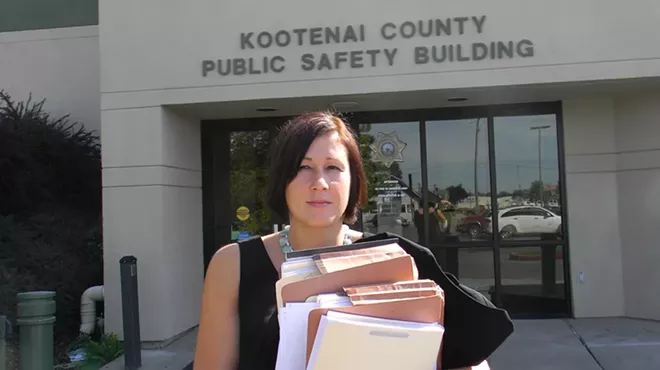

The bulky stack of papers look as if they'd slide from Lisa Chesebro's arms should she loosen her hold — even just a little.

This embarrassing nightmare scenario has happened before, with the brown accordion folders full of pleadings, complaints, paper clips, letters to the court and other critical documents tumbling out of her grasp and spilling all over the Kootenai County Jail parking lot.

Chesebro is one of Idaho's overloaded public defenders, someone paid with public funds to defend people who society at large would casually condemn to incarceration and second-class citizenship. It's Chesebro's constitutionally mandated job to make sure that drug users, thieves, the wrongly accused and otherwise benign people who make boneheaded decisions get their day in court. It's also a job that state officials acknowledge has been chronically neglected, and they're not sure what to do about it.

Chesebro opens the door to the county jail while clutching her mass of papers, stepping into the lobby where she waits to meet her clients. One is five months pregnant. Another has been diagnosed with mental illness, and another is facing what those in the field call "the bitch," a habitual offender designation that could mean a life sentence.

While Chesebro waits, she chats with Pastor Tim Remington — the director of Good Samaritan Rehabilitation who is here to offer inmates a Christian solution to drug and alcohol addiction — about their seemingly endless workload.

"We just take what's been given to us in life," says Remington. "Some things just come in like a flood."

After 15 minutes in the lobby, a voice heavy with authority and indifference booms through the intercom: "Attorney, go to Booth 5."

A metal door slides open and Chesebro enters a room with brick walls painted white, a gray carpet smudged with stains and six booths separated by glass panels scuffed from inmates striking the phone against them. It's here that she meets her first client, Stephanie Lewis, who emerges from behind a door on the other side.

Her pregnancy is starting to show from underneath her orange jail uniform. Her blue eyes carry a worried expression that brightens when she sees Chesebro.

Using the phones on either side of the glass panel, they discuss the charges against her: using a credit card she found on the street, burglary and possession of Oxycontin, and how it could help her get probation if her friends and family can be at her sentencing hearing this afternoon.

"I think it says a lot if they can be there," says Chesebro. "It shows you have a lot of support."

Chesebro herself can't make the hearing, and the news disappoints Lewis. If she were a private lawyer, it'd be different. Instead, Lewis' case will be passed to another public defender, a situation that's far from ideal.

"I should be there at every single court appearance, especially at sentencing," says Chesebro. "I don't have that luxury because I have to be at someone else's sentencing."

At any given time, Chesebro is juggling about 100 felony cases. The American Bar Association recommends that defense attorneys only take 150 felony cases per year. By comparison, the situation in Kootenai County isn't as dire as in other parts of the state, where poor defendants are churned through the system with minimal defenses.

State officials are increasingly recognizing the untenability of the predicament that attorneys like Chesebro face. There's a growing consensus in Idaho that attorneys like Chesebro are so overburdened that the Gem State's promise to the rights of the accused is routinely broken. Poor defendants often make their initial court appearances without a lawyer present, and many public defenders lack investigators and other resources that private defense attorneys would have access to.

"The courts have made it clear that our current method of providing legal counsel for indigent criminal defendants does not pass constitutional muster," said Gov. Butch Otter, in his State of the State and Budget address in January. Last year, former Idaho Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Burdick told lawmakers that "Idaho's public defender system today has significant deficiencies."

Now, after half a decade of studies and incremental reform, the Idaho chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union says the state still hasn't fixed what it considers to be the underlying problems of the system and is now suing, a strategy that has worked in other states.

Despite the lawsuit and near-universal agreement that the system is broken, few see a clear path to fixing it.

It's been more than half a century since Clarence Earl Gideon was charged with breaking into a Florida pool hall, sparking the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that would guarantee a lawyer to anyone charged with a crime. Gideon asked the court to provide him with an attorney. His request was denied, and he was sentenced to five years in prison while appealing his case all the way to the nation's top court. In 1963, the court ruled that the promise of the U.S. Constitution's Sixth Amendment to a fair trial included a lawyer at public expense for those who couldn't afford one.

At the time, 22 state attorneys general filed a brief arguing that the accused deserved a lawyer. Among them was Idaho, whose state court had ruled 40 years earlier, in 1923, that the indigent have a right to a lawyer under the state constitution.

"The unfortunate reality is that Idaho used to be a champion, historically," says Leo Morales, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Idaho, which filed a lawsuit in June against officials in charge of its public defense system. "Even before the state was granted statehood, already they were leaders in this."

In 2010, the National Legal Aid & Defender Association, at the request of the Idaho Criminal Justice Commission and Idaho Juvenile Justice Commission, delivered a damning 135-page report examining the state's public defender system. It concluded that the system is underfunded, public defenders are overburdened and defendants aren't getting the defense they're entitled to under both the U.S. and state constitutions.

"I think you could easily say Idaho is in the bottom 10 states [for public defense]," says David Carroll, executive director of the Sixth Amendment Center, who worked on the report.

The report found that the central problem with public defense in Idaho is that it's left up to its 44 counties. Each county determines how many attorneys to hire, how they're hired (sometimes prosecutors screen résumés), their caseload standard (if any), how much they're paid and if the service is contracted out. According to the report, counties such as Ada and Kootenai direct more resources toward public defense than their more rural counterparts, meaning the degree of justice a poor defendant receives is determined by county lines.

According to numbers presented to a legislative panel last year, there is one public defender for every 4,683 people in Idaho's First Judicial district, which encompasses Kootenai County and North Idaho, but only one public defender for every 11,611 people in the state's Seventh Judicial District in the northeast part of the state.

Public defenders also are outgunned. Results of a survey of 26 counties provided to lawmakers found that they spent a combined $22 million on prosecutors and only $14 million, or more than 36 percent less, on public defenders. Some counties spent three times as much on prosecution as defense.

"The counties don't know what's required of them, so they therefore fail," says Carroll. "It's easy to think of this as giving money to criminals rather than upholding our constitutional rights."

Morales says that another problem with Idaho's public defense system is the use of flat fee contracts. Although state lawmakers prohibited their use in 2013, 21 counties continue to contract out defense services to private attorneys for a set fee, regardless of the number or complexity of cases they are assigned. This arrangement, says Morales, gives attorneys a disincentive to spend time on public defense cases over more lucrative private work. Flat fee contracts are a particular problem with complex cases.

In 2005, brothers Matthew and James Wells were charged with murder in the killing of University of Idaho football player Eric McMillan. Charles Kovis, who was contracted by Latah County to serve as public defender, was appointed their lawyer. Kovis asked for a second lawyer to assist with the case, the norm with high-stakes charges. But Latah County commissioners balked at paying for another lawyer, even hiring an outside firm to block the county public defender from hiring help. A judge later ruled that the public defender could hire a second lawyer.

"It's almost like doing a brain operation with one doctor in the room," says Tim Gresback, a Moscow attorney who ended up working on the case.

The funding levels, says Morales, are also at the whims of county commissioners. Kovis served as public defender until 2013, when every county employee received a 4 percent raise, while his contract only saw a 2 percent increase.

"I have tons and tons of overhead," says Kovis of how underpaid he was under the contract. "Bottom line: I might as well have been a greeter at Walmart."

The ACLU lawsuit against the state of Idaho was filed on behalf of four individuals charged with crimes that it argues didn't have adequate defense. Among them:

Tracy Tucker of Sandpoint didn't have his public defender present at his initial court appearance in March. After that, according to the ACLU complaint, he spoke to his attorney a total of three times for a total of 20 minutes to discuss charges of attempted strangulation and domestic battery in the presence of a child. The court set his bail at $40,000. Unable to pay, he spent three months in the Bonner County Jail, according to the complaint, where he tried to reach his attorney 50 times before he pled guilty to attempted strangulation in June; he has been placed on probation.

Naomi Morley, another plaintiff in the ACLU complaint, was told by her lawyers that if she wanted an expert to challenge the state's allegations of drugs in her system following a car accident in Ada County in March of last year, she'd have to pay for it herself, according to the complaint. Morley, through her own efforts, obtained a sworn affidavit from another person acknowledging responsibility for the accident, according to the complaint, and her public defender was unable to investigate the vehicle involved in the accident before the state scrapped it, destroying evidence. According to the suit, Morley remained in the county jail with serious injuries from the accident for three weeks until her bail was reduced. Currently, Morley is on trial and facing 15 years in prison if convicted of all counts.

"If someone did commit a crime, it's likely the government will take their freedom away. Then it's especially important for them to have effective assistance of counsel," says the Idaho ACLU's Morales. "When we begin to pick and choose who gets effective counsel, then our system of justice is watered down."

After her trip to jail, Lisa Chesebro returns to her office. On the wall hangs a sign that reads, "Let me win. But if I cannot win, let me be brave in the attempt."

She has stacks of papers to go through. She has a felony trial she's worried about next week, meaning more work on evenings and weekends. She has a phone that rings constantly. She wakes up in the night thinking about motions she needs to file. Before heading out to her afternoon court hearings, she consoles a client who cries in her lobby.

The hardest part of her job, she says, are the cases where there's not much she can do.

"Sometimes the writing is on the wall, and it feels like no matter what efforts you put into it or what you're presenting to court [that], even if you'd done nothing, it'd be the same outcome," she says. "And sometimes it feels you're just a cog in the wheel; you're just slowing down the process but you're not changing what's going to happen, and sometimes that makes sense, but sometimes it's hard."

She recently had a case where a client was charged with attempted strangulation and battery. Despite the charges, she describes her client as a "really nice guy" who has no record and is seeking treatment. But the state, she says, won't cut a deal.

She also has victories, like the client who was falsely accused of rape and was exonerated because of her efforts. She makes about $57,000 annually and could make much more as a private attorney, but she says she'd miss the work.

Mayli Walsh, another Kootenai County public defender, says that part of her job requires standing in front of hostile crowds in courtrooms and defending the indefensible.

"I tell juries that soldiers don't go overseas and fight to make it easier for prosecutors," she says.

Morales says that the lawsuit the Idaho ACLU brought against the state is overdue.

"The state has been on notice for five years that its public defender system has been ineffective, disastrous, broke," he says, referencing the National Legal Aid & Defender Association report. "And for the last five years it's been kicking its responsibilities down the road."

The counties have indicated that they don't even want the responsibility. Last year, the Idaho Association of Counties passed a resolution stating that they didn't want the responsibility or cost of providing public defense, and called for the state to take it over.

"I'm glad they are suing the state," says Kootenai County Commissioner Dan Green of the ACLU. "I just want the standard [of how many lawyers to hire], so I'm following the U.S. Constitution, and I can tell the taxpayers that I'm being prudent with their dollars."

John Adams, the county's chief public defender who has a reputation as an aggressive lawyer, is always bargaining for more money, says Green, who adds that having a statewide caseload or funding standard would make these negotiations easier.

But over the past two years, Idaho lawmakers' efforts have been incremental. They passed bills establishing who is eligible for a public defender, requesting more study and not much else. They also voted against a bill that would have placed the public defender system under the purview of the state.

Earlier this year, the Idaho State Public Defense Commission issued a report finding that a significant barrier to more extensive reform was the lack of data on lawyer caseloads. The state is currently implementing the Odyssey computer system for the state judicial system, which would produce the needed data, but it won't be completed until 2017. (Across the border in Washington, the ACLU, beginning in 2005, began suing local jurisdictions, alleging that public defenders had such excessive caseloads that they were unable to provide adequate defense. In 2013, the state Supreme Court issued a ruling that established caseload standards.)

Meanwhile, the Idaho Prosecuting Attorneys Association has questioned the need for a sweeping overhaul. It called the conclusions of the National Legal Aid & Defender Association report "insulting and inflammatory" and has pointed to the organization's ties with controversial philanthropist George Soros.

"There are improvements that can be made," says Grant Loebs, a Twin Falls County prosecutor. "But I think to say it's unconstitutional is a spectacular statement without basis in fact."

Rep. Janet Trujillo, R-Idaho Falls, points to a more entrenched obstacle to reform.

"Public defense in Idaho is at the local level," says Trujillo. "And there are some that don't want to give up the possibility of that local control going away."

Chesebro ends her day by arguing to get a client, Lucas James, who has been charged with stealing a car, out on bail so he can receive mental health services while living with his mother, who tears up as she takes the stand.

"He's bipolar and extreme ADHD," she says, choking back tears as she tells the court that her son's support network is with her in Loon Lake, Washington.

"And if he were to reside with you in Loon Lake, Washington, are there services he can access to address those diagnoses?" asks Chesebro.

"Yes," she replies. "We just recently had him diagnosed."

Chesebro tells the court that James is doing well in jail. His medication is stable, and he's applying to mental health court.

"He wants to fast-track as much as possible his involvement, or hopeful involvement, in the mental health court," Chesebro tells Judge John Mitchell. "Knowing Lucas as long as I have now, I do believe that's a good program for him."

The prosecutor acknowledges that mental health is an important part of the case, but the defendant is too much of a risk to the public, which he says is the overriding concern.

Mitchell seems open to the idea of mental health court and would consider moving the sentencing hearing up if he's accepted.

"But for today," he says, "the motion is denied."

Chesebro packs up her stack of papers and chats with James' mother before walking out to the court's parking lot and climbing into her green Honda CR-V. She recently bought a house near a treatment program and sometimes sees her clients.

Although she's headed home for the day, her thoughts don't stray too far from work. Next week, she has a felony trial she has to prepare for on top of her other work, which will mean working on evenings and the weekend. She has to. With such a hefty load, everything could slip from her grasp. ♦