In 1993, the same year that launched the bloody, demon-blasting computer game Doom, a tiny developer called Cyan from a mid-sized city called Spokane released a computer game called Myst.

For nearly a decade, it held the title of best-selling computer game of all time.

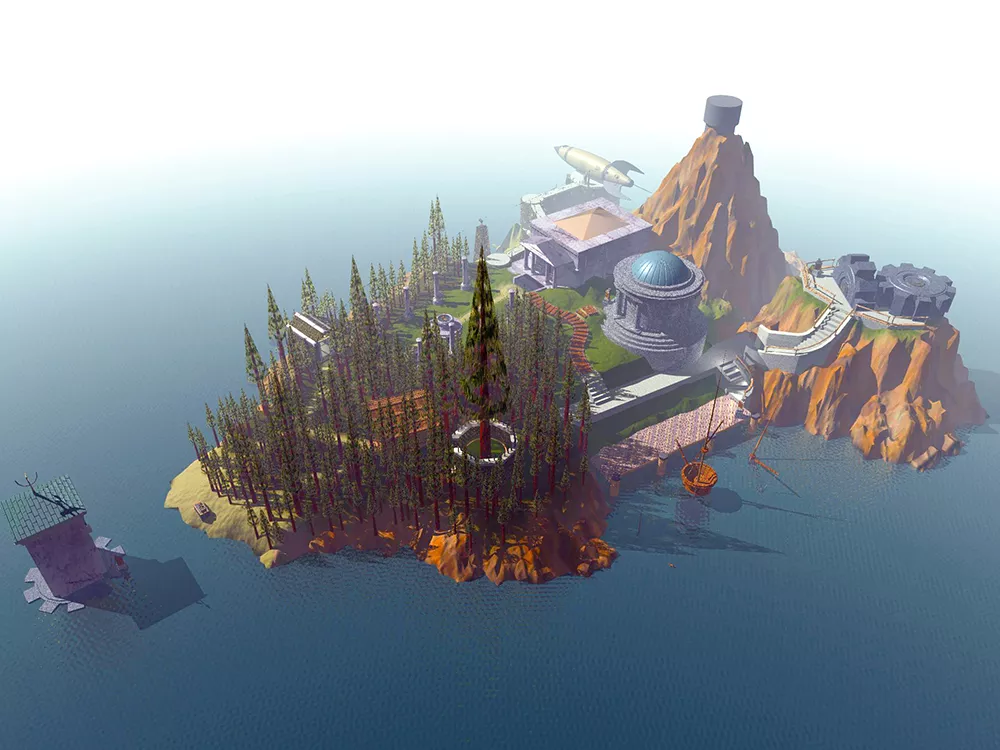

It did so without machine guns or combo-punches. It started quiet. Under a cloud of stars, a glowing book beckoned from blackness while the wind whistled. Open the book, place your hand on the picture on the first page, and get sucked into a multiverse of weird worlds, with fog-drenched forest boardwalks and red-stained torture rooms, a music-powered spaceship and a sound-navigated subway car, obscure puzzles and hidden passages all rendered in gorgeous 3-D.

In a double-wide mobile home on a hill in Chattaroy, Wash., three brothers created worlds. Rand Miller was the lead programmer. Robyn Miller designed the art. Even their kid brother Ryan, a senior in high school, chipped in, writing reams of backstory that became tomes in Myst’s in-game library.

In the Myst mythology, creative types with the right grasp of language, with the gift for an eloquent phrase, can summon entire “Ages” — beautiful, strange and dark worlds — into reach. Not a bad analogy for the Miller brothers.

But they wrote a catch into the backstory. If the authors aren’t careful, the ages become unstable, the ground quakes, and the whole world collapses into nothingness.

In a way, that’s what almost happened to Cyan.

Surreal Adventure

Rand Miller calls from New Mexico — appropriately, he celebrated Myst’s 20th anniversary at Carlsbad Caverns.

The Millers knew they had put together a decent game. But they didn’t expect it to sell more than 10 million copies, to drive the adoption of the CD-ROM, or to land in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection of significant videogames. They didn’t expect it to be a game that would, two decades later, inspire a lengthy retrospective over its legacy like last week’s Grantland piece.

“It was our little surreal adventure,” Rand says, echoing the game’s tagline. With profits soaring, they constructed headquarters that looked like something out of Myst. A jagged brick edifice that appeared torn out of the building’s face arched over the entrance, while waterfalls poured down rocks out back. Inside, artists worked beside a small library, under the stars of an artificial planetarium.

Cyan had enough money for a nearly a limitless canvas for the sequel, Riven.

“A painting is finished if you run out of money and run out of time,” Rand says. “[But] Riven, in a lot of ways, had kind of this unlimited budget. It was being funded by Myst.” The freedom was exhilarating; the pressure, exhausting.

Riven was released four years later to critical praise. It was hyped in an epic-length Wired story, marveling over how a success like Myst could come from a isolated place like Spokane. Riven was longer. It was a lot harder. And it was the company’s last clear success.

As Robyn, the artist, left the company to create more linear stories, Rand’s ambitions turned to “building something that would never end.” He was intrigued by massive multiplayer games like EverQuest, where thousands of players could play simultaneously. But instead of EverQuest’s addictive grind of killing monsters to get bigger weapons to kill bigger monsters, he wanted a different draw.

“What we were looking to do is to play on a different emotion: The human desire to explore. The reason you went to Carlsbad Caverns was to explore, to see what’s in the next cavern,” Rand says. “What I was looking for was drama and storytelling, like Lost instead of Family Feud.”

While another studio created direct Myst sequels, it spent the next six years designing a multiplayer Riven follow-up, Uru. It set up an assembly-line workflow to constantly churn out new content. It constructed a sprawling complex across the parking lot from its headquarters to house a sizeable staff. They mapped out elaborate stories, created characters, planned in-game events. “The world would just get bigger and bigger, and you could explore with other people,” Rand says.

It was a huge risk. A few massive multiplayer games have been towering successes; others have bankrupted entire studios. But Cyan never got the chance. In 2004, just as the game was about to be released, Uru’s publisher Ubisoft shuttered its entire online division. It was a huge blow to nearly six years of development. Most of Uru’s content trickled out in the form of single-player games and expansion packs, but Uru was never truly released in its intended form.

“I think that you have to look at things that fall apart as things you can learn from,” Rand says. “You have to make sure that failures are just stumbles, and not complete collapses.” For a time, Cyan teetered on that edge.

A year later, the company released one last game, Myst: End of Ages, then prepared to stop all active software development. “I remember going into the conference room and saying that’s the end,” Rand says. “We don’t have anything in the pipeline. We’ll have to let everybody go.”

A New Age

Stars still shine down from the planetarium at Cyan, but on an empty hardwood floor. The artist hubs and the library are gone.

Yet Cyan has survived. Soon after Rand announced mass layoffs, a Myst fan working for Turner Broadcasting System began putting together a deal to temporarily resurrect Uru online as part of its GameTap subscription service. It allowed Cyan to reverse its layoffs just as the first iPhone was released.

“I think the mobile platform came at just the right time,” Rand says. The company released a few original casual mobile games and the Myst games for mobile devices.

In Cyan’s headquarters on a Thursday afternoon, the halls are mostly quiet. A few of Cyan’s remaining employees work on updating the Myst for modern PCs. To keep Cyan alive, the company ran a separate game-testing division, performed third-party work and rented out office space to separate companies. Some, like Ryan, felt their passion had been extinguished when Uru’s online component was canceled.

“Morale plummeted. We had people walking around like zombies,” he says. “There was a whole air of ‘Anything we do for a while is going to be surviving.’ We were the patient with the IV drip, and there were times you said, ‘You know what, you need to pull the plug.’ This is not the life you want to live.”

Ryan left Cyan and became a pastor. On Sundays, he preaches in the building once intended for Uru’s development, now converted into a church. But for the first time in years, he says he sees a pulse at Cyan, as the company prepares to launch an ambitious project through Kickstarter.

The world of gaming sits in a strange position. Publishers outlay multimillion-dollar budgets hoping to get billion-dollar returns. It took Myst more than three years to sell 3.5 million copies. The most recent Tomb Raider reboot sold that amount in just one month — and its publisher considered it a disappointment.

But at the same time, thanks to digital distribution methods, publishers are less relevant than ever.

“From a business perspective, not having a publisher is pretty sweet,” Cyan’s president Tony Fryman says. In a way, the fans have become the publisher. Tim Schafer, who designed humorous adventure games during the Myst era, asked fans for $400,000 through Kickstarter last February to make another vintage point-and-click adventure. They gave him $3.3 million.

And few fans are as passionate as Myst die-hards. They continue to fly into Spokane from around the globe for semiannual “Mysterium” conventions. They obsess over the series’ fictional language, one couple inscribing a “D’ni” phrase on their wedding rings. Last year, an Australian fan spent $10,000 creating a real-life replica of the Myst Book that allowed the entire game to be played in the book’s small window.

Rand says Cyan plans to launch its own Kickstarter project, a sci-fi successor to Myst, as soon as next month.

At this point Rand won’t reveal the title, but he offers this image as a teaser: A white picket fence and an old farmhouse on a strange and alien world, without explanation for how they arrived.

“In this particular game that we’ve designed, you end up being placed on another world that” — Rand laughs cryptically — “that’s very intriguing.”