When state Sen. Andy Billig first ran for state representative back in 2010, he campaigned the old-fashioned way. Through winter snow and spring rain and summer heat, he knocked on door after door after door.

He started in March, and by the time November rolled around, he estimated he'd hit up 11,500 doors. By the end of it, he'd raised $133,000, mostly from individuals.

"I had more individual donors that any other elected candidate from the state," Billig recalls.

If Integrity Washington's Initiative 1464 passes this November, those small individual donors would become even more powerful. The initiative aims to push politicians to spend less time calling up rich donors, and more time trying to persuade average voters.

Initiative 1464 would give every voter three "democracy credits" — at $50 apiece — funded by closing a sales tax exemption for out-of-state residents. Voters wouldn't be able to use those credits for food or shopping — only for political donations to state House and Senate candidates who chose to participate in the program. If Billig participates, voters could go online and donate those credits to him, knowing it won't cost them a dime.

As a senator, Billig would be able to get up to $250,000 in democracy-credit funding alone, while state representatives would be capped at $150,000. In exchange, he'd only be able to collect $500 from each traditional individual donor, instead of $1,000.

Billig isn't yet sure if he'd take the option.

"I hope to," he says. "But I'll wait until I see the details of the rules before making a final decision."

The full initiative stretches 23 pages and is filled with complicated laws and rules intended to constrain lobbyists, restrict super PACs, increase the penalties for violations, bolster the state's underfunded Public Disclosure Commission, and increase transparency.

Ultimately, the fine print has left even Billig, one of the legislature's most passionate advocates for campaign finance reform, unsure if he'll vote to support it.

BIG MONEY, LITTLE MONEY

Spokane City Council President Ben Stuckart, however, is an unabashed supporter of the initiative. After having beers with initiative spokesman Peter McCollum — they bonded over both having debated for Gonzaga University — he opted to become a prime sponsor of the initiative.

"When I talk to people and the general public, their perception is that government is broken," Stuckart says. "We've got to fix that somehow."

That includes voters' perceptions of him. Stuckart says he bristles at how his critics often rush to assume that his votes on union issues are influenced by union donations.

"I just want to point out that the unions are all opposed to 1464," Stuckart proclaimed at a recent city council meeting. "As well as PACs, and as well as the business lobby. But the people are for campaign finance reform."

Yet I-1464 isn't exactly an underdog. As of last week, nearly half of the initiative's $2.6 million war chest had come from just three donors, each of whom had been born or married into vast sums of wealth.

Nearly a half-million dollars came from Jonathan Soros, son of liberal super-donor George Soros. Connie Ballmer, wife of former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, donated another half-million. New York's Sean Eldridge, husband of Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes, kicked in $275,000.

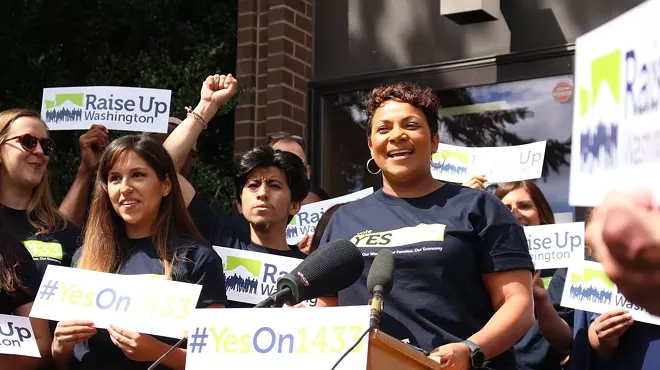

These three super-rich donors alone have given 54 times than the piddling $23,000 given to the political action committee opposing the initiative. For all the concerns about powerful interests, those interests — beyond state contractors and the food industry — have barely lifted a finger to stop this initiative. (Even the opposition's spokesperson, Yvette Ollada, is pulling double duty, also serving as spokesperson for the similarly outmatched campaign opposing Raise Up Washington's Initiative 1433, which would increase the state's minimum wage.)

Both McCollum and Stuckart say that they recognize the irony of an initiative intended to fix a system that "gives a wealthy few too much control of our government" being funded by wealthy elites.

"None of us are excited about big donors being able to swing elections with a single check," McCollum says. "[But] we would rather fight fire with fire."

Meanwhile, I-1464 is also intended to sap the power of lobbyists. Under the initiative, former legislators and senior staff would have to wait three years before becoming lobbyists or working for a lobbying firm. Lobbyists would only be able to donate a maximum of $100 per election to candidates who would oversee matters that impact them.

The same restriction would apply to certain potential government contractors — but not, the initiative clarifies, to unions.

But that, Ollada argues, gives unions an unfair advantage. Unions have just as much of a stake in legislative bargaining as contractors, but they would remain unrestricted.

"Exempting unions while restricting 'public contractors' will only strengthen their bargaining power over elected officials dependent on campaign contributions to get re-elected," Ollada says in an email.

Her biggest argument is the simplest one: The money raised by eliminating the out-of-state sales tax exemption could go to much better causes.

"If there are going to be more tax dollars raised, that should go to the first priorities of Washington, education and services, not to politicians and their political campaigns," Ollada says.

But Stuckart says that Washington governors have proposed closing the out-of-state tax loophole for more than a decade, only to see those proposals die time and time again in the Legislature.

"Right now the choice is, the tax loophole is still going to exist, or we close it and do this," Stuckart says. "I would rather have the common citizen have more influence on the system than the larger donors do now."

However, the way the initiative would shift the political landscape remains untested. While five states, including Oregon, already offer income tax credits, no state currently uses "democracy credits."

Seattle passed its own "democracy voucher" measure last year, thanks to a similarly well-funded campaign by similarly well-heeled donors. But that won't take effect until 2017. Plenty of questions remain. Would I-1464 get money out of politics or just dump more taxpayer money into it? Would it increase polarization or decrease it?

These unknowns are why Billig's Republican colleague, Sen. Michael Baumgartner, says he's intrigued by the democracy credit idea, but would rather another state try it first.

"I've seen several times when Washington state has intended to be a leader on national policies... and it hasn't gone well," Baumgartner says.

DARK AND GRAY

"Campaign funding is like water moving through rocks," Billig says. "As you block one path, it flows around and goes through another path."

For example, Washington already has transparency laws requiring political advertisements to list their top contributors. But PACs have found a way to sneak around that. Stuckart cites the example of a group pouring money into a recent state Senate race.

"They used a bunch of PAC names on the mailer. When you actually traced the money back, it was actually lobbyists out of Washington, D.C., calling themselves Citizens for Washington State," Stuckart says.

A recent Seattle Times story reported that one major donor — the innocent-sounding Working Families PAC — financed nearly $400,000 in attack ads against Issaquah Democratic Sen. Mark Mullet. Working Families was entirely funded by a PAC called the Leadership Council, which is in turn partly funded by something called the Strat PAC.

It's nicknamed "gray money": PACs donate to PACs that donate to PACs — making following the money trail almost impossible for the average person, obscuring the shadowy forces behind campaign ads. This initiative would change that, requiring campaigns to drill all the way down to find the big funders behind all those PACs and list them on the TV ads.

Yet this initiative wouldn't shine a light on another type of controversial campaign funding: dark money. In recent years, certain nonprofit groups have channeled unlimited sums into campaigns without being required to disclose their donors.

"In six states examined by the Brennan Center for Justice, dark money in 2014 was 38 times greater than in 2006!" Stuckart said at a recent city council meeting, reading from Governing magazine. "I shouldn't have to say much more, because we should get it all out of politics."

But I-1464 won't change that. In fact, two such nonprofits, Represent.Us and Every Voice, have donated nearly $715,000 to the 1464 campaign — though they disclose some donor information voluntarily.

The dark money oversight is the main reason that Billig's opinion on the initiative is so mixed. The intentions are good, he says, but it leaves a massive campaign finance problem unaddressed.

"It's a pretty large missed opportunity to add more transparency," says Billig.

The omission was intentional, McCollum says. He points to the way that Billig's bill to expose dark money was crushed by business lobbyists last year.

"If we had put it into the statewide initiative, we were told there would be significant money spent against us," McCollum says.

And then, suddenly, the opposition wouldn't be token anymore. McCollum alludes to the possibility that the Koch brothers — the big-money spenders on the libertarian right — would have brought their wealth to bear on the Washington race.

But that, Billig suggests, is exactly why the initiative should have tackled dark-money spending.

"If that's something that would get the opposition riled up," Billig says, "that tells you it was probably what needed to be addressed." ♦

I-735

As ambitious as I-1464 is in trying to change the campaign finance system, Washington's Initiative 735 is even more ambitious: It attempts to change the U.S. Constitution itself. In 2010, the Supreme Court's decision, sparked by a nonprofit being barred from advertising an anti-Hillary Clinton movie, ruled that the government couldn't restrict corporations, nonprofits or unions from independent expenditures during the election. In the years since, independent political spending has skyrocketed, and has gotten much of the blame.

I-735 would combat this by adding Washington to the number of states supporting amending the Constitution in several ways, including establishing that spending money doesn't count as speech and that constitutional rights only apply "to human beings."

Critics argue this would open the door to government censorship. After all, the New York Times and Fox News are corporations, and if they don't have free speech rights, what's stopping the government from cracking down on them? (DANIEL WALTERS)