Wednesday, September 11, 2013

MAC director Forrest Rodgers' rocky years as president of the High Desert Museum

When the Museum of Arts and Culture hired Forrest Rodgers as its new executive director in 2011, the accompanying press release gushed about his previous experience as president of the High Desert Museum in Bend, Ore., from 2001 to 2007: “He implemented a strategic marketing plan to build the museum’s brand awareness and reversed a 40-percent decline in paid attendance by creating a new focus on wildlife and living history. He also implemented an eight-year, post-campaign budget to stabilize operations and secured donations to reduce the museum’s post-construction debt from $3.3 million to $1.5 million.”

Local journalists, including myself, followed that lead, focusing on Rodgers’ amazing record at reversing a decline in attendance in our articles when he arrived. In his response to a recent investigation into staff reaction to his leadership, Rodgers referenced the “turnaround” he brought to the museum.

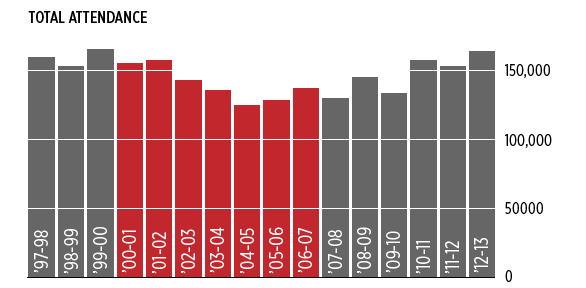

But now that complaints about Rodgers’ leadership have surfaced at the MAC, it’s worth rexamining his record. We all missed the full story: The High Desert Museum under Rodgers’ leadership was defined by staff cuts and the lowest attendance in at least 20 years of museum history. Only in his final year did he see a brief spike in attendance — and that didn’t appear to have lasted.

Before we dive into the numbers, let’s get some context straight: The MAC and the High Desert are very different museums: High Desert actually partly serves as a zoo with live animals, something Spokane hasn’t had since Spokane stopped walking in the wild in 1995. The MAC has massive collections that have to be warehoused and maintained, even if it never opened to the public. The MAC relies on state money to survive. The High Desert does not. Bend is a tourist-driven town — about two-thirds of the visitors to the High Desert are out-of-towners — Spokane is not. And Bend flew much, much higher in the housing market boom and crashed much, much harder in the recession compared with economically dull Spokane.

Rodgers arrived at the museum as Vice President for Development and Public

Affairs in February of 2000, took over as interim director that September when the president left, and then was finally appointed

president in July of 2001. The museum had a big debt from its uncompleted

expansion, and money that had been raised for that expansion were being spent on

operating the museum.

His goal was to complete the fundraising to finish the expansion, reduce the overall debt, and increase admissions.

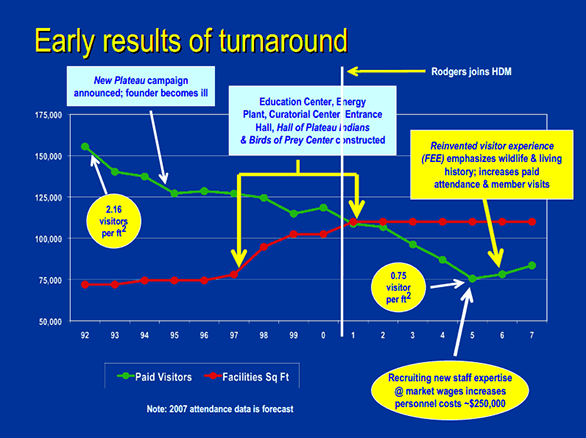

But between fiscal year 2002 and fiscal year 2005 overall attendance at the museum plunged nearly 20 percent, despite the completion of the major expansion intended to attract tourists. Even as Bend’s overall tourism was increasing, even as it marched toward becoming one of the smash successes of the housing boom before becoming one of the worst cases of the recession, attendance at the High Desert kept falling.

Taking Attendance

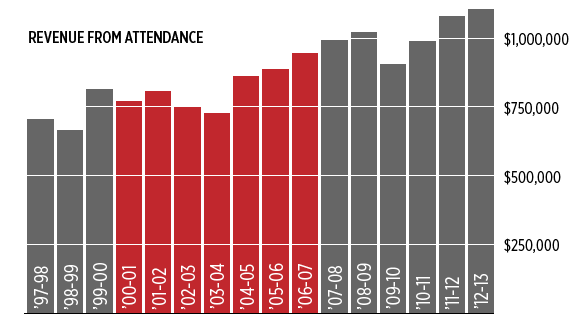

That “turnaround” was temporary, at at least in terms of overall attendance. Attendance increased minimally one year, spiked the next, and then fell again at the later half of 2007 with the Bend’s housing market. Only recently has it consistently increased.

Three sources of data illustrate this, none of them perfect.

The first tracks pure attendance from fiscal year 1998 to 2013 (at the High Desert and the MAC fiscal years start in July instead of January. FY2013 is already finished.) It doesn’t show how many were paid visitors — some of the visitors got in for free events or because they were very young — but it’s the purest way of understanding how many people showed up at the museum.

The second is a chart of “paid attendance” that Rodgers sent over. (Rodgers was extremely helpful in providing the Inlander data and documents.) While it cuts off before Rodgers left, and only projects the FY2007 figures, it shows that attendance had its declines before Rodgers arrived, but also that the museum faced some of its worst years under his leadership.

The last graph tracks the amount of revenue raised through museum visits. Because of inflation and an increase in ticket prices, the dip appears to be smaller. But it’s still a useful way to judge how much money attendance was bringing in.

Why did attendance decline so much during his tenure?

“Well, ask the visitor,” Rodgers says. “I’m trying to remember way back to the those days. Like this institution, we were trying to attract resources with limited resources. We had staff that were not focused on the visitor experience. And we had to go through some major transformations for people to understand that the funding model did not support the business model.” The expansion added huge operating costs and appeared to have drawn few visitors.

Asked if it will take over five years to see an increase in attendance at the MAC, Rodgers says: “We can’t afford that.”

Big Debt, Big Cuts

Like the MAC, there were big cuts at the High Desert. When the Sept. 11 attacks hit, it dealt a big blow to the tourism economy. The first big cuts to the museum hit that December, when 7.5 positions were eliminated from the payroll. “Our earliest round of layoffs was to get our staffing in line with what we could support,” Rodgers says. “And then hiring people who were focused on turning around the visitor experience.”

By October of 2004, the museum had suffered two additional budget cuts. “What we’re really doing here is making some program reductions and staff reductions that in the near term will shrink us, but will allow us to grow in the future,” he told the Bend Bugle at the time. With the elimination of a third of the staff, the museum planned to rely more on volunteers going forward.

“We have a high fixed-cost structure,” he said to the Bugle. “Permanent exhibits cost a lot of money. It’s hard to always continually change them. A major part of what we’re going to focus on is interpretation, volunteers, living history.”

But in Spring of 2006 — over five years after Rodgers took the helm — things still looked dismal: “Top managers quit museum,” headlined the Bend Bulletin in April 2006. “Low attendance hurts finances at The High Desert Museum.”

Three major staff members, the Vice President of Finance, the Director of Development, and the Director of Development, suddenly left at the span of a few weeks, citing personal reasons. Back then, the museum denied that it had anything to do with the museum’s financial struggle. But today Rodgers says the financial challenge played a part for at least two of them. “There was on the part of our CFO, the continued burden of not having enough resources, for us not having enough money, to do what we needed to do,” Rodgers says. “We had to earn or raise 2.5 to 3 million dollars every year.”

The Bend Bulletin reported that expansion turned out to be one of the museum’s biggest liabilities during the Rodgers tenure:

The museum, located on 135 acres south of Bend, posted operating deficits of $1.02 million, $116,439 and $184,923 in fiscal years 2002, 2003 and 2004, respectively, according to Internal Revenue Service tax forms filed by the museum. Numbers for 2005 are not yet available.

Low attendance is the No. 1 problem, which is compounded by the museum’s 158-mile distance from Portland, museum officials say.

…

The museum still has a debt of $1.9 million remaining from the $25 million New Plateau campaign that doubled the size of the museum’s facilities in 2002, Carroll said. The museum expects trustees to pledge $415,000 to help pay down the tab, she said.

The campaign operated under the mistaken premise that “if you build it, they will come,” she said.

The project essentially overbuilt the museum to accommodate 175,000 to 200,000 paid visitors annually, Carroll said. The museum has run short by more than 100,000 paid visitors each year since.

…

The museum taps private donations, capital reserves and nonoperating revenue sources like federal grants to balance its budget each year, said Tim McGinnis, chairman of the museum’s board of trustees.

“We have funds that we set aside in the past to help the museum through difficult periods,” McGinnis said. “(Some trustees) provided money out of their own pockets to put in the reserve fund to help balance the budget.

Reducing the debt came at a price, with less money raised for the endowment, cuts to staff and programming, and trustees pressured to donate their own funds. And ultimately, it wasn’t enough. “If there was an area where I failed it was to not eliminate, in my relative short amount of time, a very significant campaign debt,” Rodgers says. “Fundraising against debt is one of the most difficult tasks you have.”

His final year at the museum was a bright spot after five challenging years. That year, attendance spiked up. But feeling the strain on his family life, he left the museum in 2007. He says he also had a disagreement with the board over using the endowment to help pay off the debt. “I knew the board needed to have a director to whom they would listen,” Rodgers says.

When he left, the Bend Bulletin story read, “Rodgers pointed to a recent rise in paid attendance after 12 years of declines, the hiring of more staff and a focus on more varied visitor programming as some of the major achievements during his tenure.”

The next year, as the economy began collapsing, attendance fell again.

After Rodgers

When Rodgers left, the board intentionally hired Janeanne Upp as their next president for her financial expertise, says John Furgurson, who handles public relations for the High Desert Museum.

“The board at the time saw a need for very diligent financial controls, and that was a major reason why they hired her,” says Furgurson. “And her job was to shore up the finances and get the museum on a good financial footing. She’s accomplished that in the six years.”

Rodgers brought debt down from $3.3 million to $1.5 million over six years, but Upp finally finished retired the debt completely this year. And despite the challenges of the Great Recession, overall attendance has climbed considerably for the past three years, finally making up the ground lost during the decline during Rodgers’ tenure. (Overall, Bend’s tourism bounced back from the recession more strongly than many similar cities.)

Just this year, the museum finally surpassed its attendance of fiscal year 2001. If Yelp is any indication, visitors love it. It’s possible, of course, that some of the recent success came from the foundation that Rodgers laid. Some visitors praise the “living history” aspect — where staffers or volunteers greeted them in period costume.

Still, Furgurson notes two big changes that have made the museum successful lately. The first is something that Rodgers intends to bring to the MAC in Spokane: Broad educational programs perfect for field trips. But the second successful strategy they used was to go in exactly the opposite of the direction the MAC is heading in. At the MAC, Rodgers says he plans on switching out exhibits less often. The High Desert went in the opposite direction.

“One of the reasons that I believe that our numbers are good in terms of attendance, we have a lot more exhibits that change more frequently,” Furgurson says. “During Forrest’s tenure we typically would only change out one to two exhibits per year. Now we have nine to 11 exhibits change a year. This last fiscal year, we had 11 different new things to come and see. That’s 11 different reasons for people to revisit … Our market research showed there was a consensus of people who said, ‘I haven’t been there in three or four or five years, because there’s nothing new there.’ It was determined that we need to do a better job of getting more exhibits.”

A case can be made that Forrest Rodgers brought a “turnaround” to the High Desert museum while he was president. But a much stronger case can be made for a turnaround for his successor. Over the same amount of time in a much tougher financial climate, she managed to address the museum’s financial woes and drive attendance considerably higher.