The clock in the kitchen read 5:05 am, but it was already more than 100 degrees outside — the early summer sun crowding a midday sky over Orofino, Idaho.

“I keep the clock set to Guam time — 16 hours ahead of us,” whispers Adelia Anderson (everyone calls her Sue). “It’s already tomorrow there.”

Maybe, just maybe, she says, Guam’s tomorrow might bring today’s truth — if not the full truth, well, maybe a piece of the truth. Anything would help.

Sue and her husband, Chris Anderson, remember their first phone call to Guam: sometime in early January 2011, when they called their daughter Kelsey to see how she was settling into her new South Pacific assignment at Andersen Air Force Base.

“That’s when we first set the clock to Guam time,” says Sue, cracking a half-smile. “We didn’t want to wake her up with a phone call if she was sleeping.”

Five months after her assignment began, USAF Airman First Class Kelsey Anderson was found dead by Andersen Air Force Base personnel, shot with her own service pistol while on duty as a security officer in the early morning hours of June 9, 2011.

The Andersons have lost count of the phone calls they have made to Guam since Kelsey’s death. In each call — sometimes in sorrow, other times in anger — they continued to ask anyone who would listen:

“What happened at the scene of the shooting?”

“Why did it take so long to send Kelsey’s body back home?”

“Why didn’t all of Kelsey’s belongings return to her family?”

“Why were Air Force personnel ordered not to talk to us?”

“They told us she killed herself. She shot herself in the head,” says Sue, “but there was no note, nothing. And she was on duty. And get this, she was scheduled to come for a monthlong break in just a few more weeks.”

Sue takes a moment to compose herself but to no avail.

“I’m sorry. … I should be over this now,” she says and sobs.

In a series of tear-stained interviews, Chris and Sue Anderson tell the story of how their little piece of Idaho heaven — living peacefully along the Clearwater River, about 40 miles east of Lewiston, with two great kids — has devolved into a hellish battle with the United States government.

At best, the U.S. Air Force has disrespected the Andersons in refusing to be forthcoming about their daughter’s death, which recently marked a grim second anniversary. But at worst, the debacle reeks of a cover-up that has resulted in a precedent-setting lawsuit against the U.S. government.

The Andersons were hoping it wouldn’t have to come to this: They’re listing the U.S. Air Force as a defendant with summonses appearing on the doorsteps of the U.S. Attorney General and the U.S. Attorney for the District of Idaho.

I sat with the Andersons in their Orofino home as the soft-spoken couple tried to make sense of what happened to their youngest of two children. A few feet away sat a brass box with the emblem of the U.S. Air Force emblazoned on the outside, and the ashes of their 19-year-old daughter on the inside.

The Nicest, Sweetest, Toughest Girl You Ever Saw

The Andersons say they built their home for their two children — Kelsey and brother Max (two years older, now 23). Sitting on a gorgeous piece of North Central Idaho overlooking the river, Kelsey would usually be seen atop one of the family’s five horses — her favorite was Shorty — while Max was usually found riding ATVs or snowmobiles.

Lately, Max spends most of his days away from home as a lineman, assigned to assist regions throughout the country that have been hit by natural disasters. His parents say he keeps most of his thoughts to himself.

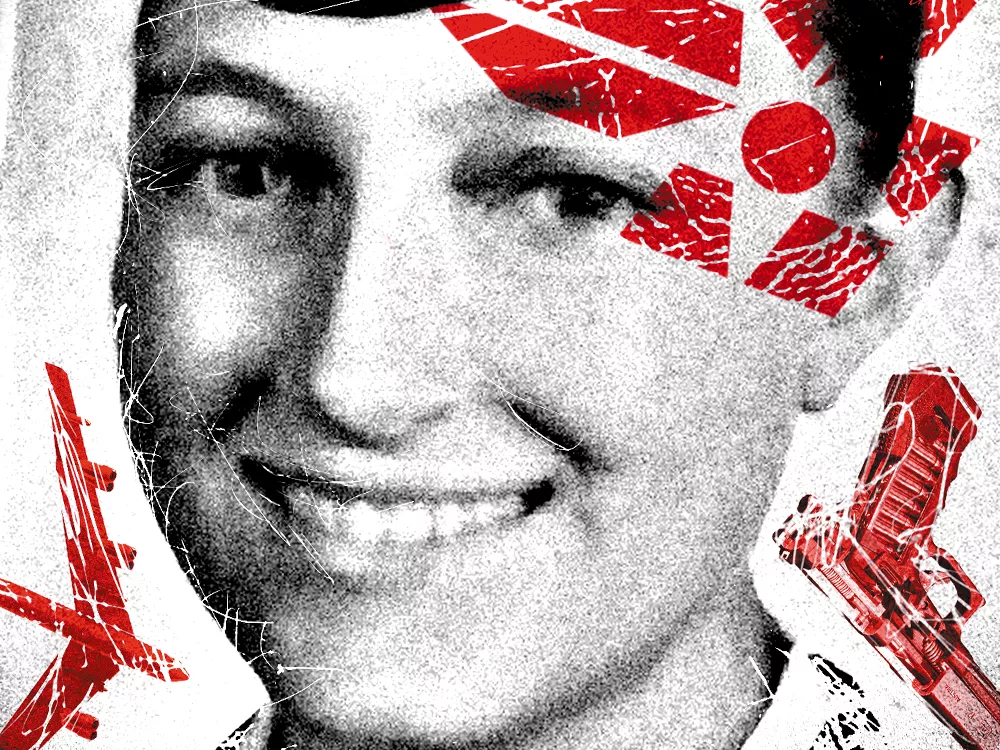

And now the Anderson home is filled with photographs and memories. A hallway-full of class photos portray Kelsey from kindergarten through high school — prettier and prettier still, her hair growing longer, her smile stretching wider (except for that one year when she had braces).

“When we open her bedroom door, I want you to take a big breath,” Sue says. “I don’t know what it is, but it still smells so fresh in there, so lovely, just like her.”

Kelsey’s bedroom appears as if she were expected to arrive at any moment: her clothes, jewelry, makeup all where they should be, walls filled with pictures and posters and a sign that reads, “I live in a house, but I’m at home in a saddle.” Her shelves are stacked with triumphs: medals, ribbons and trophies for horseback riding, tap dancing, piano, but mostly soccer.

Once, Kelsey’s junior-high soccer coach cautioned her team — comprised of both boys and girls because the school wasn’t big enough for two separate squads — that they would need to “play more physical” against an all-boys team. “What do you mean, play more physical?” Kelsey asked her coach. But in short order, Kelsey “smacked into the boys and took the ball away,” coach Ken Lame recalls, adding that Kelsey turned to him, with a big smile, and said, “I’m going to like this.”

“She was the nicest, sweetest, most tender-hearted, toughest, meanest girl you ever saw on the soccer field,” Lame says.

Lame’s words were met with laughter and tears June 18, 2011, the day of Kelsey’s memorial. Kelsey’s jersey, No. 12, was officially retired, as many of her former teammates wore their soccer gear and played a pick-up game following the memorial.

“I think a lot of the kids are still trying to get over her loss. We hug when we see each other in town,” Sue says. “One of her friends had the words ‘Live in the Moment’ tattooed on her arm, along with Kelsey’s birthday, the day she died and Kelsey’s initials.”

Much of Orofino came out to remember Kelsey at the memorial service, but an especial pall was cast over the ceremony: Kelsey’s body was still half a world away. Her body’s absence would be one of many mysteries still unanswered since the day the Air Force told the Andersons that their daughter had died a violent death.

“Sue was up at our hunting camp that day [June 9, 2011]. She was cooking for a bunch of hunters that had just come in,” Chris says.

The Andersons, semi-retired from a well-pump installation business, still run an outfitting operation on the North Fork of the Clearwater River for elk, deer, bear and cougar hunting seasons.

“I was working in the garden at home that day, and I saw a big black car, with government plates coming up the driveway with an escort from the Orofino police,” Chris says. “A full colonel got out. He wouldn’t even tell me that Kelsey had died face to face. He handed me a piece of paper and said, ‘Read this.’”

The letter, delivered by USAF Lt. Col. Theodore Unzicker and signed by the USAF Maj. Gen. Alfred Stewart read, in part:

Dear Mr. And Mrs. Chris A. Anderson,

On behalf of the Chief of Staff, United States Air Force, I regret to inform you of the untimely death of your daughter, Airman First Class Kelsey S. Anderson. … According to appearances and initial evidence as reported by Andersen Air Force Base officials, she died from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound. While further details are unavailable at this time, you will receive a letter from your daughter’s commander, which will provide additional circumstances.

But that second letter never came. In fact, the Andersons have, time and again, tried to ask about the “additional circumstances” surrounding Kelsey’s death. And two years later, their questions have mounted to the degree that they are suing to find the truth.

Hangar No. 1

“Kelsey’s Hotmail and Facebook passwords were changed June 9, 2011, and her computer, cellphone and personal items were immediately taken for evidence,” Sue wrote in her detailed notes to Spokane attorney Matt Crotty, who is representing the Andersons in their attempt to read the investigation file on Kelsey’s death.

The Andersons say that first of all, they were anxious to have their daughter’s body back home, but were repeatedly told that Kelsey’s remains would be kept in Guam for additional forensic examinations.

“The town of Orofino was in shock and we had the services scheduled for June 18. We had a lot of young kids who needed to get over this,” Sue says. “But they kept telling us that they needed to keep Kelsey’s body. And Kelsey’s body didn’t arrive at the Seattle airport until June 21 and she got here on June 22.”

The Andersons were still in shock. They had only put their daughter on a plane to Guam on Jan. 2, 2011, following an extended Christmas break in Orofino.

“When she graduated from high school in 2010, she said she wanted to see a bit of the world so she talked to an Air Force recruiter. She did magnificently at basic training in San Antonio, and when she graduated from boot camp, she was the proudest person you’ve ever seen,” Sue says. “We had a wonderful Christmas together and she left for Guam on Jan. 2.”

The Andersons say they communicated regularly with Kelsey, via email and phone calls, during her five months in Guam.

“I spoke to her officer in command and she said, ‘If everyone was like Kelsey, we wouldn’t have any problems in the service,’” Sue recalls. “They even determined that she was a candidate to become a Command Post specialist. The Air Force even sent agents here to Orofino to interview all of her family and friends so that she would be eligible for top clearance, but that never happened.”

The Andersons say they pieced together a scenario surrounding their daughter’s death through a series of conversations with USAF Special Agent Jason Larsen and Maj. Sarah Babbitt, Kelsey’s unit commander.

“Sometimes they wouldn’t tell me until I was hysterical,” Sue says.

At approximately 6:30 am, on June 9, 2011, Kelsey was wrapping up an overnight security shift, which included her check of a building known only as Hangar No. 1, which houses B-2 bombers, and which is supposed to be staffed by two security officers. Kelsey reportedly requested, via radio, to go to the bathroom on an upper floor of the hangar. A short time later, Kelsey was discovered slumped in a bathroom stall with a gunshot wound to the head. The stall had been locked.

The Andersons say that in a conversation following the incident, Larsen told them “there was no or very little gun residue” on Kelsey’s hand and that her service pistol had been sent to the Office of Special Investigations for ballistic testing. Kelsey’s personal belongings, including her smartphone and laptop, were also taken as evidence.

For the next several months, the Andersons repeatedly called officials in Guam for more information, but were told that the investigation was still pending and that there was little to be shared.

On Sept. 24, 2011, some of Kelsey’s belongings, including her clothes, shoes and makeup, were delivered to the Andersons’ Orofino home, but her phone, laptop, wallet, driver’s license, debit and credit cards were missing. When they inquired about the missing items, the Andersons said they were told that the remaining items would be returned after the case was closed by OSI.

The Andersons continued to call Guam for answers but were told either there was nothing that anyone could tell them or that the investigation was still under way. It wasn’t until July 2012 that the Andersons were finally notified that Kelsey’s smartphone, laptop and wallet would be sent back to Idaho. They were to be shipped to Mountain Home Air Force Base, southeast of Boise, and driven up to Orofino.

“I said, ‘No, this time we’ll come get it.’ But they said, ‘We don’t want you on the base.’ They told us to meet them outside of the base,” Chris recalls. “So two plainclothes, armed guys show up in a Walmart parking lot outside of the Mountain Home Air Force Base, hand me a box, have me sign a piece of paper and drive off.”

When they got home, the Andersons discovered that the smartphone had been locked and remains locked to this day. Kelsey’s laptop had “very few files on it,” according to Sue, “And the only photographs left were these tiny little images that you could never enlarge. It just doesn’t look right.”

The Andersons Find Two Advocates

Through much of their frustration, the Andersons say they found an advocate and friend in Bernie Fritz, a casualty assistance representative at Fairchild Air Force Base.

“When the Air Force loses a member, there are certain reporting and notification procedures that have to be followed,” said Fritz. “It’s my job that they be done properly and the notification to the family is done timely, humanely and expeditiously.”

Fritz was very reluctant to talk about the case.

“You can ask your questions; that doesn’t mean I’ll answer,” he says.

But the Andersons say Fritz stepped in where most Air Force personnel didn’t in trying to get some answers regarding Kelsey’s death.

“I’m fumbling around in the dark, trying to get a copy of the report [on Kelsey’s death] for the Andersons,” Fritz says. “Thus far, we’ve not been very successful.”

Chris says that he learned, through Fritz, that the investigative file on Kelsey’s death has been completed and is sitting somewhere in the OSI headquarters in Quantico, Va.

“We know that the case file was finally closed on May 22, 2012. Bernie learned that there are supposedly 282 files and Kelsey’s file is No. 82,” Chris says. “What does that mean? No. 82? Does that mean another year until we get it? Another five years?”

Fritz says that Kelsey’s file was indeed a part of “a specific number of files” in Quantico.

“They handle the sequence [of the files] in the order they received them,” he says. “I’m not part of the decision-making process. I’m attempting to be a conduit for information. You’ll have to excuse me if I can’t get into hard specifics. The Andersons are good folks. They suffered a horrible tragedy. There’s nothing anybody can do to make it right, but if they had that report, at least they could know what happened. If there was some methodology to kick that loose and hand them the report, I would have done that a long time ago.”

The man who ultimately may kick things loose is attorney Matt Crotty.

“Plus, Matt’s a military man,” Sue says.

Following five years in active duty, serving in different U.S. Army assignments after 9/11, Crotty is currently a lieutenant colonel in the Washington Army National Guard.

“I’ve been in war zones and, unfortunately, I’ve been in units where people have died. But in my experience, the military is usually forthcoming,” Crotty says. “That’s why this sounded so odd.”

The Andersons filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Air Force in August 2012, asking for a copy of their daughter’s records, including the autopsy. But similar to their other requests for help, they received no response. That’s when they retained Crotty.

“When the Air Force didn’t respond, we could go ahead and sue them flat-out or we could appeal one more time, which I thought would be the right thing to do,” Crotty says. “We filed an appeal on May 16. The government is supposed to respond to that within 20 business days. So we gave them that much time, and then some. But still, no response. No phone call, no email, nothing.”

Crotty’s next legal maneuver was the biggest shoe to drop in the case of Kelsey Anderson. Crotty filed a lawsuit June 17, accusing the United States government — and in particular, the U.S. Air Force — with “repeated failures to comply with the Freedom of Information Act.” The government had 30 days to respond in a court motion.

“How tough a court battle lies ahead? It depends how nasty the Air Force wants to be,” Crotty says. “We think it is pretty cut and dry. They didn’t do what they were supposed to do in the time they were supposed to do it.”

And if the Air Force argues that its administrative backlog is a valid excuse for failing to produce Kelsey’s records, Crotty will be quick to point out that a federal court in Illinois ruled in 2002 that a backlog is not acceptable in providing a report that has already been completed.

Permanent Change of Station

The Andersons say that they felt they had little recourse other than to sue the federal government to get the truth. Quite simply, the trail of information went cold, particularly around Guam.

“A lot of people from Guam sent condolences to our family, but they said they were told not to talk to us,” Sue says. “And they told Chris that if he tried to go over there, they wouldn’t let him on the base.”

As I tried to track down the key players who would presumably know what happened to Kelsey Anderson, I was repeatedly told that they had been reassigned.

“Sir, he’s PCS,” Guam OSI Agent P.J. Davis says when asked about Agent Jason Larsen, the lead OSI investigator into the incident. “PCS means permanent change of station.”

Officials in Quantico aren’t talking either, other than to say that the Andersons could contact them directly with their questions or concerns — which is what they’ve tried to do for the better part of two years.

“You really shouldn’t have to sue them to do this, but that’s what it’s come to,” Chris says. “Why would the government want to keep something away from a family? We have to have closure on this. And what we just don’t understand is that they put themselves above the law.”

Sue said she wasn’t “100 percent sure that Kelsey committed suicide on June 9, 2011. But if they can show me something that convinces me, I’ll accept that. I think somebody killed her or she killed herself over something horrible. And besides, we can’t be the only people in America who are going through something like this. They just can’t keep doing this. Maybe we can stop it.”

EPILOGUE: The Phone Rings

Last week, the Andersons got the first sliver of hope that answers might soon come. Following media coverage of the case, the couple finally received a phone call from top Air Force brass.

“Guess who I just got off the line with? Gen. Mark Welsh, the chief of staff of the Air Force,” Chris says, adding that recent news coverage was “definitely ruffling some feathers.”

“[Welsh] told me he wasn’t in a position just now to tell me anything, and that he just recently found out about Kelsey’s case,” Chris says. “I asked [Welsh] if he had a daughter, and he told me he did. He said, ‘I don’t know what I would do if I were you.’”

Chris says Welsh gave him “a long line of excuses” but ultimately shared his personal cellphone number, telling him that he should expect answers regarding his daughter’s death “sooner than later.”

A version of this article first appeared in Boise Weekly.