Dr. H. Gilbert Welch makes people uncomfortable. He seems intent on upending a key tenet of modern health care: early diagnosis and treatment is best.

The Dartmouth professor, physician and author of Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health visited Spokane in February for the 2014 Stier Lecture.

The capacity crowd of health professionals, students and community members listened attentively as Welch outlined his theory: Otherwise healthy Americans are being needlessly — even harmfully — given diagnoses and treatment for conditions that would have never caused them any real problems.

The conundrum of overdiagnosis is that it can only be identified when the condition is left untreated and nothing bad happens. That's not a risk many clinicians, or patients, are comfortable taking. "Once we have a diagnosis, we tend to treat everybody," said Welch.

So is it even wise to look for problems? Welch tackles two diseases with the biggest screening efforts: breast cancer and mammograms; and prostate cancer and PSAs.

"The PSA is a simple blood test but it raises some of the most complex issues in medicine. 'Do you want the test?' My personal right answer for me is 'No, I don't.' That's not the right answer for everyone."

Mammograms raise similar questions. Of a thousand 50-year-old women undergoing mammography for 10 years, statistically speaking, 0.3 to 3.2 will avoid a breast cancer death. More than half will have at least one false alarm, 70 to 100 of them will undergo a biopsy, and three to 14 will be overdiagnosed and treated needlessly with surgery, radiation, and or chemotherapy, Welch says.

"To me, if you take 1,000 well patients and in a 10-year course, you alarm half of them, that's outrageous," he says.

He suggested a course correction is underway, with other criteria perhaps being added to a diagnosis of cancer: "There are hints that bigger lesions are more important than small ones. Should we add a dynamic dimension to our diagnosis? Should we ask whether things are growing?"

Ultimately, Welch says the medical system has failed to distinguish between two types of prevention: early diagnosis and health promotion. "Health promotion is what your grandmother would have told you: Get plenty of sleep, eat your fruits and vegetables, go play outside, don't start smoking. It's not high-tech. It's positive. Be healthy."

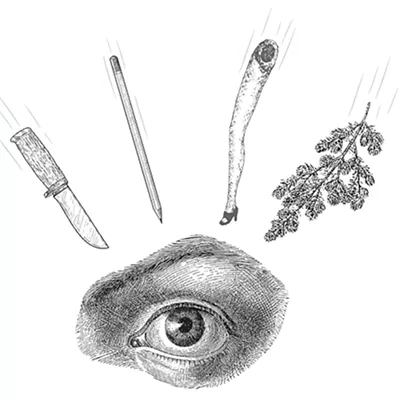

Conversely, early detection can create a sense of foreboding. He recalled a thyroid cancer awareness campaign with the tag line "Confidence Kills."

So, "If you feel good, you're about to die," Welch deadpanned, to laughter. But more seriously, he continued: "The basic idea of screening is look hard for things to be wrong. But health is not just the absence of any abnormality. It is also a state of mind, and we have to be very careful not to disturb that." ♦