Thursday, July 13, 2017

Idaho's unemployment rate is unusually low — here's why

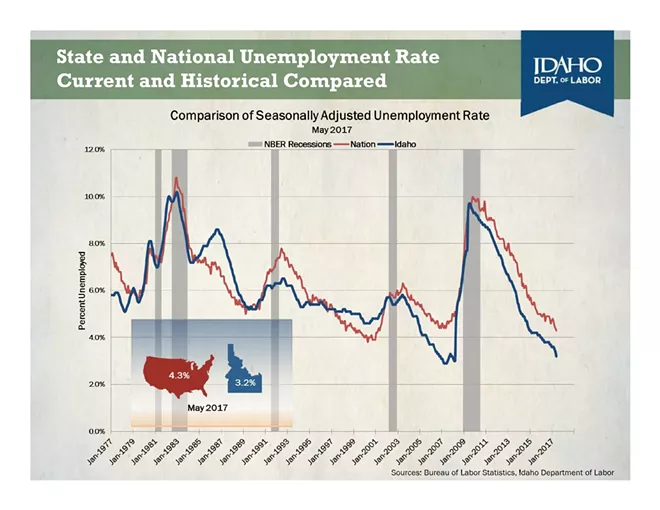

Idaho Department of Labor graphic

In the last few years, Idaho's unemployment rate has been dropping even faster than the national average.

Washington state has a lot to brag about. Most recently, it can brag about being chosen as the top business state in the nation for 2017 by CNBC.

But when it comes to low unemployment, Idaho has its neighbor to the west beat.

Idaho's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was a jaw-dropping 3.2 percent in May. Idaho has the 10th lowest unemployment rate in the nation, and it's two-tenths of a percent from being fourth-lowest. Washington? It's ranked 33rd, with its

Even looking at Spokane versus Coeur d'Alene, the difference is clear: Kootenai County is sitting at a respectable 4.1 percent, while Spokane County languishes at 5.1 percent.

The Inlander called up Sam Wolkenhauer, the state's northern regional economist for the Idaho Department of Labor, to understand why Idaho was doing so well.

Two words: Old people.

Idaho's natural beauty and low-cost of living, Wolkenhauer says, are driving retirees to move to Idaho, boosting other industries.

"We’re one of the top states every year. A lot of that has to do with property values; it’s a pretty affordable place to retire," he says. "It fuels demand of the service sector. The service sector for Idaho has really mopped up the excess labor here."

That represents a gradual shift in Idaho's economy, away from one dominated by manufacturing.

"For a long time, manufacturing was oversized in Idaho, and now the service sector is catching up," Wolkenhauer says.

Of course, not all jobs are created equal.

Compared with Washington, Idaho's wages have remained very low — the median household income in Idaho in 2015 was

"The source of strength [in Idaho] is the cost of housing and the natural amenities drawing people here to retire," Wolkenhauer says. "In Washington, the source of strength is going to be that it's wealthier."

A minimum-wage job, in other words, isn't as great as a six-figure job in the tech sector.

"We do have a fair share of growth in the minimum-wage jobs in the service sector," Wolkenhauer says. And in Washington, a minimum-wage job pays $11 an hour — in

But Idaho's low unemployment rate is slowly helping with its low wages, too. It's simple economics: If you have to fight tooth and nail to find workers, you're going to offer workers a better wage.

"When people are bidding on scarce resources, it drives the price up," Wolkenhauer says.

The recession hit Idaho later than much of the rest of the country, he says, and lingered longer. But after about 2013, the Idaho economy has been rapidly improving. Wages have followed suit, outpacing inflation. Compared to other low-wage states, Idaho ranks near the top for wage growth.

And even as the economy shifts toward more service jobs, other areas of the Idaho economy

are improving as well.

"We have a very healthy manufacturing sector here," Wolkenhauer says. "We’re one of the few states where manufacturing is growing."

That includes manufacturers in the aerospace industry, composite plastics, and food manufacturers like Chobani and Clif Bar.

Not every industry is bringing new jobs, however. Shoshone County, a very rural, low-population county (less than 13,000 residents) whose economy consists of mostly of timber and mining jobs, continues to struggle, with a 6.6 percent unemployment rate.

"The size means there’s no diversity in their economy," Wolkenhauer says. "When mining falls, the whole local economy suffers pretty significantly."

Not only that, but the timber industry has moved toward more automation. Demand increases and the mills make more money, but that doesn't mean more Idahoans are being hired.

"Lumber in north-central Idaho has been very strong in terms of board-feet produced," Wolkenhauer says. "It hasn’t translated to a lot of jobs. Those natural-resource-dependent communities are doing well in terms of their product, but it has not translated in terms of many jobs."

Like much of the country, the recession-era losses of construction jobs has reversed in Idaho, creating a whole new problem: There aren't enough construction workers for the jobs available.

"Construction actually has used up pretty much all the labor available," Wolkenhauer says. "All the tradesmen and construction workers are back to work."

If there aren't enough qualified workers in certain areas, employers have to look outside of the state to find employees.

"We rely on out-of-state labor for a lot of fields," Wolkenhauer says. "We’ve used up most of our available labor, especially skilled labor."

That's one reason why the low number of Idaho graduates who go on to college or technical schools worries the state so much. Despite the state's best efforts, the percent of students who continue their education one year after graduation fell to only 46 percent in 2015. So the jobs may continue to open up in Idaho — but many Idahoans will not be qualified to fill them.

"We don’t anticipate that employment will continue to grow," Wolkenhauer says.

Tags: Idaho , unemployment , economy , News , Image