"Shh, I'm concentrating," the artist says.

I've asked James Frye why he uses these colors in his work, why he chooses the neon lime and red and hot pink and puts them side by side. It's hard for him to explain his ability to hear colors, how exactly the sounds compute in his brain. His mother, Wendy Frye, says the neurological phenomenon is called synesthesia; it also means he has perfect pitch.

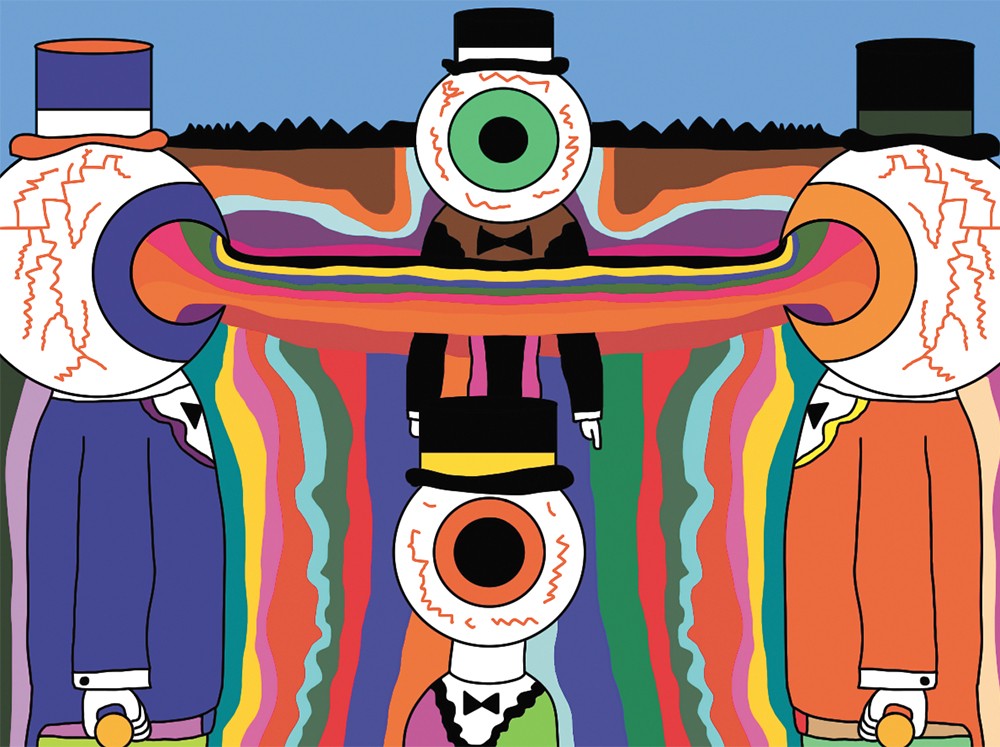

Last week, sitting in front of a giant Mac screen in his parents' Spokane Valley basement, the graphic artist demonstrates his drawing technique employing a stylus and electronic Bamboo sketch tablet. His own secret soundtrack blares in his headphones as he turns thick black lines into an oval eye shape and fills it in with kaleidoscope hues. He shows me his other fascinating works, too — many of them available online and now also at 4000 Holes record store, one of his favorite places in town, in poster and print form.

"Do you like this one?" he asks of every piece.

"Yes," I say, because I do.

His drawings are full of cats and humans and eyeballs. The images are deeply psychedelic and include checkered landscapes.

Later, his mother says he's never shown anyone his process before. James makes art late at night when everyone else is asleep. He'll wake his parents at 9 am, wanting to share what he's created. He makes art about once a month; the rest of the time he's ruminating.

James was diagnosed with autism at 3 and didn't talk until he was 8 years old. Now at 22, and the size of a football lineman (6-foot-5 and 280 pounds), James opens up about the future.

"I want to make money to get out of this place," he says, in a stilted voice. "I want to have my own animation company."

He also explains his idea for a 3-D hand-drawing program he hasn't yet invented.

This is a lot of insight from a man who so often doesn't discuss his feelings. One time, when James was saying rude things, and his mom was tired, she told him he was being a jerk.

"Enough," he said.

It's a word he often uses when he's done with a conversation. It's a family-coined "James-ism."

This is what it's like having a son on the autism spectrum.

Two weeks ago, a bee got into the house. It buzzed around James' head, and as he's allergic to bees, he panicked. His parents were at work, his 20-year-old brother Jon was in class at Eastern Washington University. James called his mother, who raced over. She found him hidden in his upstairs room, doors shut, closet hangers everywhere (his chosen insect-killing weapon), dogs barking.

These are the types of situations that medical cannabis (pills and topical creams, mostly) helps with. It softens James' anxiety.

"Dan and I are still married. 27 years," Wendy says of her husband, today at her dining room table. "Many couples don't stay that way. This isn't easy, but I refuse to say, 'Poor me.'"

When the doctors diagnosed James, Dan and Wendy had never heard the term. Now, according to the National Autism Association, one in 68 children in the U.S. are affected by the disability, and boys are four times more likely to be diagnosed.

James went to public school, and progressed slowly. But at Central Valley High School, which he'd later graduate from, he started art classes. Eventually, this would lead to gallery shows around Spokane, and a preference for graphic art — it's less messy.

"To be honest, when someone says their autistic child makes art, I think of finger paintings," Wendy says. "I applaud those other artists, too, and the parents who support them, but James is so unique."

Her house is full of James' art. From his early pottery to his squiggly-lined Jackson Pollock-phase paintings. Now his art has evolved into something all his own; it's not a copy.

Although still in the early stages, multiple studies have shown the positive effects art can have on people with autism. A 2004 study in Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association found that "art therapy for autistic children may serve as a path toward increased awareness of the self."

And certainly, Wendy sees those effects in her son. Through his drawings, he has blossomed. Wendy, who works the business end of James' art, admits that she wants to share her son's talent.

"He's an artist, who also happens to have autism," she says. "He is that good. I want his work in every nook and cranny possible."

James' father Dan has an entire room devoted to the Beatles. Lunchboxes, posters, music in all formats, including crates of vinyl. Since James was a baby, he's gone to record stores with Dan. That tradition continues now. Last month, the pair even went to Seattle to dig for music.

Today, James shows off his own record collection, including the Monkees box set he just bought. James listens to music constantly in this basement den, especially anything from the 1960s, like the Beatles and Rolling Stones and the Who. Moog synthesizer moves him. Sometimes while listening to psychedelic rock, he'll shout and he'll jump, behavior called stimming. The constant motion has hurt his left leg, which bears the brunt of his weight. As loud as he blasts his records, he can't go to a live concert without getting physically ill from the commotion of people and noise. Yet these sounds show themselves in his work.

4000 Holes owner Bob Gallagher is especially impressed with James' drawings.

"What I see in his art is attractive, bright colors and interesting objects," he says. "I'm not an artist and I can't really judge it, but there's a connection there to music that's so easily seen."

Last year, We Are Lions, an organization that highlights artists with disabilities, selected James to create a poster for rock act My Morning Jacket. It was his first commissioned piece, and his family wasn't sure he'd agree to doing it. But after listening to their music incessantly, he created his own version of the band's The Waterfall album cover. The group printed 200 copies, signed them and sold them through We Are Lions, with proceeds going to James.

"They promoted him as an emerging artist," Wendy says. "We couldn't be more happy."

Today, James sits silently in front of the record player as Hot Butter's "Popcorn" spins slowly.

"What are are you thinking about?" I ask.

"Concentrating," he says.

His mother soon moves to the door.

"Are you ready for us to leave?" she asks.

"Enough," he says. ♦

Find James Frye's art at 4000 Holes — Record Store and jamesfryeartist.com.