On Jan. 6, 2021, an armed mob broke into the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., at the urging of the president of the United States. Whipped into a frenzy by the now-former President Trump's lies about a stolen election, these insurrectionists attacked law enforcement officers in a violent attempt to prevent the House of Representatives from certifying election results from the states. It was a dark day for our democratic republic that portends future violence from right-wing extremists in the years ahead.

In my last column, which appeared the day after the violence at the Capitol, I called upon Inland Northwesterners to "be like Washington" by getting themselves vaccinated against COVID-19. I hoped that 21st-century Americans could learn from George Washington's example by embracing an ambitious inoculation program like the one he pursued with the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

Trump's incitement of a mob to attack the Capitol reveals that he, too, could learn a lot from George Washington. While Trump encouraged his supporters to "fight" against Congress in 2021, Washington defended Congress from a potential coup from his officer corps in 1783.

Two years after the American victory over British forces at Yorktown in 1781, the Continental Army was camped outside New York City, keeping watch over the British garrison that remained there. Great Britain had largely ceased offensive operations on the North American mainland after Yorktown, but the war dragged on in the Caribbean and in Europe as France and Spain both hoped to dismember the British Empire.

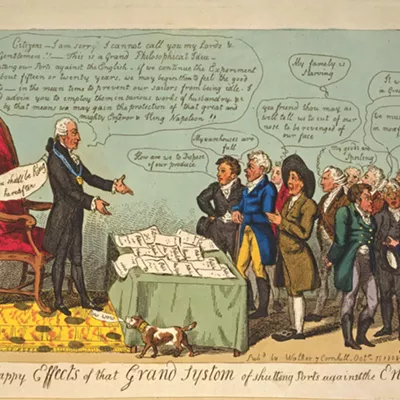

After eight long years of war, the soldiers of the Continental Army had time to look to the future in their camp in Newburgh, New York. And in doing so, a growing number of officers grew increasingly resentful over Congress's broken promises, which included mounting back pay and inaction on veterans' pensions. Earlier petitions had failed to bring about any government action, and by 1783 passions were rising. Encouraged by some shadowy members of Congress, a cabal of officers urged the army to present an ultimatum to Congress. The exact nature of this "ultimatum" is unclear, but the officers planned to threaten some form of extralegal action against the government of the United States.

If Washington had wanted to become king, or a dictator, now was his chance. He could have mobilized the discontent of the Continental Army to advance his private ambition. Instead, the general performed a master class in political theater to uphold the rule of law, no matter Congress's shabby treatment of his officers and men. Washington arrived unexpectedly at a meeting of the discontented officers to persuade them of their folly. With a written address in hand, the 51-year-old general took a pair of glasses from his pocket, noting "Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country." Many officers were moved to tears by Washington's eloquent display of the price he had paid for service to his country. This simple act helped to defuse the tense atmosphere of the meeting, and the officers heeded the entreaty of their commander-in-chief to remain loyal to Congress.

Shortly after defusing the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy, Washington resigned his commission in the Continental Army. Washington's yielding of power earned him the respect of even his archenemy, King George III. When told that Washington intended to return to retire to private life, the British King commented, "If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world."

The contrast between our first and 45th presidents could not be clearer. While our 45th president ignited a powder keg of resentment that he himself had helped to fill with his lies about systematic electoral fraud in 2021, George Washington helped to defuse an attempted coup against Congress in 1783. When both had the opportunity to mobilize an insurrection against our elected representatives, Trump's narcissistic pursuit of power at any price threatened the survival of our democracy; Washington's selfless dedication to public service meant that he surrendered power to save our fledgling republic.

To celebrate Washington for not installing himself as a dictator in 1783 is, in many ways, faint praise. It is the very least that we should expect more from our military and political leaders. Nevertheless, despite his many flaws — Washington was an ambitious man who was used to wielding absolute power over the enslaved community on his plantation of Mount Vernon — the first president was a committed public servant. But if there is one thing that we learned about Trump during his tumultuous presidency, it is that he was never able to transcend his innumerable character failings. ♦

Lawrence B.A. Hatter is an award-winning author and associate professor of early American history at Washington State University. These views are his own and do not reflect those of WSU.