Lori Halbig is waiting for his call. The man she loves is divorcing his wife, and tonight he plans to tell his soon-to-be ex about his intention to marry her instead. The whole thing is messy, but the 43-year-old Halbig can chalk it up to the whims of the heart.

Halbig, at the time a dispatcher at Washington Water Power in Spokane, is at work around 8 pm when Al O'Connor finally calls. O'Connor, the city's well-liked fire chief, says his talk with the wife went well, but his voice sounds unusually slow and weak. Halbig presses the phone up against her ear, trying to hear above the noise in the dispatch room, when she hears a click — like someone is listening in on the other line. It is March 2, 1981.

More than 30 years later, Halbig can still recount in vivid detail that fateful phone call — and the final words she'd ever hear from O'Connor.

"Honey, I can't wait until we're together all the time."

A few hours later, O'Connor will be dead, coffee-colored vomit staining the rug near his body.

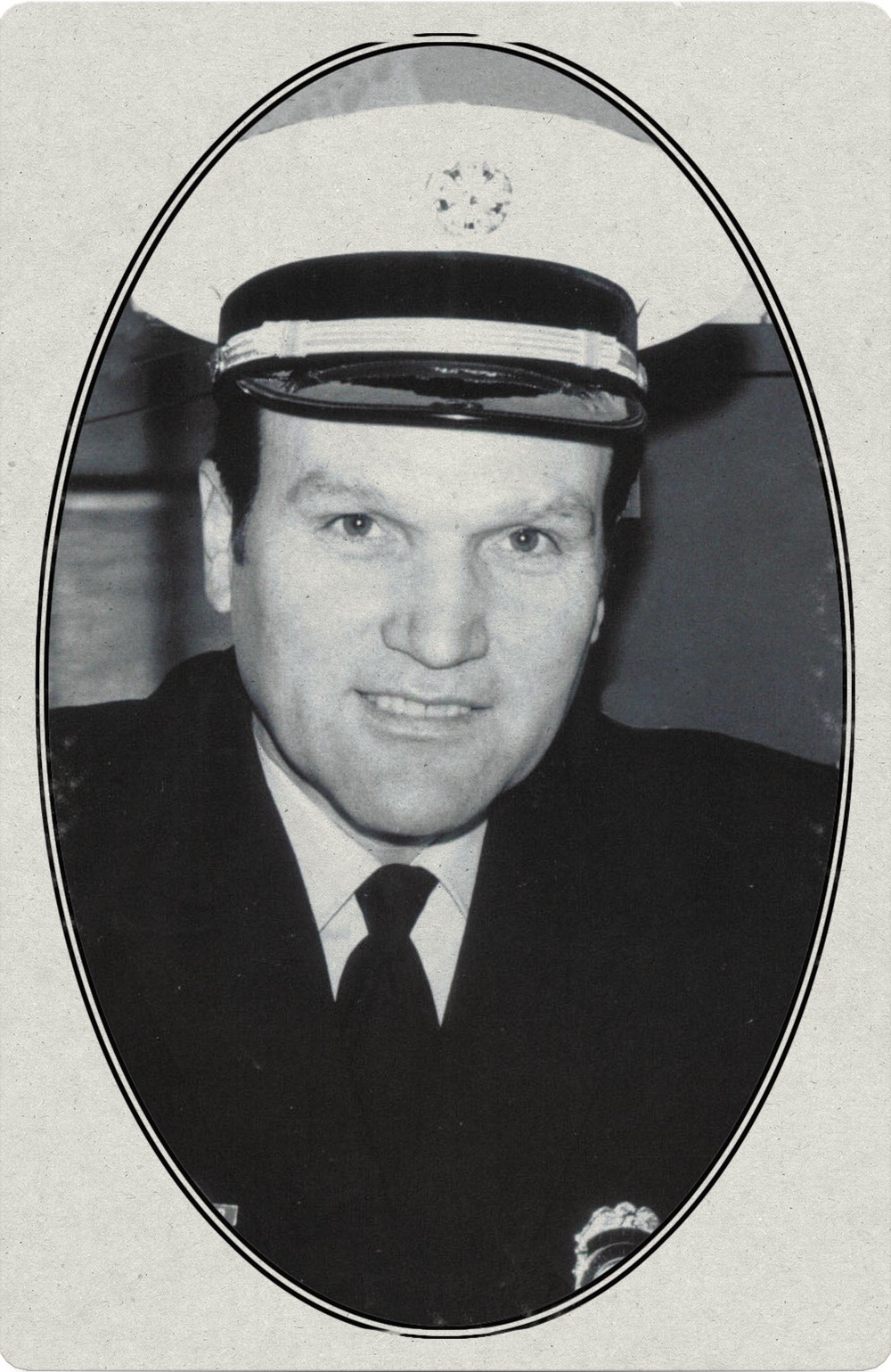

Alfred L. O'Connor joined the Spokane Fire Department in 1949 and climbed the ladder fast. On Jan. 1, 1972, at age 44, he became the youngest fire chief in Spokane history. He was known as a talented administrator who could repair anything in the fire station. O'Connor loved people and would weep openly at the loss of one of his men. He talked of running for mayor one day.

In April of 1977, Josephine, O'Connor's wife of 28 years and the mother of his children, died of cancer. A few months later, in the midst of grieving, O'Connor started seeing Linda Lipp, herself a recent widow. They married on Christmas Eve that same year — after dating less than three months — and O'Connor moved into Lipp's $425,000 house on 27th Avenue.

In some ways, the two were opposites. O'Connor preferred the company of people, while his new wife liked spending extravagant amounts of money on designer jewelry, clothing and high-end furniture. Their differences soon became clear to friends and coworkers.

"His wife was mentally cruel to him, ridiculed his profession and his association with the fire department," Janie Shoemaker, a close friend of O'Connor's, would later say. "He was a very, very unhappy and depressed man."

In January of 1981, O'Connor's outlook changed after Shoemaker introduced him to Lori Halbig, a soft-spoken policeman's widow. "They were like a couple of teenagers. He didn't try to hide. He was all over the city with her," Shoemaker would recall. Once the divorce to Linda was finalized, O'Connor and Halbig planned to get married that summer and buy a house on Spokane's South Hill.

"He was like the Al O'Connor I met the first time with his wife Jo," Shoemaker would say, according to a Spokesman-Review article at the time. "He told me that 'I love you. I love you very much. Because you introduced me to Lori and I love her. Al O'Connor's going to live again.'"

On March 3, 1981, at 4:05 am, Linda O'Connor calls the Spokane Fire Department alarm board. In a low-key voice, she tells the firemen:

"Oh, it's ... it's ... uh ... uh ... Mr. O'Connor ... I don't know ... he ... he ... he ... he drinks so much and just ... just ... out."

Minutes later, a fire truck and then an ambulance arrive on scene in a "tiered response" that O'Connor himself helped to pioneer. Firefighters find the chief on the floor of the den. He appears to have been dead for some time. There is dried, black vomit on the rug, walls and couch. His bladder had been emptied. Half a bottle of crème de cacao, a glass of water and two empty prescription bottles are found nearby.

Mrs. O'Connor is hysterical, wringing her hands, covering her face, tugging at her hair. "Is he OK? Is he OK?" she asks over and over, telling paramedics he'd been drinking all night.

Paramedics try to revive O'Connor and eventually load the 53-year-old in an ambulance and take him to Sacred Heart Hospital, arriving at 4:45 am. Half an hour later, O'Connor is officially pronounced dead.

Not long after, around 6 am, her husband just dead, Mrs. O'Connor begins to worry about the den where O'Connor fell over and vomited. According to police, a neighbor overhears her telling someone she needs to hire commercial cleaners.

After hearing the news, a distraught Halbig calls the city's police chief later that day and tells him of her suspicions — that O'Connor had been poisoned. She reports that a few days earlier, O'Connor had told her how he got violently ill, vomiting and falling over, after his wife served him grape juice in bed.

It doesn't take long before rumors of a "black widow" reach Spokane County Coroner Lois Shanks, who orders an autopsy on March 5. Unfortunately, by that point, O'Connor had already been embalmed — drained of blood that might have provided clues — but organ samples are recovered and sent to Seattle to be analyzed.

The death of O'Connor, adored throughout the community, is of particular interest to Patrick Lipp. His own father, Robert Lipp, had married Linda in 1971 and died suddenly in 1977. Like O'Connor, Robert Lipp had been contemplating a divorce from Linda at the time, and he too vomited before dying.

Before he died, Lipp's father also had rewritten his will, naming Linda as his sole beneficiary. Oddly, his signature on the new will didn't match his handwriting on other documents. Now, because of how O'Connor died, the Lipp family considers exhuming Robert Lipp's body.

Meanwhile, two police detectives are assigned to the O'Connor case and begin digging into Linda's past. They will soon learn that she was born Irmgard Boeker and that besides Lipp and O'Connor, she had two other husbands, whose whereabouts were unknown.

From the start, though, the detectives are instructed to tread lightly in the O'Connor case and would later recount that department brass, perhaps suspecting suicide, had told them to keep their investigation "simple."

Police Detective Brian Breen dresses up like a garbageman, riding a city truck along 27th Avenue. It is 10 days since the fire chief died, and Breen has a target in mind: the trash from the house the O'Connors shared.

In the garbage, Breen finds 17 empty Tranxene pill capsules, a prescription bottle filled with a watery mixture of Tranxene and Ativan and an empty half-gallon of MacNaughton's whiskey. (The state crime lab will later refuse to mix the two medications and whiskey for a test "because it was too dangerous." But a couple of police officers will sample the concoction on their own and report that they couldn't detect the drugs.)

Breen also discovers in the trash several handwritten notes, one of which he suspects was intended for Lori Halbig. The note reads: "A number of people have knowledge of your involvement with a married city official. Career-wise, this could hold severe ramifications for you and I am deeply concerned ... Please do not expose yourself to any unnecessary trauma which could be ruinous." It is signed: "A Good Friend."

Police return to the house about two weeks later with a search warrant and retrieve various documents, including notebooks, receipts and death certificates. During the search, they advise Mrs. O'Connor of her rights, and she tells them "I think I know what killed him." Then, without prompting, she repeats over and over "I didn't kill him," as many as 10 times, according to one officer's count.

On four occasions the detectives try to get a warrant to arrest Mrs. O'Connor, and each time Spokane County Prosecutor Donald Brockett turns them down. He tells the detectives he is waiting until the official cause of death is determined before making a decision.

When he died, O'Connor had seven different prescription drugs in his system — four of which had been prescribed to Mrs. O'Connor herself. Early on, Brockett had sought analysis from a toxicology expert in Utah who concluded there wasn't enough "medical certainty" that drugs caused O'Connor to die. But not everyone agreed. Two of the Northwest's leading pathologists concluded that the drugs indeed had contributed to his death.

Finally, after seven months of back and forth, Shanks, the first female coroner in state history, takes matters into her own hands. She calls for a coroner's inquest — a rarely used fact-finding proceeding that allows for hearsay. A date is set for December.

By the end of it all, Shanks' inquest will be called both a "circus" and a "travesty."

Fifty-six people are subpoenaed to testify. The controversy behind the fire chief's death had become one of the year's biggest local news stories, only eclipsed by the arrest of the "South Hill rapist." (Coincidentally, rapist Kevin Coe claimed he had visited the O'Connor residence as a realtor on March 1, two days before O'Connor's death. He said he had heard a "raving woman" screaming at the fire chief and wrote a letter to Brockett, the prosecutor, offering to testify.)

The weeklong inquest begins on Dec. 7, 1981, and from morning to night, one person after another is called to the stand — halted only occasionally when Lori Halbig or Linda O'Connor start sobbing and have to be led out of the packed courtroom.

Janie Shoemaker — the friend of O'Connor who introduced him to Halbig — testifies that Linda O'Connor threatened revenge if they divorced. "When he came to talk to me that day [in late December of 1980], he said his wife had said, 'If you divorce me, I will get your pension and I will ruin you in this city,'" according to a Spokesman-Review account.

Lori Halbig testifies that on March 1, two days before he died, O'Connor had told her he vomited, fell down and lost his vision after drinking grape juice from his wife. "I said, 'My God, Al, she's giving you something.'" The fire chief didn't believe it, telling Halbig: "No, she wouldn't do that. You know, I've painted a real bad picture of Linda. But she's trying hard."

Detective Brian Breen testifies that Linda O'Connor acquired 97 pills of Ativan tranquilizers over the course of March 1 and 2. She had two prescriptions that she "fraudulently" filled twice at two different pharmacies. He also says Mrs. O'Connor had waited before calling for paramedics, having first called her son for help an hour beforehand. (Toward the end of the inquest, the detective also files a written objection, accusing Brockett of acting more like a defense attorney for Mrs. O'Connor than a prosecutor seeking justice.)

Lots of doctors testify about the official cause of death. Having been unable to test O'Connor's blood, there is little agreement between them. Some pathologists conclude O'Connor died from the combination of drugs in his system. Others say blood clots ultimately did him in. And yet others say he may have suffocated on his vomit.

One person doesn't testify: Linda O'Connor, who had been subpoenaed by the jury but refused to take the stand.

In the end, the six-person jury deliberates for 15 hours. Their verdict creates only more confusion and suspicion. Four out of six jurors rule that the death was caused by both "natural and unnatural causes." Two jurors say that O'Connor died only of "natural causes." Three believe that Mrs. O'Connor had "occasioned the death by criminal means."

Because of the divided result, Brockett says he will not file any charges in the case. (A juror will later complain that they had not been told to reach a unanimous decision and they would have tried to do so if they had known.) Halbig and O'Connor's family write to Governor John Spellman asking him to take up the case, but the governor declines.

The following spring, however, at the urging of Detective Breen, prosecutors charge Mrs. O'Connor with two counts of obtaining a controlled substance by fraud. She pleads guilty and receives a year of probation and a $400 fine.

Linda O'Connor has never technically remarried. In the fall of 1981 — even before the inquest began — she met a younger man named Fran Austin. He eventually moves into the house on 27th Avenue, and O'Connor begins going by "Linda Austin." In June of 1990, the Austins buy a $211,000 condominium on Quail Ridge Circle near Manito Golf Course. They buy a homeowner's policy with Unigard Insurance Group that takes effect on Aug. 1, 1990. Less than three weeks later, before the Austins had even fully moved in, the house is vandalized, and the couple files a claim for $260,101.50 in damages and loss of use.

After a thorough investigation, Patrick Lowe, executive adjuster for Unigard, begins to doubt the validity of the claim. Lowe makes some calls and discovers that Mrs. O'Connor has filed an unusually high number of insurance claims between 1986 and 1990: 15 total. On April 29, 1987, she filed three claims with three different insurance companies for the same incident at a Paris airport. Mrs. O'Connor and her daughters had taken many shopping trips and were seemingly targeted by thieves a great deal. The "frequency of loss" and the fact that Mrs. O'Connor's "extravagant lifestyle" appeared to exceed her income ability are the first of many red flags in Lowe's findings.

Police Officer James Johnson, who is assigned to the case, also notices a number of irregularities. The vandal appears to have keys to both the front gate and the home. There are no signs of forced entry. Certain items are ignored, such as a painting of Mrs. O'Connor's daughter. The person who "broke in" apparently had brought their dog with them — similarly sized to Mrs. O'Connor's dog Higgins.

Unigard hires former FBI agent Robert Kessler to profile the person responsible for the destruction. He concludes that the vandal is a white female between 40 and 50 years old. She would be "extremely narcissistic," "self-centered," "have problems with interpersonal relationships" and "would probably have had experienced several divorces in her life."

When a lawyer for Unigard interviews Mrs. O'Connor about her former marriages in a deposition, she becomes upset and irritable, saying, "Let's just say I was married, numerous, several times" and that she was "not going to put up with the Spanish Inquisition."

Unigard refuses to pay, goes to trial in 1991 and wins the case.

For the most part, Mrs. O'Connor has avoided the spotlight for the past 20 years. In 2006, however, she appeared in a Spokesman-Review article in connection with her "husband" Fran. He had been accused of defrauding three elderly investors out of $96,000 and had been banned from selling securities. The article also mentioned that the Austins had filed for bankruptcy in 2005 and 2006 for having "more than $1 million in debt, including $94,000 in credit card charges."

Mrs. O'Connor, now 77, currently receives $5,288.97 a month from Al O'Connor's pension. According to the state Department of Retirement Systems, she has received more than $1.4 million over the past 33 years. The Austins now live in Western Washington, inside a large gated community at the Canterwood Golf & Country Club in Gig Harbor, in a gorgeous, two-story brick mini-mansion that retailed for $619,000 in 2011.

A knock on their door last month is answered by a stocky gray-haired man, who cracks the door open.

"Hello. What can I do for you?" he says in a friendly tone.

I ask if Linda is there and if he is Fran.

"Uh. What do you want?" he says.

"I'm doing an article on the coroner's inquest of 1981."

"Ohhh," he groans. "Not interested." And he shuts the door.

For his part, Donald Brockett, the former prosecutor, still believes there's not enough evidence to support criminal charges. "I am not interested in rehashing the case at this late date after 33 years has passed," he tells the Inlander by email. "There is no statute of limitations on murder. So if anyone feels the case should be brought, why hasn't the case been presented to prosecuting authorities with the new information?"

Lois Shanks, the coroner who publicly battled Brockett before calling for the inquest, died suddenly two years later, in 1983. A Chronicle editorial about her legacy cited the O'Connor case as well as her drive for truth. "Lois Shanks was a fearsome adversary of the suspected perpetrators; she would not rest until she felt police were conducting a satisfactory investigation; she wanted justice."

Detective Brian Breen, who has since retired from the department, considers the case solved, even though no one has been arrested. "There wasn't anything else ... that we could have done," he says of the police investigation. "It was obvious that the prosecutor wasn't going to charge the case."

Patrick Lipp, now a counselor in Spokane Valley, sees only frustration when he looks back on his father's death. "We all work under the assumption that the criminal justice system puts bad guys away," he says. "I'm frustrated with the system and how it can be manipulated."

Lori Halbig, even now, hasn't let go of Al O'Connor. She still wears the charm bracelet he gave her. She still has all the notes she took at the inquest and at the Unigard insurance trial. Halbig still lives in the region, and for 33 years she's kept a box of newspaper clippings and court documents. She hopes that someone will take up the case and find a use for all the evidence assembled by Spokane police.

Still in police custody, among the prescription bottles and empty pill capsules, is a Valentine's card that was found on the fire chief's desk — a gift from Halbig, which she hopes to one day get back. The envelope reads: "Happy 1st Valentines Day... "

"He was the only one that I felt I was supposed to be with," Halbig says. "I really loved Al O'Connor. He didn't deserve what happened to him. Al loved this city and there was so much more he wanted to do for Spokane. He was an exceptional man. He deserved justice." ♦

Acknowledgements: In addition to primary documents — including search warrants, witness statements, police records, autopsy reports and official correspondence — the 1981 archives of the Spokane Chronicle and Spokesman-Review were consulted in preparation of this article. So were local historian Tony Bamonte and journalist Bill Morlin, who covered the O’Connor case for the Chronicle.