The year of 1858 was a busy time in the lands we now call the Inland Northwest. White settlers were negotiating treaties that transferred vast areas to them — treaties that were later opposed by many of the tribes affected by them. A Continental Divide railroad crossing was being sought in the northern Rockies. And the U.S. Army was building a military road connecting Fort Benton to the Pacific Ocean. It's no surprise that the experiment exploded in violence that year, with skirmishes at Steptoe Butte, Four Lakes and Spokane Plains.

It was a year that changed the region forever. You can read about it in history books, but because a quiet private with a pad of paper and a pencil was on hand, there's a visual record, too. In a decade spent trudging across the Pacific Northwest, Gustavus Sohon recorded that brief moment when the region was settled.

A German From Brooklyn

During the decade that began in 1853, the nascent territorial government began to formalize its control over the Columbia Plateau, with the governor himself, Isaac Stevens, heading up the landmark railroad survey that would link Washington to the rest of the United States. Stevens soon embarked on his grand tour of treaty councils with the whole sweep of Plateau tribes, which would lead to confusion, clashes with miners and settlers, the bitterly divisive wars of 1858 and, ultimately, the dispersal and removal of tribal people to the current reservations. As the decade drew to a close and the United States dissolved into the chaos of the Civil War, Captain John Mullan scratched out his wagon road across the mountains to Fort Benton, etching the line for modern Interstate 90.

Sohon bore witness to every one of these events. Serving first as an Army private and then as a contract surveyor and translator for the U.S. Army, over the 10-year span Sohon amassed a catalog of work that includes more than 200 manuscript drawings, maps and field notebooks. As a character in history, he remains an elusive figure, almost invisible in the larger vortex of events that swirled around him. But his artwork illuminates this crucial decade with a clarity and balance that no one else on the scene was able to achieve.

Gustavus Sohon was born in Tilsit, Germany, in 1825. Family lore had it that he emigrated to America to avoid conscription into the Prussian Army when he was only 17. By that time the teenager already spoke English, French and German fluently. His daughter later spoke of her father having attended "University," though nothing more is known of Sohon's education or background. The boy settled in Brooklyn, where for 10 years he lived quietly, finding employment in an odd assortment of skilled trades that included bookbinding, woodcarving and photography. Then, in July 1852, for unknown reasons, Sohon enlisted in the U.S. Army. The military paperwork on his enlistment described him as five feet and seven inches tall, with a dark complexion, hazel eyes and black hair. The new private was assigned to Company K, Fourth Infantry Regiment, and within a few days he shipped out for the Pacific Coast. After a brief stop in San Francisco Bay, the new private sailed up the Columbia River to the frontier military post at The Dalles and settled in for the fall.

Sohon was still at Fort Dalles the following spring when Gov. Isaac I. Stevens, the first governor of the new Washington Territory, was ordered to explore between the 47th and 49th parallels for a northern railroad route connecting the Mississippi River to Puget Sound. Stevens left St. Paul, Minn. in June 1853, while his assistant, Captain and future Civil War general George B. McClellan, surveyed east from the Pacific. At the same time, Lt. Rufus Saxton moved east from Fort Dalles with an escort of 18 soldiers that included Gustavus Sohon. Their assignment was to establish a supply depot at the Flathead Indian village of St. Mary's in Montana's Bitterroot Valley.

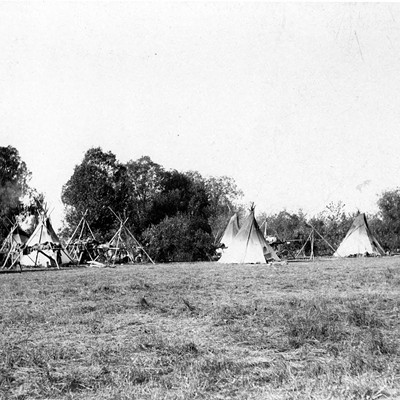

Saxon's party followed the traditional Road to the Buffalo, from the Spokane River to the Sinyakwatin crossing of the Pend Oreille River, over the top of Lake Pend Oreille, and up the Clark Fork into what is now Montana. Along the way they met a party of a hundred Salish Indians returning from a buffalo hunt, laden with robes and dried meat for trade. They also met the owners of the Fort Owen trading post, who were leaving St. Mary's because of constant threats from the Blackfeet. The store owners turned around at the sight of the soldiers, and soon opened for business again in the Bitterroot Valley.

Meeting Native People

By the fall of 1853, Governor Stevens understood that his most important decision as far as the railroad was concerned would be the route of the pass over the Rocky and Bitterroot mountains. Accordingly, he left Lt. John Mullan with party of 15 soldiers to winter in the Bitterroot Valley, take precise weather observations, and survey the country for likely routes. Private Sohon was included in the group, which built a few log cabins near modern Stevensville and settled to their task.

It was over this winter of 1853-54 that Sohon began to distinguish himself, first by absorbing the Salish language with astonishing speed and serving Mullan as an interpreter. The private gathered information from the tribes about the landscape along the Continental and Bitterroot Divides, including their many trails and mountain passes. He also began to compile a dictionary of 1,500 Salish words and phrases. Sohon was with Mullan during mountain forays that ranged from the Snake to the Kootenai River. They crossed the Continental Divide no less than six times, measuring snow depths and taking temperature readings. Along the way, besides working as a weatherman and cartographer, Sohon sketched a series of landscapes that provide an invaluable record of not only Mullan's journey, but of the countryside itself.

During the spring and summer of 1854, while traveling between the Kootenai River, Flathead Lake and the Bitterroot Valley, Sohon drew ink portraits and wrote some brief notes describing several local native people that he became acquainted with, including Flathead, Pend Oreille and Iroquois who had emigrated into the region with the fur trade. Because they depict the rich variety of Plateau tribal culture, these portraits have come to be viewed as part of the essential history of our region.

Most of the private's subjects had been baptized by the Jesuit missionaries, and Sohon must have come to know some of the brothers well. Many of these missionaries were also accomplished linguists, and their influence on Sohon is evident in the biographical sketches the private wrote, which tend to emphasize the virtuous character of his subjects. But Sohon also included important ethnographic details as well, noting each person's tribal name, his own translation of it into English and the baptismal names bestowed by the Jesuits. The private included color codes so that every article of dress and decoration could be visually available. He sorted out the tribes to the best of his ability and specifically dated each sketch.

Sohon's keen, perceptive style is evident in the only female subject in this group of sketches, a Kalispel woman whose name he rendered as Pagh-Paght-sem-i-am, "The woman of good sense." A neat headband that sets off the Kalispel woman's flowing hair provides the only ornament, and the artist captures her with a few quick lines, focusing on the deep concentric circles around her eyes. She stares off the page with a searing intelligence that is impossible to ignore.

Spokane Garry presents quite a different front. Garry, who did not give a tribal name to Sohon, was taken to Red River as a child in 1825 to be educated in the British manner. After his return in 1829, he moved among missionaries, fur men, white settlers and the tribes. Although the settlers tended to exaggerate Garry's political importance among his own people, there is no question that over time he became a forceful spokesman for the interests of the native tribes. For Sohon's portrait, Garry was garbed in a European collared shirt, with a ruffle touching his chin. A thick sash draped over one shoulder, set off by a fashionable fur trade cap. He seemed almost to smile out at the man who was capturing him for the ages, and Sohon titled the portrait "Head Chief of the Spokan Tribe." But the real marker of this picture is that Spokane Garry could write as well as any white man, and signed his own signature to the portrait. Sohon testified to the fact by adding "The above Name is written by Garry himself."

A Translator at Treaties

By the fall of 1854, Lt. Mullan's detachment was back at Fort Dalles. Mullan's review of Sohon's performance was so glowing that in the spring of 1855, Sohon was assigned to accompany Gov. Stevens' expedition that would sign the first treaties between the U.S. government and a host of Columbia Plateau and Plains culture tribes. Stevens' report shows that he understood the abilities of his new recruit:

"I also secured the services of a very intelligent, faithful, and appreciative man, Gustavus Sohon, a private of the Fourth Infantry, who was with Mr. Mullan the year previous in the Bitter Root valley, and had shown great taste as an artist, and ability to learn the Indian language, as well as facility in intercourse with the Indians."

In late May and early June, Gov. Stevens and Gen. Palmer of the U.S. Army met with members of the Walla Walla, Cayuse, Umatilla, Yakima and Nez Perce tribes at the Walla Walla Council, only a few miles from the abandoned Indian Mission of Marcus Whitman. The tribes signed three separate treaties on June 9, which ceded almost 60,000 square miles of land over to the United States. The scope of the treaty and the diversity of the people they attempted to control were more than any piece of paper could encompass — Stevens' designation of "Yakima" included 13 groups that spoke three mutually unintelligible languages — and it came as no surprise that the agreement immediately became a subject of intense controversy.

During the proceedings, Private Sohon provided interpretation for a group of Spokane Indians who attended the talks. He wrote up a parallel English-Salish text of Gen. Palmer's opening speech. He executed pencil sketches of the opening parade of the Nez Perce, and several portraits that included both U.S. and tribal negotiators. Sohon attached brief biographies to several of the tribal portraits that expounded on the upright character and integrity of the leaders at the treaty. Although these paragraphs tend to run together in their complimentary detail, they provide a record of distinct individuals at a time when most whites — including, by the sound of his paternalistic speeches, Gov. Stevens — saw the American Indians as a race beneath them.

From Walla Walla, the Stevens party moved east to a gathering at the Hell Gate, near modern Missoula, to meet with leaders of the Flathead, Upper Pend Oreille and Kootenai tribes. Another complex treaty was signed on July 16, involving 25,000 square miles of territory. Gustavus Sohon and a Shawnee named Ben Kiser served as the official interpreters at this Flathead Treaty Council, and Sohon's sketch of the meeting in session is the only pictorial record of the parlay.

Stevens continued his tour, crossing the Divide and meeting with Pikani, Blood, Blackfeet, Gros Ventres, Nez Perce, Flathead and Upper Pend Oreille leaders on Oct. 16 at the mouth of the Judith River. Again, Sohon and Ben Kiser translated for the Salish-speaking tribes, and Sohon made a series of impressive sketches. A treaty, negotiated in a single day, defined hunting ground boundaries to separate tribes from west and east of the mountains, but this time the tribes ceded no land to the U.S. government. Isaac Stevens and his party turned around to head east, hoping to make it back over the Divide before the weather turned.

Violence Erupts

Stevens planned one more bargaining session during his return journey, which was to include the Spokane, Colvile and Coeur d'Alene tribes. But as soon as he started west, a messenger brought news of trouble between whites and members of the tribes who had signed the Walla Walla treaty. Twelve days after the last Walla Walla Treaty had been signed, the Oregon Weekly Times had published an announcement that seemed to invite settlers and miners into the country east of the Cascades. This was a clear violation of the tribal understanding of the new agreement, and such encroachment, combined with increasing numbers of California gold miners who were filtering into tribal territory looking for new digs, provided a recipe for certain violence.

Stevens stopped at Fort Benton on the upper Missouri to obtain more firepower, and pressed on across the Coeur d'Alene range through heavy snow. He imperiously called for a council and met representatives from the three tribes just east of modern Spokane in early December 1855. But Sohon did not serve as the interpreter this time, because Spokan Garry was there, fluent in English and outraged at the fact that white settlers were moving onto tribal lands before the treaties went into legal effect. Garry made a forceful argument that countered Gov. Stevens' customary paternalistic treatment of the tribe. Perhaps reflecting the tense situation among the participants, at this council Private Sohon made no drawings or portraits at all. In the end, no papers were signed.

Stevens' party was back at Fort Dalles by the end of the year. Private Sohon spent the remainder of the winter in the service of Gov. Stevens, then was assigned to Fort Steilacooms, Washington Territory. In the fall of 1856 he was transferred to the headquarters of the Topographical Engineers in San Francisco Bay, where he served as a draftsman and prepared maps. He must have continued to travel, however, because at the end of his five-year enlistment, in July 1857, he was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army at Fort Walla Walla, Washington. But that wasn't the end of his work with the military.

Isaac Stevens's plan for a practical route across the northern Rockies had never quite been accomplished, and in 1858 Stevens, still the governor of Washington Territory, engineered a Congressional infusion of money to conduct a survey and begin the work. He named Lt. John Mullan as the officer in charge, and one of Mullan's first acts was to hire Gustavus Sohon as his guide and interpreter. In May 1858, Sohon was once again part of a small military party that struck out from Fort Dalles. Once again, the first day on the road ended with a messenger bringing news of Indian wars: Col. Steptoe's brigade had been roughed up by Plateau people near modern Rosalia, directly on Mullan's intended route. Although there is no evidence that Sohon was present at the Steptoe battle, the Library of Congress does hold a pencil sketch on tri-colored paper entitled "Battle of Col. Steptoe on the In-gos-so-man Creek, W.T., Fought 17th May 1858." The sketch depicts troops and Indians skirmishing, and it agrees with a map of the battle compiled by John Mullan, Theodore Kolecki and possibly Sohon. The most likely scenario for this sketch seems to be that Sohon reconstructed the battle scene while examining the grounds with Captain Mullan some months after the fact.

After receiving the news of Col. Steptoe's defeat, Mullan returned to Fort Dalles, dispersed his party, and offered his and Sohon's services to the pleasure of commanding General Clark, who designated Mullan as topographical officer for Colonel Wright's force of 680 soldiers. That is how Gustavus Sohon came to be present at the historic battles of Four Lakes on Sept. 1 and Spokane Plains on Sept. 5, 1858. Sohon used the opportunity to make a sketch on the Spokane Plains (near the Idaho state line) that captures the tipping point of the second battle. His drawing shows the action after a combined force of Coeur d'Alene, Spokane and Palus set fire to the bunchgrass as they retreated from Wright's force. In the confusion of smoke, the tribal combatants closed in on Wright's troops on three sides. Wright circled his pack train and set up a line of riflemen, armed with modern weapons that completely outgunned the tribe's trade muskets, bows and arrows, and lances.

The outcome of the fight was a foregone conclusion, and Wright's orders afterward, designed to break the spirit of the enemy, were to systematically shoot a large number of captured horses. Sohon responded with an accurate sketch of the incident, entitled "Horse Slaughter Camp, Sept 9th, 1858; 800-900 horses killed." In his view the killing ground, sullied with an incoherent smear of blood, engulfs the center foreground of the small sketch. To the left rises a straight line of rifleman, working in the style of military executioners. A scatter of living livestock, including some long-horned bullocks, fans from the center background across to the right, dwindling as it circles around to a single living horse. This animal stands over a fallen pony. Sohon's sketch remains a haunting image of an incident that fostered generations of ill will between tribal people and American settlers.

In between the actual battle and the day of the horse slaughter, Sohon made an ink sketch of the army encampment of Sept. 6. The site looks like it was on a stretch of the Spokane River above Big Eddy. In this pencil drawing of minutely fine detail, the slopes on both sides of the river are cloaked in an unbroken forest of well-spaced coniferous forest. Big ponderosa pines on top give way to open shrub-steppe along the benches. A line of mules breaks down off the plateau, making their way to the river for water. The Centennial Trail between L.T. Meenach Bridge and the George Wright Cemetery passes through much the same habitat today.

Apparently during the days around the battle, Sohon also sketched a view of the lower part of Spokane Falls. Once again the artist showed a real feel for the open pine and basalt landscape of the river. In the altered cityscape of today, it is difficult to tell exactly where Sohon was standing, and he seems to have glossed over the intricate lacework of islands above the lower falls. When matched against historic records, the river appears to be running at a high level for September; either thunderstorms that had hindered the troops' maneuvers over the previous week had raised the river level or the artist exaggerated the billowing foam of the falls.

The 11 illustrations Sohon completed during the Wright campaign provide the only visual clues we have to match up to first-person oral and written accounts of the conflict. Sohon's work, although he may have used artistic license in some of his drawings and warped time in others, holds up very well when set against the most detailed of these other accounts. His previous experience in the region and with the tribes, combined with his knowledge of topography and military methods, made him an invaluable witness to the events that week around Spokane.

Siting the Mullan Road

Sohon and Mullan marched with Wright to three peace councils held later that month, but there is no record of whether Sohon served as a translator. Over the winter, Mullan traveled to Washington, D.C., to secure more funding for his road project, and in May 1859, the two were marching out of Fort Dalles for the third time. In June, Mullan, fully aware of Sohon's ability to communicate with the Salish tribes, dispatched his guide to explore a potential Bitterroot crossing south of the Coeur d'Alene River. But the Coeur d'Alene people had no intention of opening up a path for white soldiers and settlers that cut through the heart of their country. Sohon could not persuade anyone to guide him through the mountains.

After a month alone with the Coeur d'Alenes, Sohon returned to Mullan's camp and took charge of an advance party that followed another tribal trail across the Bitterroot Divide, marking out the route basically followed by Interstate 90 today. He crossed the Divide on a Coeur d'Alene trail about a mile and a half south of the present highway marker on Lookout Pass; Coeur d'Alene tribal members Felix Aripa and Noel Campbell still remember it today as marked by an artesian spring that brimmed with water all year long. During summer crossings and huckleberry season, the spring always put out water so cold that it would make their teeth hurt.

Mullan's survey team wintered in the St. Regis area, then continued their work the following spring. In July 1860, Sohon crossed to the upper Missouri to meet a detachment of 300 Army recruits under Major Black. He led them back from Fort Benton to Fort Walla Walla, a journey that marked the first wagon party to travel the route, and it was the success of Sohon's venture that convinced Mullan that the trail could be converted to a practical road. Over the next two years, Sohon continued to work for Captain Mullan as the road was systematically improved. After the field season of 1862, he traveled with Mullan to Washington, D.C., to assist in the preparation of maps and sketches for the official report on the road project. In the final product, 10 colored lithographs produced by the artist were mistakenly attributed to "C. Sohon."

Making a Home

At that point, Gustavus Sohon, never a man for the spotlight, disappeared entirely from the Northwest scene. In 1863, he married Julian Groh and moved to San Francisco, where he established a photographic gallery on Market Street. His most famous sitter was Father Pierre De Smet, who for years moved in the same Inland Northwest territory traveled by the painter, and knew many of the same Salish and Kootenai individuals Sohon had painted while serving as an Army private. Around the time of his marriage, Sohon also sat for a portrait of himself: peering out of an oval frame, he appears as a well-dressed, carefully groomed man with a solid gaze and the same intelligent eyes noted by the Isaac Stevens 10 years earlier.

After only two years in the Bay Area, Sohon gave up his business and moved to Washington, D.C., where he opened a shoe business that he operated for the rest of his life. He focused his considerable attention on his and Julia's eight children, many of whom went on to successful professional careers in a variety of fields. But even from across the continent, Sohon's personal correspondence makes it clear that he maintained a steady interest in the tribes of the Columbia Plateau. His old Nez Perce friend Lawyer, "Bat That Flies in the Daytime," may have stopped by the Sohon's home in the District of Columbia in 1868. When a Flathead Indian delegation under Chief Charlot came the nation's capital in 1884, they certainly visited Sohon. One of the artist's daughters later recalled that the only time she ever saw her father smoke was when a pipe was passed around to initiate the meeting of old acquaintances. But such a timely surprise was typical of Sohon, who seemed to blend into the very atmosphere of wherever he happened to be, completely unnoticed until he stepped forward to record it for posterity with a series of quick and confident strokes.

Jack Nisbet is a Spokane author whose latest book is Visible Bones (Sasquatch Books).

Publication date: 06/03/04