On May 1, 1977, about 1,200 people gathered on a street in Spokane to do something that wasn't all that common in those days — run a race through a city's downtown. In fact, it was unique to be running at all in 1977, but the inaugural Lilac Bloomsday Run helped change that. Within a matter of years, the race became a national event, attracting the world's top distance runners. By 1996, it featured more than 61,000 participants.

As athletes lace up for the 40th running of the race on Sunday, we look back at how Don Kardong, a Seattle-bred, Stanford-educated Olympic marathoner, took a simple idea and, with the help of an eager community, turned it into a cultural touchstone for the Inland Northwest. Kardong had come to the region during college and the years immediately after to work at Camp Reed, at the suggestion of his college teammate, Spokane native Steve Jones (now Bloomsday president). He fell in love with the region, trained for the 1976 Olympics here while teaching sixth grade, and returned to Spokane after his fourth-place marathon finish in Montreal.

In early 1977, he found himself not running a race, but creating one from the ground up. Here's how we got Bloomsday.

TRACY WALTERS, a longtime, nationally recognized Spokane high school track coach and former director of Camp Reed who trained Kardong for the 1976 Olympics. Walters went onto serve as the finish line announcer for more than 30 years: "[Don] was living with us at the time and he went down to the Peachtree run in Atlanta. He came back and he said, 'You know, Coach, road running is becoming a big deal. We ought to do something in Spokane.'"

KARDONG: "I told a newspaper reporter that I thought we should have a downtown run here in Spokane. That was a time when it was really rare. But I'd seen a few here and there. There was a little run down to Bowl and Pitcher, and after that she asked me what I thought about all this interest in running in Spokane. I said it was good, but that we needed a downtown run. I didn't intend to actually organize one. But then it was the accidental meeting of getting on the elevator in City Hall with the mayor, and he said, 'Well, I read what you said in the newspaper.'"

WALTERS: "So in a few weeks, Don made a presentation to folks at the city. He knocked the ball right over the centerfield wall. Then [former Spokane Police Chief] Bob Panther says, 'Whoa, whoa, whoa. We can't do that. Why would you shut down the roads on a Sunday?'"

KARDONG: "It was very tough for city officials, and I don't blame them. The police and traffic engineer were not thrilled with this idea because when there were road races in those days, they were away from downtown. They were out in the country. Closing down streets for a run was a new idea."

WALTERS: "I remember that Mayor Rodgers said, 'Bob, do you remember where I grew up?'"

MAYOR DAVE RODGERS (from Kardong's book Bloomsday: A City of Motion: "You know, I remember growing up in Boston and going down to the corner with Mom and Dad every year on Patriots' Day to watch the Boston Marathon go by."

KARDONG: "Everyone said that if the mayor is behind it, then OK. We'll do it.'... Ron Richardson was also on the elevator with me [when he encountered Mayor Rodgers]. He was an acquaintance of mine and was with the Spokane Jaycees. He thought the Jaycees could maybe help out."

KEN HILL, then-president of the Spokane Jaycees, formerly the Junior Chamber of Commerce: "The Spokane chapter of the Jaycees was pretty strong. We had about 135 members at that time — a bunch of young, enthusiastic guys. Don said, 'I envision about 300 runners, perhaps.' So we budgeted a thousand bucks."

JERRY McGINN, a Spokane UPI bureau chief who was recruited for the first Bloomsday board: "We held meetings all over town in the early days. Many of them were at my house. The meeting sometimes went on so long, and were so uninteresting to me, that I went to bed, and those still there would turn out the lights before they left."

HILL: "The remarkable thing was, we're talking January, early February [when the Jaycees first met Kardong] and the race date was May 1.

DOUG KELLEY, a member of the Jaycees who became the Bloomsday co-chair with Kardong: "If you go back and look at the entry form for the first Bloomsday, it says limited to the first 500 runners, because we thought it was smart marketing and that people would rush to sign up."

WALTERS: "We knew kind of what we wanted to do, but we weren't sure if anyone was going to show up."

KELLEY: "Once the entry form was out there, it was going to go off. We made a lot of dumb little mistakes, not really knowing and understanding what we were getting into."

KARDONG: "I was still teaching school during the day. I'd get a call at the school from the guys and have to walk down to the office and answer a question about how to do something."

During the winter of early 1977, the logistics of Bloomsday fell into place. The race was publicized all over town and beyond, and the number of entries began to grow. A T-shirt was designed. Dr. Ed Rockwell joined up to help with aid stations. A timing system was developed. But they still needed a course. What no one knew yet was that Kardong had plans to make the run a tribute to one of his favorite novels — James Joyce's Ulysses, a book that reimagines Homer's Odyssey as a single day in 1904 Dublin. Literary scholars call the day depicted in the book Bloomsday, after its protagonist Leopold Bloom.

KARDONG: "I was looking for a course that was between 6 and 9 miles, because it was a distance that was challenging, but no so long that most people would say, 'Well, I can't go that far.' I looked for routes all over, but there's not that much that looked like a really good course."

DAN LEAHY, Kardong's high school cross-country teammate, who became the Bloomsday founder's running partner as he tried to develop a course for the race: "We started going out on runs to scout a course. I can remember four or five of them. And from the beginning, [Kardong] was very particular that the places in the course matched the places in Ulysses."

KARDONG: "I thought it was such a clever book. In college, a teammate of mine was an English major and had a strong connection to that. We'd talk about what we could see while we were running that fit into that book."

LEAHY: "Before a run, he'd say, 'So I think I've got a course picked out.' And I'd think, 'Oh, this ought to be good.' [The potential courses] were tough physically, but they were fun in terms of the way he was thinking about how someone who would be running up the Monroe Street hill, and how that related to the book. I remember him pointing to a gas station that had a one-eyed owl and saying, 'There's the Cyclops,' and going past the police station and Don saying, 'There's the sirens.'"

KARDONG: "Well, once you have the course, you can tie in anything to the book."

LEAHY: "I came to learn that going on long runs sucks, but going on long runs with Don is enjoyable."

They eventually settled on a course that began on Riverside Street in downtown Spokane, crossed the Maple Street Bridge and continued to West Central before coming back to Riverfront Park.

KARDONG: "Ken [Hill] liked the name "Nat and Back" because we were going to Natatorium Park and then back downtown. But I guess I had the right to name it. At a meeting they asked what we were going to call it and I said, 'I want to name it the Lilac Bloomsday Run.' It was dead silence in the room.

HILL: "Don explained the name Bloomsday, and it sounded kind of weird."

KARDONG: "Ken asked, 'Whatever happened to Nat and Back?' I still don't think that would have worked."

Bloomsday was coming into existence at a time when running for exercise was still in its infancy. Olympic distance runners like Steve Prefontaine and Frank Shorter — the former Kardong's college rival, the latter his teammate — had captivated the nation in the early 1970s. Doctors were realizing that cardiovascular health was important, and running could help build it. Still, you didn't see a lot of runners out and about. This was part of the reason that organizers expected only between 300 and 500 runners.

WALTERS: "Folks figured if you were out running on the streets, you must be a criminal running away from something. But gradually it became more acceptable."

KARDONG: "It was a different time. When I was training [for the Olympics] in Spokane, I remember people yelling at me from their cars as they went by... They just wanted to harass someone doing something different, I guess."

HILL: "About a month before the race was held, I said, 'Well, hey, I think I'm going to run.' So I went out and ran the first mile and I didn't die. Next time I ran a couple of miles and thought, 'Well, that wasn't too bad.' Basically, I started training for the race, which changed my life for the better, as it did for thousands and thousands of others in Spokane."

KARDONG: "I thought big community races were a good concept because it was a sport where as an average athlete, you could compete with the best people in the world. That was unusual. You can't do that in any other sport."

JON STEELER, a then second-year Gonzaga law student who ran: "I was running 2 or 3 miles, maybe, at the time. This 8-mile thing was going to be at the top of my limit."

LORINDA TRAVIS, a retired postmaster who ran the first Bloomsday as a 21-year-old Eastern Washington student and has run every race since: "I don't remember a lot of people running back in the 1970s, or getting ready for Bloomsday. But after the first Bloomsday, you could always find someone who would train with you. It just caught on."

STEELER: "I don't think I had like, real, live running shoes. I had basketball shoes for intramural basketball — like, Converse or something. I'm 23 or 24 years old. What did I know? But my feet hurt so bad after [Bloomsday] I went and bought my first pair of Nikes."

CAROLYN BRYAN, a Spokane mother who ran the race on a dare from her daughter and continued to run for decades thereafter (from a previous Inlander story): "I had no clue what I was doing. I went to the shoe store and bought what I thought were running shoes. I mean, they were like boats; I think they weighed, like, 2 pounds each. I didn't even own a pair of shorts, so I borrowed a pair of my husband's old gym shorts. I'm sure I was a sight, but fortunately no one took my picture."[2]

WALTERS: "We realized early on that if people want to do Bloomsday, we ought to provide a program for people to do clinics, for people to increase their mileage."

After months of scrambling, the Bloomsday committee arrived at Race Day. The 1,200 runners who materialized on that Sunday afternoon exceeded anyone's expectations. The streets were closed, the course marked, and Olympic gold medalist Frank Shorter was ready to run, as was Joan Ullyot, a top female runner who was already blazing trails as an authority on running's effects on the body. And in a region where the first of May could easily bring spring snow or driving rain, it was sunny and warm... a shocking 81 degrees. At 1:30 pm, the racers, some more experienced than others, took off. At the front of the pack was none other than Don Kardong.

KELLEY: "We were all amazed by how many people had come out for this."

KARDONG: "The weirdest thing we did that first year is that someone convinced us that we should all meet ahead of time on the steps in front of the floating stage for a photo. We had 1,200 people sitting there. And Frank [Shorter] goes by and he says, 'Doesn't anybody warm up?' We had a procession from there to the starting line. We never did that again."

WALTERS: "I was at the starting line and started them off, then had to head to the park to the finish line to help there. It was a bit of a mad dash."

"SUNSHINE" SHELLY MONAHAN, a Spokane radio and television legend who got her start at 18 years old, driving a Volkswagen Rabbit around town as part of a promotion for radio station KJRB: "With everyone in the community knowing about Sunshine Shelly, and to look for that KJRB car... Don Kardong asked me to be the lead car in the first three Bloomsday races. As you can imagine, I was beyond thrilled and honored."

HILL: "I just remember this euphoria. It was 1,200 people running, and it was the first time I'd ever been running in a crowd like that. It was just exhilarating. There would be people I knew who'd come zipping by me, and I'd say hello and think, 'I didn't even know they were a runner.'"

KARDONG: "I was really excited when the first race started. To be charging down Riverside at the head of that big group. It's like a big idea that finally gets put into reality. It was tremendously exciting to get it all together. When I ran across the Maple Street Bridge it was still a toll bridge. I remember the big smiles the toll takers had. They were ready for it, but I think they were just really amused to see the bridge being used that way. I led all the way across the bridge and then Frank [Shorter] passed me. And then after that, Herm Atkins out of Seattle passed me."

After finishing third in the inaugural Bloomsday, distracted along the course by things he noticed were out of place or not running quite as efficiently as he'd hoped, Kardong and others noticed that the effects of the unseasonably warm weather were taking a toll.

TRAVIS: "I remember being very grateful that people had hoses that they sprayed into the road and got people wet."

KARDONG: "At 1:30 in the afternoon it was 82 degrees. And nobody was heat-trained because it was early May. And even if you get a moderately warm day that early, people won't be ready for it."

DR. BILL PETERS, a Spokane physician and avid runner (from a previous Inlander story): "Coming in [to the finish line], there were still people laying around the course [having collapsed from heatstroke], and I and my best friend got together and helped out, getting IVs going. But I never got my T-shirt because I was busy helping out."

KARDONG: "I'd never seen heatstroke before. I remember finishing and standing around and all these people were collapsing. They were OK, but it was frightening."

HILL: "Some of us, when we finished at the old Forestry Pavilion in the park, this tiny little place, a few of us had run and then started helping at the finish line, passing out T-shirts and sandwiches. That was kind of weird."

KELLEY: "We're doing a run on hot day and then serving hot sandwiches to the runners once they were done. I remember thinking, 'This makes no sense.'"

KARDONG: "One thing I was pleased with, looking back, was that there were as many women as there were. I think about a quarter of that first Bloomsday were women, which was a new thing. A lot of the women who ran in that first Bloomsday were really pioneers for women's running in our area."

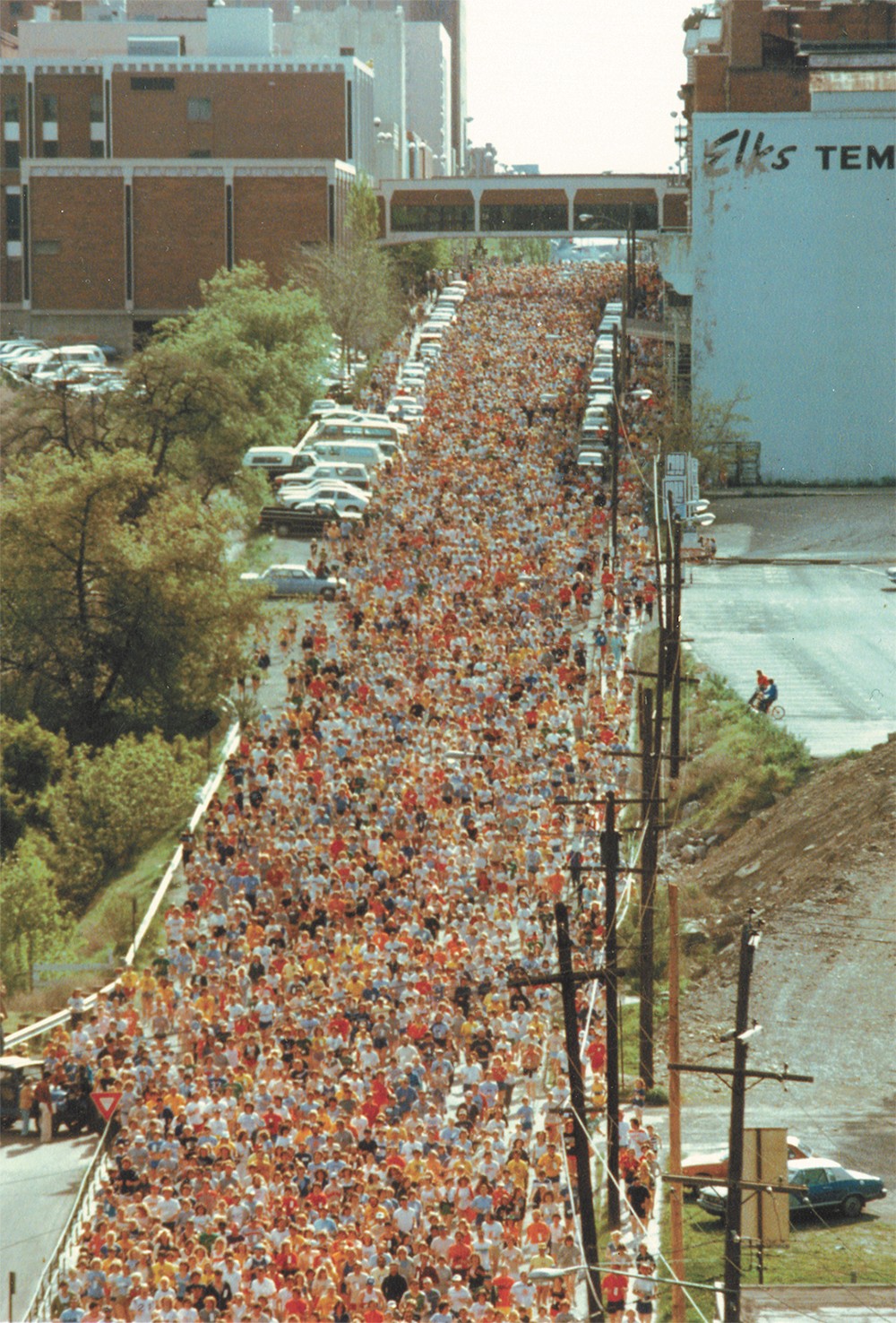

In the years that followed, Bloomsday grew at a pace that few expected. The second running drew about 5,000 participants. By the mid-1980s, there were more than 50,000 runners, quickly attracting the attention of the running world and bringing in more and more of the world's best distance runners. Bloomsday also became ingrained in the culture of Spokane.

KELLEY: "I know how it changed my life, and I can imagine how many other peoples' quality of life has improved because of Bloomsday."

WALTERS: "Over the years, one of the things I've seen that I love the most is the families who come back every year and use Bloomsday like a reunion. You see them out running the course together."

MONAHAN: "To again be the celebrity starter for the 40th Bloomsday is something I hold near and dear to my heart. Spokane is the most precious place to be born and raised, with amazing people who truly look after each other. Bloomsday is Spokane. Don has given his heart and soul, and it will always be considered 'his' race."

LEAHY: "Don has a way of painting a picture or telling a story of what might be possible. He has a way of continuing to spin the yarn. In one way, I'm not surprised that it's turned out this way, that it became one of the biggest races on the planet, because he continues to unfold that story." ♦

RUNNING SHOES IN 1977

As you'll read in this history, some of the runners who took to the first Bloomsday starting line weren't properly equipped. With recreational running still in a nascent stage, it wasn't common to have a set of running shoes in your closet. At this time, though, running shoes were coming onto the market, and not just for elite runners. The industry standard for several years was considered to be the Adidas SL 72, after which many other shoes were modeled. In 1975, Nike's Waffle Trainers became a popular, lightweight shoe, designed — and heavily mythologized — by Oregon track coach Bill Bowerman, who poured rubber onto a waffle iron to create the distinctive tread pattern. By the third Bloomsday in 1979, "air" technology had arrived with the Nike Tailwind, one of the most popular running shoes of all time. (MB)

BLOOMSDAY'S FIRST CHAMPION

In 1977, there wasn't a bigger name in U.S. distance running than FRANK SHORTER. And when Don Kardong, who had run with Shorter on the U.S. Olympic team the year prior, recruited the marathoner to run in the inaugural Bloomsday, the race's slogan — "Run With the Stars" — was not an overstatement. Shorter had won the gold medal in the marathon at the 1972 Munich Olympics and the silver at the 1976 Games in Montreal, finishing two spots ahead of Kardong.

For the inaugural Bloomsday, he gave a clinic to the area's runners the night before the race, which he won with a time of 38:26.

"Frank had all that charisma to get out in front of people and do presentations. He was also a good-looking, handsome, gifted athlete," says Tracy Walters, the longtime U.S. Track and Field coach who also enjoyed a long, successful high school coaching career in Spokane.

Shorter went on to co-found the Bolder Boulder 10K race in his hometown of Boulder, Colorado, in 1979. (MB)

THE 40TH LILAC BLOOMSDAY RUN

Sunday, May 1, 2016

APPROXIMATE START TIMES

9 am: Elite, Corporate Cup & Brown

9:05-9:15: Yellow & Green

9:15-9:45: Orange & Blue

9:45-10:05: Lilac

10:10 (approximately): Red

TRADE SHOW and LATE REGISTRATION: If you haven't registered yet at bloomsdayrun.org, you can still sign up for the race at the Bloomsday Trade Show at the Spokane Convention Center (334 W. Spokane Falls Blvd.) on Friday (11:30 am to 8 pm) and Saturday (9 am to 6:30 pm). Late registration is $35 per person, including tax.

The same days and hours apply for runner check-in and the trade show itself, which features running gear for sale as well as other fitness-related vendors.

MARMOT MARCH: This year's kids' Marmot March, held at 9 am on Saturday at Riverfront Park, already is sold out. No entries will be taken the day of the event. Those already registered can pick up their T-shirt and number at the Bloomsday Trade Show.