My father brought his good friend, Don, back to life. It was a dark country night. The only thing lit for miles was Don’s trailer out past Woodville. My father walked up to the trailer and knocked. Don’s wife let him in. She held their adopted baby in her arms as she wept, covering the baby in tears, which is not like water from the lake but the water from the bottom of the ocean. Deep dark tears that could drown the baby if she wasn’t careful. There were others there, the Misfits, as my father referred to them. Cross-eyed toothless misfits. They were happy to see my father. They all grinned at him in unison, like one giant idiot.

Don’s body was in his room lying dead on his bed. Face up. Which is when my father recalled his deal with Don. Don died of a serious cancer that took him hard and fast. But in the time he had after the diagnosis and the actual dying he called my father from his work, a salesman at the local John Deere store, and asked him if he would raise him from the dead.

“Like Lazarus?” asked my father.

“You’d be Jesus,” said Don.

My father didn’t respond right away and since Don had Carhartt bait just walk in the conversation ended.

After work Don stopped over our place.

“How was work t-day, Don?”

“How yah feelin’ t-day, Don?” “Yah lookin’ tired t-day, Don.”

Without getting too cute about it all Don asked again if my father would raise him from the dead as soon as he could. “As fast as you can make it out to my place,” said Don.

My father was a little panicked and really had nothing to say but felt some sort of response was necessary and what he came up with happened to be the present question on his mind. “Before the body starts rottin’, Don? “I just don’t want to be too far gone. I know it’s gonna feel too good the further up I go.”

“OK. I’ll do it,” said my father. Just like that.

So there was my father looking down at his old pal, Don. Dead as can be. He checked for breathing and even looked where the pulse goes on a man’s neck.

Part of him considered this a possible legendary joke at his expense. He wouldn’t put it past Don to come up with something this good. So he put his hand on the man’s heart. Nothing still. He couldn’t believe someone could die. People die every day. He knew that. Everyone knows that. He had people in his life die. His parents for one. His little brother even. But this was something, seeing a good pal like Don just laying there, perfectly still.

The Misfits came into the room and stared at my father. They still held those idiot grins but what other expression could you expect from this bunch? Talk about your absolute lowlifes, the group looked like one big food stamp run through the dryer multiple times.

First my father whispered, “Rise up.” But really no one could hear it and the body didn’t move. Don at this point was on the other side sitting on the second step of a long stairwell, head in hands waiting for my father to get on with it. Don could feel the light and warmth on his back. No sounds just the cold darkness below and the warm white light above. My father said it again, “Hey yah, Don. Rise up.” That got Don’s attention. Don stood up wanting nothing more than to climb the staircase but felt bad about making my father go through all of this. But he didn’t realize how good death would be. “A week,” Don said to himself. “I’ll go back for one week.” So, Don stepped back into his earthly body and sat up.

Once he was fully back he heard the Misfits giggle and snort and wriggle about his bedroom. He looked at my father, gave him a pat on the shoulder and said, “Thanks, man.”

My father was a little taken aback. He almost felt like Don should have stayed dead because well, isn’t that the way this world works?

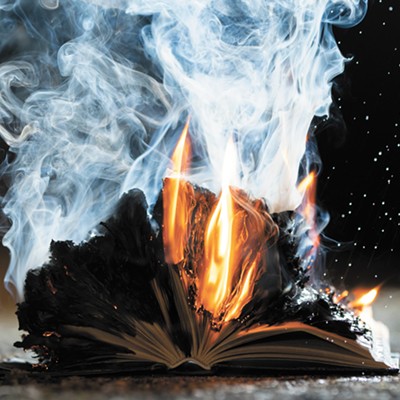

Anyway, Don told my father that it’d only be a week and to not tell his wife about it, “It’d only make her cry and I don’t want the baby to suffer the rain.” He also told my father to observe him as much as he could during this week, he had wisdom only a person come from the other side could attain. My father knew it to be true and cleared his work week and told us that he’d see us in about seven days. Which was fine for us. Me and my sisters were older and really didn’t have much to do at home. We had our stuff. I had baseball. My older sister, Nicole, had her job at Rod’s Big M, the grocery store, and my little sister, Christine, painted nearly all day and night. My mother cooked and spent the remainder of the day dusting off the old books in our attic. She liked taking care of those old hard covers. Both my parents understood that opening an old book written by a dead author is like opening a bee’s nest. “You have to do it ever so slightly,” they would warn us over and over again.

Growing up in that old house I did my best to stay away from all those books. Every once in awhile I’d pick one up and peak inside, doing what I could to not disturb the sentences. Only once did I open one too wide feeling an instant rush spring forth. Like a cold wind from some other place and time. I shut the book but the damage had already been done. That devil was forever free.

Don didn’t know about books like us but he knew his John Deere mowers and trimmers and riding green machines. He went back to work. He came home and held his daughter and set her on the hardwood floor and picked up his steel guitar and plugged it into the amplifier and jammed right there for her. My father by his side the whole time soaking in Don’s presence. “Wisdom doesn’t come from me telling you anything, Rene.”

“Then why am I following you around, Don?”

“It’s in the way that you use it,” sang Don as he struck the cords and moved further into tune. “It’s in the way that you use it.” And right then the baby rolled over for the first time. “Boy don’t you know whoawhoa.”

“What is that supposed to mean?” asked my father. “Listen to me and watch my baby roll.”

My father did exactly that for a while (getting nothing out of it) until Don’s wife said dinner was ready. Three separate piles of Hamburger Helper on the kitchen table (like three mini-landfills) all ready to go. They ate and afterwards Don told my father to look after the girl as he led his wife into their bedroom. My father watched as Don’s little girl rolled from one room to the next knocking into the coffee table and some dining room chairs. Not crying but baby-laughing every time her head went thud against the durable furniture.

By midweek Don didn’t look too good and his wife began to shed heavy tears three times a day. “Don’t let her drown the baby,” said Don. “After I die would you please watch over both of them until she runs dry?”

My father agreed, anything, anything for his best pal in the world.

It was not hard for my father because he loved Don’s little girl. One day he admitted to us that none of us were ever like this one. “Only a few in history are like this one,” he’d say. “Once every thousand years.” My sisters and I had our things when we were barely old enough to walk. Christine colored her walls with crayons and India ink she found in an old desk drawer. Nicole set up lemonade stands, even in the rain she had business moving under her small umbrella, the bums would come with their crummy change. It apparently went well with cheap vodka. As for me I was nothing but baseball. Stats, cards, memorabilia. “This one,” my father said pointing at Don’s baby, “will grow as big as an oak and her shadow will cast itself over all of us, even spread north covering Lake Ontario.”

Don died for the second time on his seventh day back on earth. He immediately sprinted up the stairs and split through the gates in a beam of white light.

His wife finally stopped crying one day and released my father from her and the baby’s care. He came back to us and my mother was relieved because she had so many homemade raviolis in the freezer that needed to be eaten. That night we all made it over to the old house to see each other and catch up. It was a celebratory occasion. Nicole ate 15 raviolis. Christine had 12. Mom and dad both ate 10 each. And I ate the most at 27. While we ate dad told us all about Don. He wanted to make sure Don’s existence lingered on earth for a little while longer. He recalled him as a John Deere salesman, the best one. “But he never did end up giving me one of those hats. I always wanted one of those green hats.”

“The books are dusted,” said my mother.

My father smiled and leaned over and gave her a big smackeroo on the lips. Nicole told us about her day and about a woman she had to fire at Rod’s Big M, “She was stealing pints of Ben and Jerry’s every day for lunch. She got fat, too.”

Christine took out a folded piece of paper from her back pocket and unfolded it for us. It was a perfect sketch of Don playing his steel guitar. My father took it and framed it. It’s sitting on their mantle to this day.

As for me I had nothing interesting to say. I only had baseball on the mind and really there’s nothing that interesting about baseball. But they wanted to hear me talk nonetheless. So I went into detail about Ted Williams. His picture-perfect swing and how the man was a war hero in the prime of his career and how I so wish God still made men like Ted Williams. But God makes a different sort of man these days. Like Don once said, “More like dogs with disjointed hips.”

As for Don’s baby, she grew up fast and one day came back to the North Country to see everyone and to speak at the old Mennonite church in Woodville. The entire village showed up. Her mother too, very old and still with that puddle in her eye. We filled the building and sat down in those hard wooden pews they don’t make anymore. We remained in a state of high hope, our bodies on the verge of a great quake, waiting for her to take the pulpit.

About J.P. Vallieres

J.P. Vallieres lives in North Idaho with his wife and three sons. His most recent and forthcoming works have been and will be published in Grey magazine, Rock and Ice magazine, Adirondack Explorer, North American Review, and Spoke, a new Inland Northwest literary review. He is also working as a FedEx delivery driver for this holiday season.

About the Contest

The 56 entries we received this year represent a record for our fiction contest. Either the theme — debt — weighed heavily on people’s minds or the unemployment rate just left a lot of aspiring writers with nothing to do but write. Either way, the submissions this year were strong, in addition to being numerous. These stories — about the things that break people, the things that heal them, and some very obedient fleas, among other things — are our favorites.

— Luke Baumgarten, Section Editor