Night after night, as America has erupted — with peaceful protests and destructive riots — journalists have been there in the middle of it all, documenting events, trying to put them into context and acting as independent witnesses.

It’s not a formula for making friends. Reporters have been bruised, blinded, tear-gassed and arrested by police, even after they identified themselves as working members of the press. They’ve also been stomped and pummeled by some extreme protesters whose ideologies (left or right) would have them wrongly believe that reporters are enemies of the people.

Part of the problem can be traced to a fundamental misunderstanding of what journalism is.

Journalism doesn’t exist to make you comfortable, to reaffirm your every belief, to turn your friends into heroes and your enemies into villains. Politicians, police chiefs and protesters would do well to take note: Journalism that works for your side and your side alone isn’t journalism at all. It’s advocacy, and while advocacy can be vital to our civil discourse, when it’s dressed up as news, it’s fake.

Journalism’s real job is to seek the best obtainable truth — not your version of truth, but the best version that we can uncover and support with facts — and then share what we know and how we know it.

The coronavirus pandemic has made this point especially clear: For the public’s own well-being, reporters have sought to provide the best obtainable information, citing experts, research and relevant case studies from other places. To do anything less, say, to advocate for a certain unproven treatment, could literally cost people their lives.

It’s easy to see how people could get confused. They spot an article they love, they share it on social media, their friends like it, it somehow affirms a value they identify with and they begin to find some common cause with the news outlet that did the reporting. Which is fine, perhaps — until journalists at that same news outlet present a story and facts that don’t cohere with those fans’ worldview.

"What would you say about a neo-Nazi who doesn't want to be identified or a skinhead or an abusive police officer?”

Then suddenly they’re threatening to “cancel” the offending news outlet and its journalists. Which isn’t really helping anyone. Yes, we should all hold reporters to account for their mistakes, but we should also make sure we’re not mistaking journalism for something else.

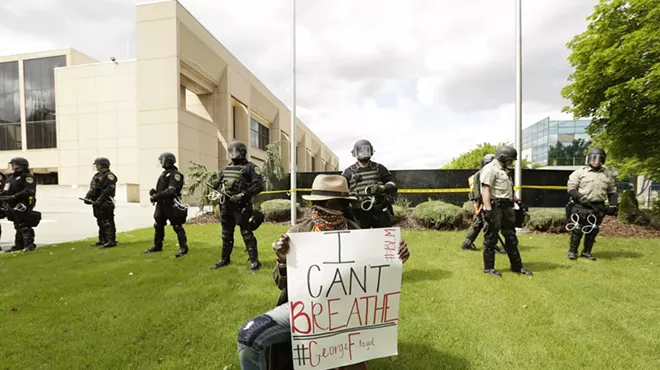

Lately, news photographers have had to defend the images they’ve captured during public demonstrations from some protesters who argue that demonstrators’ faces should be blurred and identifying features obscured. They say they’re worried about being targeted or doxed by right-wing extremists.

It has put those photographers in the uncomfortable position of saying no to people whose calls for justice may indeed be righteous. For while journalism ethics say that reporters should weigh potential harm of their coverage, they also should not distort facts or context. With journalism under constant attack by those who dismiss it as “fake news,” manipulating photos would undoubtedly do grave harm to people’s confidence in the independent press.

“The whole point of a demonstration is to be seen and heard because you're not being seen and heard in other more conventional ways. So if we weren't there documenting who is saying what, then we would be criticized,” says Al Tompkins, a senior faculty member at the Poynter Institute for Media Studies. Tompkins helped to write the codes of ethics for the National Press Photographers Association and the Radio and Television Digital News Association.

“One of the other issues that we would have is this: Are you saying that you only don't want to be seen while you're demonstrating? But while you're doing a charitable act, while you're doing good things, while you're protecting the Walgreens from getting broken into, then it's good to show?” he continues. “And what would you say about a neo-Nazi who doesn't want to be identified or a skinhead or an abusive police officer?”

There’s also the fact that for many demonstrators, it is a point of pride to show their faces at these protests and they have readily given their full names to photojournalists so that they could be identified. To erase them from images taken at these historic demonstrations would certainly do them harm as well. Besides, it's worth noting that thousands of other images are taken at protests — by demonstrators themselves, police body cameras, surveillance cameras and more.

None of this is to distort or exaggerate the facts. Protesters, on the whole, have welcomed news coverage. And in the end, the vast majority of attacks on journalists at recent demonstrations have come not from protesters, but the police. The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, a project of the Committee to Protect Journalists and the Freedom of the Press Foundation, has found that law enforcement was responsible for some 80 percent of violent assaults on journalists in recent days. In some cases, the press might have been inadvertently injured in the chaos of the protests they were covering.

More troubling, though, is the fact that many of the reporters were specifically targeted by police. Thankfully, we know this because independent journalists were there to witness it, photograph it, put it on video and share it for the world to see. ♦