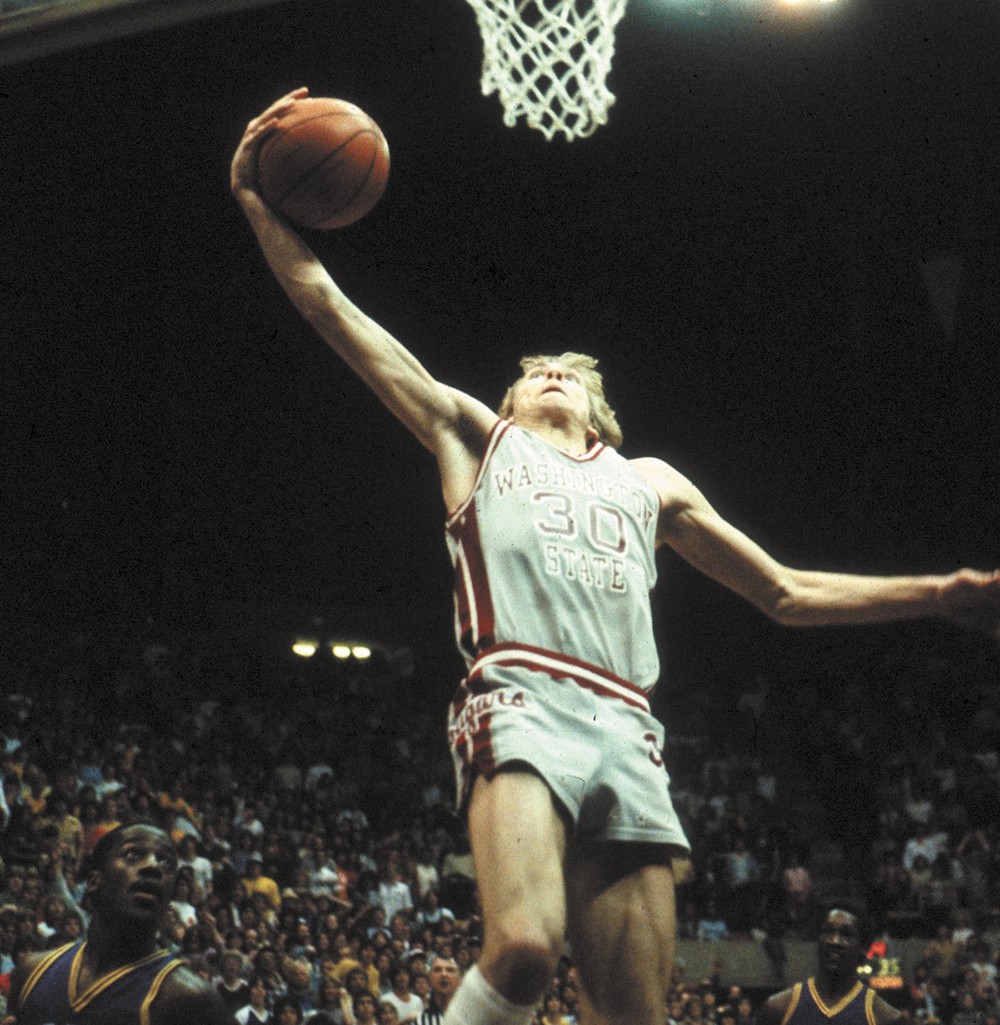

He was playing in junior college when Washington State University coach George Raveling recruited him. Ehlo spent two years at WSU, where he met Jani, and in his senior season helped carry the Cougs to their most wins in a season in more than four decades.

That 1983 WSU team lost to fourth-ranked Virginia in the NCAA tournament's West Regional. Ehlo keeps a newspaper article about the game in a scrapbook. It features a picture of Ehlo face down, his nose buried in the hardwood. The caption begins: "Oh, so close. But for Washington State and Craig Ehlo (who put his nose to the floor), there was no glorious ending Saturday."

Ehlo was selected in the third round of the 1983 NBA draft by the Houston Rockets, where he mostly stayed on the bench. He joined the Cleveland Cavaliers in 1986. In his first two seasons there, he averaged more than 20 minutes a game, and coach Lenny Wilkens often had him guard the other team's best player. In the same division as the Chicago Bulls, that player was often Michael Jordan.

What most people forget is that the Cavs — led by Mark Price, Brad Daugherty, Ron Harper and Larry Nance, all of whom averaged more than 17 points per game in 1988-89 — were considered by some to be the team of the future. Magic Johnson even predicted they would be the team of the '90s. The third-seeded Cavs were confident they could beat the sixth-seeded Bulls in the first round of the 1989 playoffs after winning all six matchups in the regular season. By the decisive Game 5 in Cleveland, with the series tied 2-2, it was a dogfight, and Ehlo was right in the middle of it.

Ehlo was having the game of his life. He finished with 24 points, far above his season average of seven per game. His layup with three seconds left was the reason the Cavs were up 100-99 on the Bulls in the first place.

But three seconds was all Jordan needed. Ehlo and Nance tried to double him on the inbound pass so Jordan wouldn't get the ball, but Jordan was going to get the ball. He caught Ehlo off-balance, dribbled to the left, rose up, hung in the air, patiently waited for Ehlo's outstretched arm to fly by, and nailed it.

Everything about the moment has been immortalized — from the announcer's call ("A shot on Ehlo, good!"), to Jordan's celebratory fist pumping, to the splash of Ehlo's blond hair as he collapsed to the floor in defeat.

Ehlo says that shot changed everything. It's not that he couldn't bounce back — he had his five best statistical seasons starting the following year, before he went on to play for the Atlanta Hawks and the Seattle SuperSonics. But the Bulls, not the Cavs or anyone else, ended up being the team of the '90s, and Ehlo thinks it was The Shot that flipped the script. After that, they could never get past Jordan.

"I don't think we'd be sitting here [if the shot missed]," Ehlo says. "My team was good enough ... if he would have missed it, I swear we would have hung a couple banners."

By the time he retired in 1997, Ehlo's back started bothering him. He had constant spasms, and he couldn't bend over and touch his toes. The physical pain followed back home to Spokane.

It eventually consumed him.

WINNING AND LOSING

Ehlo, as an NBA athlete, could always withstand a certain amount of pain. What hurt the most was that it started affecting his family. He couldn't go out to the lake with them because his back hurt, and he felt it lock up when he picked up his youngest son, Gavin, and threw him into the water.

He had two back surgeries — in 2003 and 2007 — that didn't alleviate the pain. He says he started taking painkillers sometime around 2008. In 2010, he had surgery to fix a herniated disc. The doctor prescribed him hydrocodone.

In 2011, Eastern Washington University's new basketball coach, Jim Hayford, asked Ehlo to join his staff. The two were friends, and Ehlo, who had been working as a local TV commentator, was excited to get out of broadcasting.

"I loved winning and losing," Ehlo says. "When you broadcast, you don't win or lose. You just go home kind of empty."

He was a player development coach. The players would rib him about The Shot, but they generally got along well with Ehlo, a major reason Hayford hired him in the first place.

"He was an absolutely amazing person, and the first thing you want in a coach is somebody who's a great person around kids," Hayford says.

But coaching took its toll. Practices were at 6 am nearly every day, and working with the players on a daily basis was demanding on his recently repaired back. He says his mind was telling him he could do it, but his body was giving out. He took up to 15 painkillers a day, and continued to isolate himself from his wife and kids.

"Craig is such a joyful person, and he would go through some periods where that just wasn't on him," Hayford says. "In hindsight, now I realize there was probably times where he was having to fight his demons."

Through all that, however, Hayford says Ehlo was most helpful after losses. Hayford never had a losing season as Whitworth's coach, so when the losses piled up at EWU at the beginning, it was hard to stomach. But Ehlo, even to this day, sends Hayford encouraging texts after tough losses.

In July 2013, Ehlo resigned, saying he couldn't help at the level Hayford needed. Hayford says he never mentioned why.

But he soon found out.

A couple of weeks later at Ehlo's home just south of Spokane, in the rolling golden hills off the Palouse Highway, the Ehlo family was preparing for an early flight. The next morning, Aug. 1, 2013, they were going to Las Vegas to celebrate Jani becoming a millionaire through Isagenix, a network marketing company.

Ehlo's bag was packed, but he and Jani were fighting. His family went through it and found his painkillers — hydrocodone pills he bought on the street. This was the last straw.

"They took them," Ehlo says. "And it pissed me off. That was when the behavior was of someone in addiction. Just, the anger... "

He took the suit he packed, doused it with gasoline, and ignited a fire. He took clothes that reminded him of Austin or his daughter Erica, and threw them on the fire too. He wanted to burn everything that reminded him of his family. They called 911, and paramedics brought Ehlo to the hospital.

"I thought after the doctor released me from Sacred Heart I'd go home — probably not go on the trip — but at least say 'I'm sorry.' But (the police) were waiting for me," Ehlo says. "So I never got that chance. They went ahead and went to Vegas, and I spent the night in jail."

MASKING THE PAIN

Like her brother, Carla Ehlo usually stays up late. Around 2 or 3 am Aug. 1, she would have been up watching a movie in her home on the south side of Lubbock. She was awake when got a call from her then 22-year-old nephew, Austin, who sounded upset.

He told her everything about the fight, the fire, the police. Carla booked a flight to Spokane.

While Carla was on her flight, her younger brother Craig sat alone in Spokane County Jail. He wore a yellow jumpsuit, orange socks and no shoes — the jail didn't have any that fit. His thinking at that point was clear: He was done abusing painkillers.

He was released from jail the next day.

Back when Craig got his first NBA contract, Carla says he built their parents a house. He bought Carla a car.

Before August 2013, the last time Carla had seen her brother was when their mom died the year before and Craig flew to Lubbock to be with her. Their dad had died a few years earlier.

In 1992, their older sister died of cancer. The family always was close, but they became closer when times were tough, Carla says, and Craig was always the first one there to help.

"He's just a good person like that," she says. "He just does good things for people all the time."

When Carla got into Spokane, Craig was at his mother-in-law's house, surrounded by friends and family. He looked thinner. Craig had been ordered by the judge not to see his wife or kids, and Carla could see how that wore on him.

"I think that's the hardest thing that he had to deal with, was how to get his kids' confidence back and his wife's confidence back, that he could beat this," Carla says. "He does love his kids and wife very much. They are his life."

Ehlo wanted to get treatment across the country on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The place was called Gosnold Addiction Treatment Center. He heard about it from Chris Herren, a former NBA player who was addicted to heroin and treated at Gosnold.

Carla wanted to go with him, but Craig felt he should do it alone. The two split up at the airport. Carla flew to back Texas, her brother to Massachusetts. They talked every other day for a month over the phone, and each time she heard him he was doing better — "back to the Craig before all this happened."

Ehlo is one of many athletes who have battled opioid addiction. It's common among athletes at every level. In the NFL, more than half of former players have reported using opioids, and 71 percent of those players reported misuse of the drugs, according to a 2011 study funded by ESPN and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Ehlo isn't the only former star athlete from WSU who has experienced such a problem. Ryan Leaf, a former WSU quarterback picked No. 2 overall in the NFL draft — and considered by many the No. 1 overall bust in NFL history — recently spent time in prison for breaking into homes and stealing prescription pills.

"It's a fact that athletes have injuries. It's a fact that athletes have pain. And it's a fact that doctors are there to treat that pain," says Lori McCarthy, Gosnold's director of clinical outreach. "It's really about the person taking the pain medication, and what that means to them, and what gets set off in the brain that will propel someone to continue to use something, even if it's no longer needed."

Ehlo, in fact, has some experience on the other side. Two of his Houston Rockets teammates — Mitchell Wiggins and Lewis Lloyd — were kicked out of the NBA after testing positive for cocaine. He said in a 1987 Spokane Chronicle article that that he knew they had problems, but "as a player, you can't tell another player anything. Those guys would look you straight in the eye and tell you they were clean." Ehlo, for his part, says he never used drugs in the NBA, only Advil.

Ehlo lists Aug. 1, 2013 as his clean day. He spent 30 days at Gosnold before he came back to plead guilty to a charge of second-degree reckless burning. He didn't have to spend more than that one day in jail, but that was enough for him, he says. He still goes to Narcotics Anonymous meetings around town and meets with a group from his church for more help. He's able to spend time with his family again, and he says they've supported him through his recovery.

He remembers, at Gosnold one day, hearing the story of an older man who asked his doctor if he could have a pill that would make the addiction go away. The doctor said there is no such pill. That, Ehlo says, helped him understand what it would take to get better.

"The amount of work that I put in to be a pro basketball player helped a lot, in the sense that I knew I was gonna have to do a lot of work to beat the addiction. And I can't do it by myself. I had tried that a bunch of times, but the meetings, the education, the support of my family, has all been tremendous," he says. "In the community, no one says, 'That's Craig: the addict.' I'm still kind of viewed as someone in the community that can offer something."

THAT WINNING FEELING

High school students and their families had nearly filled the Spokane Arena. Ehlo, at 6-foot-7, wore a suit and red tie, and towered over the Yakama Nation Tribal School's basketball coach, asking him questions before broadcasting the team's State B semifinal game for SWX.

As the high school bands blared music during timeouts, Ehlo and his broadcasting partner, Dave Cotton, talked basketball. When the game was over, Cotton posed for a picture with Ehlo.

"I just think the world of the guy," Cotton says. "Really, the community is fortunate to have him, and I pinch myself when I'm calling a game with him."

Ehlo loves being around basketball, whether it's youth games or the pros. Broadcasting happens to fit his schedule more than the demands of being a coach did, and he likes doing it because "I know what I'm saying." He recently sent the Pac-12 Network his résumé in hopes he could do more broadcasting soon.

When he used to call Gonzaga games, he remembers Chicago native Jeremy Pargo re-enacting The Shot with another player on the team. Things like that irritated Ehlo at first, but he eventually shook it off.

"I think I turned it into kind of being an honor," he says, "instead of a dishonor."

Now he starts each day on his knees in prayer. One of his counselors at Gosnold had a saying: "If your pills were on the floor, you'd be on your knees to find them."

Jani, he says, is typically already up before him, going 100 miles an hour. He walks the dogs, something that has become his best therapy and most physically demanding task.

If it snows, he'll shovel the sidewalk. If he has games to broadcast, he'll do some research. Otherwise he and Jani stay at home. Their three kids have all moved out, but they often go on family trips. Earlier this year, he and Austin went to Cleveland to catch a few Cavs games. Last week, they took a family trip to Arizona.

"I think Gavin said it best: 'I got my dad back,'" Ehlo says. "I can't say it any better."

In the NBA, Ehlo was always chasing the championship ring he never got. After everything he's been through, that hasn't changed.

He coached the Rogers High School basketball team in the early 2000s, hoping to get the Pirates at least to a district championship. When he got into broadcasting for the Sonics after that, he was hoping they'd win a championship, because the team's broadcasters also received rings. He went to EWU as a coach for a chance at a Big Sky Conference ring.

He's learned to embrace both the wins and the losses, but he'll always strive for that feeling of victory.

"At any level," he says, "that probably is the underlying thing that you chase." ♦