You can hear the drumming from the front porch. In the living room of their Indian Trail home, James and Roberta Wilburn are sitting side-by-side, each playing a djembe, a wooden West African drum with a rich, distinctive sound. Roberta sets the pace with a basic beat — one hand slapping the skin of the drum in 4/4 time — before James jumps in, filling the spaces in the notes with riffs and syncopated rhythms.

It goes on for as long as it feels right, like a back-and-forth conversation without any words.

The Wilburns' practice session is part of the ongoing Heritage Arts Apprenticeships, a program co-sponsored by Humanities Washington and the Washington State Arts Commission. It provides funds for master-apprentice pairs within the state to explore a rare art form, often one that is misunderstood or threatening to become extinct, and study the cultural context that goes along with it. Now in its second year, the program has funded 25 yearlong apprenticeships, the Wilburns' being one of them.

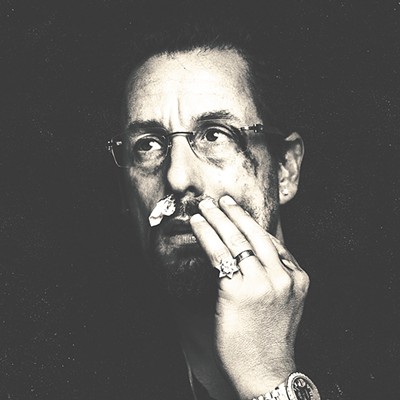

James is the "master" of the duo: A retired educator and former Spokane NAACP president, he's been drumming since he was a kid. Roberta, the associate dean of graduate studies in education and diversity initiatives at Whitworth University, is the "apprentice." The Wilburns have been married for 21 years, but Roberta says the most playing she had ever done was the occasional rat-a-tat-tat with her fingers on one of James' drums as she walked past it.

"I guess there was probably a little apprehension — that's his thing, not necessarily mine," she says. "But over the years I've heard him say, 'I want somebody else to be able to play with me.'"

Their apprenticeship has a key advantage: They live under the same roof, which makes the challenge of aligning schedules something of a non-issue. They started the program in July and will continue their lessons through this coming June, at which point Roberta will have picked up other instruments and more complex rhythms, and can perform alongside James in African drum circles, at an annual African-American graduation celebration and Kwanzaa.

But for the Wilburns, the apprenticeship is about much more than honing a skill: It's a means of connecting to their African roots, and educating others about the instrument's long, complicated history.

"When you think of Africa, you think of a drum," James says. "It's just part of the culture."

The Wilburns are one of 15 duos who have received grants this year — $4,000 for the masters, and $1,000 for the apprentices — which will go toward materials, equipment and any necessary travel expenses. The pairs apply for the grants with their self-imposed budgets and lesson plans, and a panel of experts determines the slate for the given year.

Langston Collin Wilkins, the director of the Center for Washington Cultural Traditions and head of the apprenticeship program, says the goal is for participants "to become stronger advocates for art and their general community." That means not only honing their respective crafts, but learning the business and time-management side of things so they can pass their knowledge on to others.

"Everyone applied with the hope they'd be able to preserve these traditions," Wilkins says, "and by funding them, we gave them the opportunity to dedicate serious time to preserving these traditions ... I think we're keeping the story of our communities and our state alive. Without these traditions, our understanding of our cultural landscape would be incomplete."

This year's apprenticeship concentrations include everything from stone carving to Salish wool weaving, henna body art to plant foraging, printmaking to hip-hop and spoken word. Last year, local culinary author Kate Lebo worked under the guidance of chef and teacher Lora Lea Misterly to learn all about farmhouse cheese making, a rare craft that she knew she could apply to her own writing.

"I'm always trying to find ways to combine culinary arts with literary arts," Lebo says. "I wanted to be there to see all the gestures, the things she doesn't think about when she does them. To have the attention and perspective of a master culinarian was really special."

As Lebo puts it, the apprenticeship program puts its focus on "arts that most people don't think of as arts." Not all of us have grandparents or parents that can pass down long-ago traditions that would otherwise be lost to time, she says, "so it gives structure to something if you don't necessarily have those family connections."

James Wilburn has always played to his own beat. He grew up in the Marion, Arkansas, hotel that his father owned in the years of Jim Crow, and he recalls being fascinated by the musicians traveling on the Southern "Chitlin' Circuit" who would stay the night there and sometimes even put on impromptu performances. He has played with countless musicians and has dabbled in every genre imaginable, but he didn't explore the sounds of West African drumming until relatively recently.

He has since taught African drumming to American students and played with groups in several African countries. What he tries to impart in his lessons is just how inextricably linked the drum is with African culture — how the instrument was used to send messages between villages. How those who were enslaved and brought to America took their drums with them. How the drums were then wrenched away when the slave owners realized it was a tool of communication. How African-Americans have since taken the drums back. How the drum is, essentially, the heartbeat that bridges multiple generations of people.

"Even in modern-day music, the drum is still communicating something," he says. "The drum is still talking to you."

The Wilburns, who also work as motivational speakers and social justice advocates through their company Wilburn & Associates, hope that they can continue that education once their apprenticeship is complete. The music itself is important to preserve, but so is the historical context surrounding it.

"The drum is something that was taken away from us, and so we're trying to incorporate it back into what we do," Roberta says.

"It's important that you know your heritage, where you came from," James says. "If you go back far enough, you can come up with a reason why you're here, as opposed to somewhere else." ♦