Last fall, the Pacific Northwest got the news that our region was chosen as one of seven regional "hydrogen hubs" around the country, with the promise of about $1 billion in federal funding to create, store and increase uses of hydrogen fuel.

The Pacific Northwest Hydrogen Hub, expected to create 10,000 or more jobs, will specifically focus on "green" hydrogen — using only renewable energy resources to power the electrolysis process that rips hydrogen atoms from the oxygen atoms in water to create hydrogen fuel.

When used in fuel cells, the only resulting emissions from burning that fuel are water and heat.

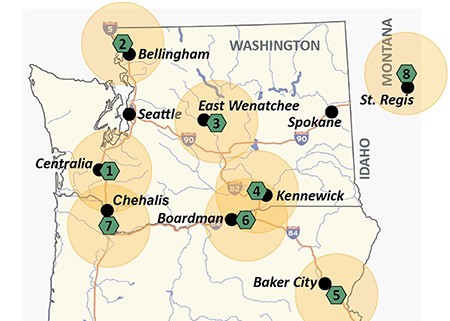

The regional hub includes proposed projects from 16 companies in Washington, Oregon and Montana. The team behind the hub is currently negotiating each of those projects with the Department of Energy, and could start the official planning process this spring.

The $7 billion put into the hubs over the next decade (from the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act) is expected to be leveraged for private and local matching dollars totaling nearly $50 billion, according to the Department of Energy. The hubs will play a key role in increasing hydrogen production, with the lofty goal of getting the price down to $1 per kilogram by 2031.

The primary goal is reducing greenhouse gas emissions, particularly from hard-to-decarbonize sectors like industrial manufacturing processes that require massive amounts of heat. Hydrogen can also fuel a variety of transportation methods.

Some environmental groups are wary, noting that some of the hubs intend to use natural gas (methane) to create hydrogen — a process that still emits carbon dioxide — and that burning hydrogen in industrial processes can create nitrous oxide, the third-most common greenhouse gas.

Despite the fact it's the most abundant element in the universe, isolating hydrogen with electricity is also really inefficient.

It takes about 50 kilowatt hours of electricity (about what the average household uses over two days) and 14 to 20 gallons of water to create 1 kilogram of hydrogen gas, which then only provides about 80% of that energy when burned, according to a Washington state Department of Commerce report released in January. By comparison, it takes less than a tenth of that energy to make 1 gallon of gasoline, which provides about the same output.

That's why it's key to produce hydrogen with renewable energy and to focus on energy-intensive end uses, says Robin Everett, the deputy western regional field director for the Sierra Club, who also serves on the board of the Pacific Northwest hub.

"A truly green hydrogen hub, made from renewable energy, is the only kind that Sierra Club endorses," Everett says. "If you are going to use more energy to make hydrogen than it provides, there better be a really good reason."

If something can simply be plugged in, such as electric vehicles or hot water heaters, Everett says we shouldn't look to transition that to hydrogen.

But for energy intensive industries, and fuel for aviation, shipping and long-haul trucking, hydrogen could be promising and help reduce climate impacts, Everett says.

"The thing that gets me out of bed in the morning on this issue is high heat manufacturing," Everett says. "I want to bring manufacturing back to this country and ... hydrogen is a promising way to power our industrial uses in a green way."

Aaron Feaver, the executive director of the Washington State University-led organization JCDREAM (the Joint Center for Development and Research in Earth Abundant Materials), which helped the region apply to become a hydrogen hub, agrees that hydrogen makes more sense in some uses than others.

For example, since fertilizer producers currently pull hydrogen from methane to combine it with nitrogen for their products, if clean hydrogen is available, the emissions can be reduced, he says.

"That'll be a really interesting and compelling project for farmers in the state of Washington," Feaver says.

Likewise, while hydrogen is less efficient for lighter vehicles than current battery-based systems, it may be more efficient for heavy-duty trucking that requires longer distances and crossing mountain passes, he says.

The Department of Energy plans to roll out funding for the hubs in four phases over the next decade, with hydrogen production slated to come online several years from now.

But because some smaller Pacific Northwest projects are already well past the planning phase, Feaver says he thinks some could start producing hydrogen far sooner.

"Some of the folks that have been aligned with the hydrogen hub are already out there doing projects in the region, and in some cases might be producing hydrogen through electrolysis later this year," he says. "We're going to need every tool we have in the toolkit in order to reach zero carbon emissions by the 2050 timeframe."♦