You may have heard a story like this before.

A kid is smuggled into the United States when she's still a toddler. She grows up in America and later marries an American — a sergeant in the Army who goes to fight in Iraq. But then she makes a big mistake. She visits Mexico for Christmas and returns illegally. And that means she can't become a legally permanent resident unless she leaves the U.S., stays in Mexico for 10 years and then applies for legal status.

She walks into an immigration attorney's office, looking for help. That attorney's name is Raúl Labrador.

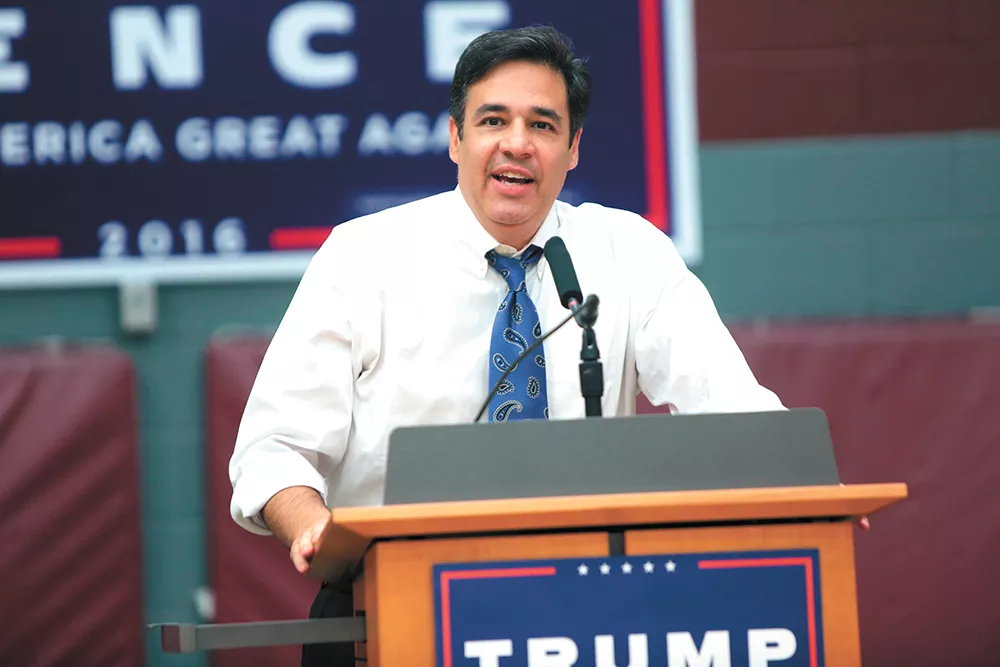

Labrador shared this story during a panel discussion at the City Club of Boise in 2007.

"That is ridiculous," Labrador said then. "I could not believe there was nothing we could do to help her."

At the panel, Labrador's answers were nuanced. He discussed employer crackdowns and internal security measures, but also urged reforms to help the people already here.

"I'm personally, I guess, more of a moderate on the immigration question," said Labrador, who joked that immigration was one of the few issues where "anyone will say I'm to the 'far left' of anything."

He said he had come to doubt that comprehensive immigration reform was feasible, and suggested that Congress should make smaller changes first. He pointed to two small changes that could be made to help his client, in particular. The first was to tweak part of the Immigration and Nationality Act that requires a citizen leave the country for 10 years to become legal.

"The second small change is a bill called the DREAM Act," Labrador told the audience.

He said it would give children of unauthorized immigrants who are high school graduates or college students an opportunity to become legal.

"They wouldn't have just helped this particular individual, they would have helped millions and millions and millions of people," Labrador said then about the two reforms. "The problem with the law right now is it doesn't make any sense. ... It puts too many barriers in front of people."

A lot has changed in the past decade — including Labrador's support of these so-called Dreamers.

After the DREAM Act died in Congress, President Barack Obama created a policy in 2012 known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, protecting nearly 800,000 children of unauthorized immigrants from deportation. But earlier this month, President Donald Trump ordered that DACA be phased out in six months.

Now, as both parties scramble for a compromise, few stand to wield as much power in the immigration debate as Labrador. While Trump now indicates that he might work with Democrats to protect Dreamers — taking many Republicans by surprise last week — Labrador, chairman of the House Immigration and Border Security Subcommittee, rejects that notion.

"No," Labrador tells in the Inlander in a phone interview. "I'll never trade any kind of amnesty for anything."

In 10 years, Labrador went from saying the DREAM Act would "help millions" to condemning it as "amnesty."

"If they're found to be here illegally, they're going to be deported," Labrador says when asked what he would say to immigrants losing their protections. He says that Trump now has major leverage to force serious immigration reform.

Labrador argues that his position has never changed. Instead, he points his finger at Obama's record and Democrats' priorities. It's the world that's different now, Labrador says, compared to the way it was 10 years ago.

HE'S NO MODERATE

Today, Labrador says he's no moderate on immigration. He says he's never been a moderate on immigration, and dismisses his self-description as a moderate in 2007 as a joke.

Labrador, born in Puerto Rico, spent 15 years as an immigration attorney. With less than a year and a half left in his fourth term in Congress, he's now running for Idaho governor in 2018. He still supports fixing the "ridiculous" aspects of the Immigration and Nationality Act and improving the visa system, but his recent record shows just how focused Labrador is on first cracking down on illegal immigration.

One bill he co-sponsored would hand states and cities the ability to enforce immigration policy. Another Labrador-introduced bill would allow states and municipalities to refuse to accept refugees.

But don't think that his overarching concern is handing local governments more control: In the past few months, he's also praised bills punishing local jurisdictions that refuse to help federal law enforcement with immigration enforcement.

"I have always said we need to do something for these children who are brought here through no fault of their own."

Labrador says there's very little difference between his immigration agenda and the one Trump campaigned on: Implement serious immigration enforcement measures before seeking to help unauthorized immigrants already here. In essence: Giant wall first; big, beautiful door later.

While he praised the DREAM Act in 2007, Labrador says the context was different back then. That was during the Bush administration.

"You had an administration that was trying to enforce a law," Labrador says. "Since then, we've had eight years of an administration that willfully failed to enforce the law."

President Obama's record on immigration is more complicated than either his critics or supporters generally admit. Some immigration advocates dubbed him the "deporter in chief," due to Obama's policy of officially removing illegal immigrants detained at the border, instead of allowing them to voluntarily return to their countries.

But as the recession diminished the draw of the American economy, border apprehensions fell significantly during Obama's tenure. And as he enacted policies to only deport criminals, overall removals fell as well.

"During his first term, he did deport a record number of people inside the United States, but during the second term he narrowed the scope of deportations significantly," says Randy Capps, a policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute. "It was a dramatic shift."

Labrador argues that Obama inappropriately focused on helping the 12 million unauthorized immigrants already here instead of fixing the flawed system, spurring more illegal immigration.

In particular, conservatives were infuriated by Obama's use of executive power to change immigration policy. In 2012, after the DREAM Act failed to pass, Obama took executive action. While his DACA policy didn't provide the path to citizenship like the DREAM Act would have, it protected hundreds of thousands of young immigrants from deportation.

Then, on Sept. 5, facing the prospect of defending DACA against lawsuits in court, Trump announced he was ending the program. Democrats were outraged. Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson joined more than a dozen states in filing a lawsuit against Trump's decision, arguing that it violated constitutional due process and equal-protection guarantees.

But Labrador heaped unvarnished praise upon Trump's decision, calling DACA unconstitutional and arguing that it undermined the rule of law.

"The reason Trump won the presidency is the American people don't trust Congress right now, and don't trust the American government to enforce the law," Labrador says.

Labrador believes that Trump has the credibility to be able to effectively win the trust of a reform-wary public in order to modernize the immigration system. And that, he says, should make both sides happy.

"I've said to immigration advocates that they shouldn't look at Trump as an enemy," Labrador says. "He's actually a friend."

Ultimately, Trump may be more of a friend to immigration advocates than Labrador anticipated. Last Wednesday, Democratic congressional leaders Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi announced they were striking a deal with Trump — protecting DACA recipients in exchange for increased border security. Iowa GOP Rep. Steve King worried that the deal would mean the Trump base would be "blown up, destroyed, irreparable, and disillusioned beyond repair."

But Labrador remained quiet. Last Thursday, he declined to comment on Trump's apparent reversal. After all, no deal had officially been made. So far.

BOTH SIDES

During his first congressional campaign seven years ago, Labrador saw exactly how little Idaho trusts the government on immigration. In 2010, both Democratic and Republican opponents accused Labrador of being too soft on immigration.

His primary opponent, Vaughn Ward, compared Labrador's work as an immigration attorney to lawyers who represent terrorists. Even the Democratic incumbent, Walt Minnick, launched an ad arguing that illegal immigration was "good business" for Labrador as an attorney.

"He almost wants people to believe that I'm an illegal immigrant," Labrador scoffed at Minnick's ads during a 2010 debate.

Labrador called for enforcing current laws and stationing the National Guard at the border. A month after the Department of Justice sued Maricopa County, Arizona, Sheriff Joe Arpaio for stonewalling an investigation into racial discrimination, he touted Arpaio's endorsement.

When Idaho Statesman journalist Dan Popkey raised Labrador's previous support for the DREAM Act during a 2010 debate — asking why he was "pandering" on immigration — Labrador argued that the details of policy were the issue, not the concept. (Today, Popkey works for Labrador, as his press secretary.)

"The general concept of the DREAM Act, I'm in favor of," Labrador responded. "I have always said we need to do something for these children who are brought here through no fault of their own."

But he said he objected to pieces of the act allowing unauthorized immigrants to receive in-state tuition, and not requiring them to leave the United States before returning to become U.S. citizens.

In a 2010 press conference concerning immigration, Labrador planted his flag on the middle ground: He called for enforcement of existing laws and improving border security. He stressed a proposal he'd floated at the Boise City Club forum, requiring immigrants to leave the United States before getting in line to become legal. But he also called for compassion, reminding the audience that unauthorized immigrants "too are children of God."

"I would offer illegals who have a desire to become legal, productive members of our society an incentive to come forward," Labrador said. "Should they do so willingly and within some reasonable time frame, we would give them consideration by the State Department to return legally."

Today, Minnick's former campaign manager, John Foster, argues that while Labrador has a complex position on immigration, he hasn't wavered from that.

"Whatever your view of him politically, he is intellectually consistent," Foster says. "I think that the perception that he is more hard-line doesn't take into account all the other things that have happened since 2010."

But Brian Tanner, a Twin Falls immigration attorney who worked with Labrador occasionally when the congressman was still practicing law, sees a dramatic change.

"At the beginning, he made that choice: 'I wanted to help immigrants.' This isn't something you step into because you want to make gallons of money," Tanner says. "He's way more hard-line now than he was. No question... He's now lockstep with Trump."

The only question in Tanner's mind is why Labrador changed.

"I'm not sure if it's a political thing or it's sincere," Tanner says. "Attacking immigrants is politically popular. It has been from the beginning of time."

WOULD-BE REFORMER

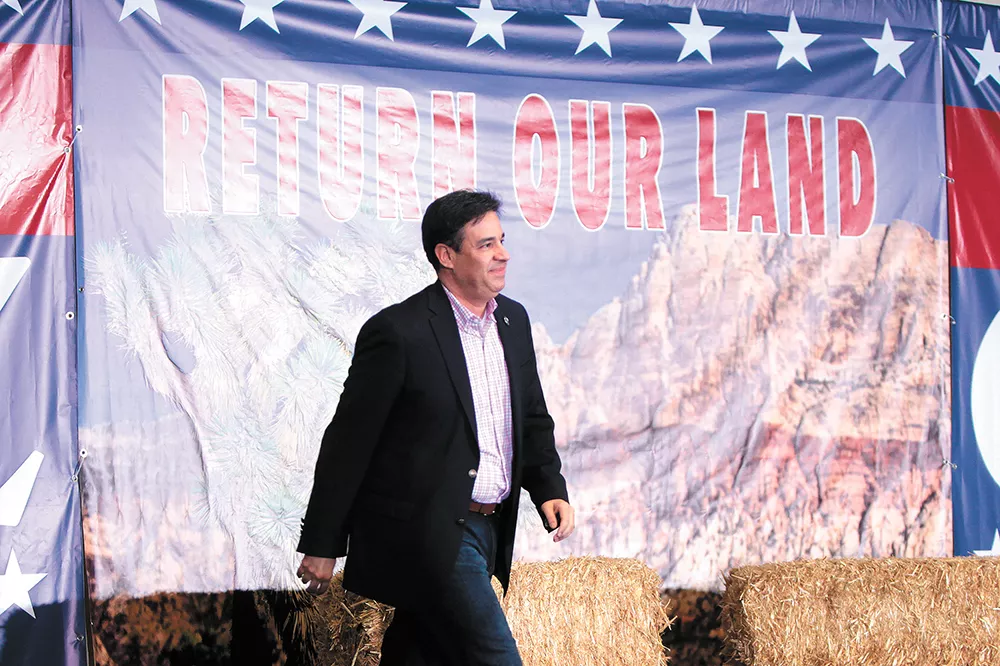

After the Tea Party wave propelled Labrador to a sizable victory in 2010, he quickly became a celebrated figure within the conservative movement. Even before he became a major player in the right-wing Freedom Caucus, Labrador was beloved by the right for telling Republican establishment leaders they failed because they were too eager to roll over for Democrats in exchange for scraps.

Labrador was not the symbol of compromise — he was the symbol of defiance.

Yet immigration reform advocates saw Labrador as one of their best hopes to convince the Tea Party faction regarding comprehensive immigration reform.

"He sees the human side of immigration, the families that are being ripped apart by deportations," fiercely pro-immigrant Democratic Rep. Luis Gutiérrez of Illinois said in a 2013 statement to the Inlander. One of Labrador's closest friends in D.C., Gutiérrez met with Labrador regularly to discuss immigration.

That year, Labrador was a member of the "House Gang of Eight," a bipartisan group of representatives looking to hash out a comprehensive immigration bill.

A Washington Post article around that time called Labrador the "middleman" on immigration, quoting him criticizing the Republican Party's hard-line views on the issue.

"They're moderate on every other issue, and they think this is the one issue where they have to become conservatives," Labrador told the Post. "I feel the reverse."

The article highlighted his belief that unauthorized immigrants could obtain legal status through a "nonimmigrant visa," but also noted that his moderation earned him flak from Idaho constituents.

But in June 2013, Labrador left the House Gang of Eight, effectively signaling the death knell for immigration reform: In particular, he had refused to support any bill that helped unauthorized immigrants pay for health care.

Yet this scenario had been posed at the 2007 panel: How can American taxpayers afford to support the "social and medical needs" of unauthorized immigrants?

Back then, Labrador acknowledged that immigration reform would result in formerly illegal immigrants receiving more social services, but said that the social welfare debate should be considered separately from immigration.

"We cannot afford as a society to pay for all these social programs, but I don't want to distinguish between aliens and non-aliens," Labrador said.

Today, asked about what seems to have changed, Labrador suggests that it's obvious.

"I'm not sure if you're obtuse, or if you're doing it on purpose. What you're missing is that ... in 2007 there wasn't an Obamacare," Labrador says. "In 2007, there wasn't any concern about illegal people getting free health care."

In the years since, Republicans and Democrats have drifted further and further apart on immigration.

"If I've changed on anything, I assumed that Democrats in good faith would come to the table and deal with their border security issue," Labrador says.

He doesn't believe that anymore.

THE LABRADOR LEGACY

Today, when Labrador speaks about his 15 years as an immigration attorney, he doesn't dwell on anecdotes of hardworking Americans facing deportation. Instead, he cites a different lesson: "I saw an immigration system that, instead of preventing illegal immigration, was encouraging illegal immigration."

In 2010, Labrador closed his immigration press conference by reading from Ronald Reagan's January 1989 farewell address about America being a shining city upon a hill, where "the walls had doors and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here."

Today, Labrador says that Reagan's 1986 amnesty of 3 million illegal immigrants is a clear lesson in how disastrous it would be to allow legalization to take place before more enforcement.

After the 2012 presidential election, Labrador slammed Republican nominee Mitt Romney for his inartful comments about immigration that hurt him with Hispanics, but today, Labrador praises Trump's approach.

"Some of his rhetoric was strong because people were missing the point about what's important with immigration reform," Labrador tells the Inlander. "I think you do, and I think many people do."

When he hears politicians or reporters express concern about DACA recipients, he says that's the wrong focus.

"Many Republicans make this mistake where they start talking about DACA — you know, the first thing that comes out of their mouth is 'DACA'," Labrador says. "The concern that American people have is mostly, 'Do they feel safe and secure in the United States?'"

Most research suggests that immigrants, legal and illegal, actually commit crimes at lower rates than do native-born citizens. But Labrador has targeted exceptions: Last week, the House passed a Labrador bill allowing deportation of members of criminal gangs, like MS-13, even before they commit deportable offenses.

He's still developing legislation reforming other pieces of the immigration system — expanding the number of visas for farm workers, for example — but there's not much more time left on the clock.

If Labrador is elected governor in 2018, it would mean giving up the unique power he wields on the immigration debate. And there's no guarantee that the person who replaces him will hold the same values. One candidate, Idaho State Rep. Luke Malek, who represents Coeur d'Alene, argues that Obama's executive order overstepped its bounds and that Congress needs to protect the DACA recipients.

"Congress needs to step up and ... take care of this issue," Malek says. "These are model citizens that we want in this country."

Labrador says he took the immigration reform issue into consideration before running for governor.

"The reality is, if it doesn't happen this term, it's not going to happen," Labrador says. "Next term is a presidential election term. Big things like this don't happen in a presidential election term." ♦

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: DANIEL WALTERS covers Spokane City Hall, business and development for the Inlander. Since 2008, Walters has followed house-flippers sniffing out foreclosures during the recession, dug into the mess that dogged the vacant Ridpath Hotel for nearly a decade, and explored the dramatic economic disparity between the swanky Kendall Yards and the low-income West Central neighborhood that borders it. He currently rents a one-bedroom apartment in Browne's Addition. Reach him at danielw@inlander.com or 509-325-0634 ext. 263.