Spokane's own rule against sitting or lying down in public in downtown includes exceptions for when shelter space is unavailable, but while proponents say it helps keep downtown safer, opponents have said it criminalizes homelessness.

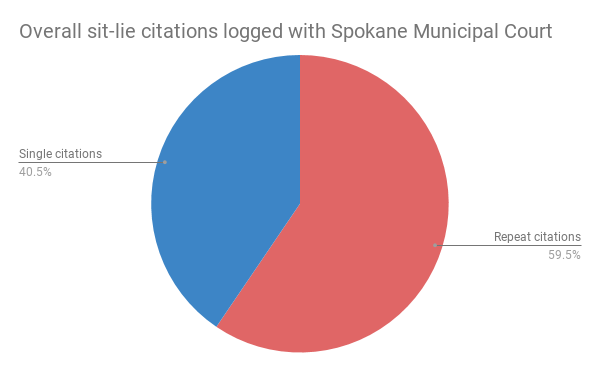

Since 2014, when enforcement of the December 2013 ordinance started, there have been 395 sit-lie citations logged with Spokane Municipal Court that went to 240 different people.

More than half of those citations were issued this year alone.

Between Jan. 1, 2018, and now, there have been more than 200 sit-lie citations, according to a search of court records conducted on Sept. 13.

That's already more than double the total for all of 2017, when 91 sit-lie citations were recorded with the court, and double the amount of citations issued in 2014, 2015 and 2016 combined.

One reason for the recent increase is that downtown police have started using the ordinance more as a tool to get people into community court, where the hope is they'll get connected with service providers on site, says Spokane Police Lt. Steve Braun, who works in the downtown precinct.

"If we can use this a little bit more and get more people into community court, we can hopefully get more of them into services and get them off the street," Braun says, "so they can live a better life and get more what they deserve as human beings."

The decision to start using the tool more often throughout 2017 and 2018 came after discussions with Braun and other leaders at the downtown precinct about an apparent increase in downtown homelessness, he says.

"It appears there’s more individuals experiencing homelessness in the downtown core than there has been the past," Braun says. "There's also great service providers. We talked about what can we do as a police department to connect them."

The majority of people cited over the last four years only received one citation, with about a third receiving two or more. Sometimes people were cited again within a day or a couple days, while other repeat citations were spread out over months, and in just a few cases, over years.

About 60 percent of all citations issued went to the people who received more than one.

Still, among those who were cited more than once, only a small percentage received more than two or three, with 15 people receiving four or more. At the high end, one person was cited nine times, and another was cited 12 times.

Similar ordinances prohibiting sitting, sleeping, or lying on public property have come into question in recent years, as highlighted most recently by a decision out of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals this month that held Boise cannot enforce its similar policy on nights when shelter space is not available.

The court held that while cities aren't required to provide shelter space, if there is no space available that doesn't require participation in a religious program, prosecuting people for behaviors tied to living violates the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the Eighth Amendment.

"Any 'conduct at issue here is involuntary and inseparable from status — they are one and the same, given that human beings are biologically compelled to rest, whether

by sitting, lying or sleeping,'" the majority of the panel wrote, quoting a previous opinion.

But Spokane officials are confident the city's policy, which is only enforced in the downtown core, doesn't run up against the issues in that ruling.

Spokane City Attorney Mike Ormsby says the ordinance is not enforced when shelter space is unavailable, and police are given daily updates from service providers who run shelters in the city so they know how much space is available.

"Citing people is a last resort. Both the Police Department and others in the city have tried to refer people to services," Ormsby says. "If there is not room for someone in a shelter then the Police Department will not be issuing citations."

Typically, when officers approach someone who is violating the rule for the first time, they will explain that the rule exists, offer to direct them to services they may need, tell them areas where people are allowed to hang out during the day and issue a warning, Braun says.

Those who do receive sit-lie citations are referred to community court, where people are sent to deal with low-level city violations and get connected with service providers. If people follow that program, they can frequently get their charges and fees dropped, Braun says.

For police in the downtown core, outreach is a big part of what they do, which includes building relationships with business owners as well as homeless individuals, he says.

"Our purpose is never to punish somebody. We’re never targeting one demographic: We’re looking at the behavior of the individual, not the individual themselves," Braun says. "Specifically with sit and lie, we use that to get the person into community court so they can get in touch with services. Nobody deserves to be homeless."

The goal is to incentivize them to get the help they may need, whether that's for addiction, mental health or any other issue, Braun says.

In some instances, Braun says speaking hypothetically, officers may ignore other low-level crimes like say, smoking marijuana, and simply issue a citation under the sit-lie rule, in order to incentivize that person to go to community court. The hope is to get them into whatever program they need to be in to end their homelessness, he says.

"Again, the hope with all that stuff is to end the criminal behavior, not criminalizing the individual," Braun says.