Artist Ric Gendron has plenty to look forward to this Father's Day: three grown children, numerous grandchildren and two great grandchildren, plus seven siblings, and countless extended family members. That he's around to celebrate at all is a big deal, but not one Gendron wants to dwell on.

Home for only a few weeks since the juggernaut of Western medicine snatched him back from rapid decline, tethered him to dialysis, and predicted a dire albeit short future, Gendron is instead focused on the present and forging his own way forward.

He's pursuing "traditional medicines, a traditional [way] through ceremony," says Gendron, a member of the Sinixt Band of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, and the Umatilla Tribe of Oregon.

And although details about his health issues have been widely reported, including in a new book produced by Marmot Art Space, Gendron would rather not give name — or power — to his ailments.

After hearing the oncologist's dire prognosis, for example, Gendron told his kids, "That doctor's full of shit."

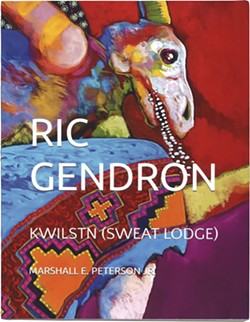

The new book's title, Ric Gendron: Kwilstn (Sweat Lodge), was a natural choice, he says.

Kwilstn is pronounced close to "quilt-skin," and comes from the word kwilstnm in the Okanagan Colville language (nslxcin), meaning to take a sweat bath.

"I attend sweat lodges every week and I've been doing it for over a half a century," says the 68-year-old Gendron. "So my whole life is kind of based on beliefs and traditions of the sweat lodge and that just sort of trickles into my paintings."

Kwilstn features 51 of Gendron's paintings and a smattering of background information about the artist's nearly four-decade career.

The new book is the impetus for our interview that takes place in the living room of Gendron's home, located upriver from the dam at Grand Coulee, where he was born in 1954.

"They tore that hospital down," says Gendron, setting up the punch line. "I think after I was born, they couldn't do any better."

However, like the Columbia River outside Gendron's door, the conversation meanders.

Gendron remembers being eight years old at the home he shared with his parents and nine siblings and being struck by the view of the dam.

"I used to steal my oldest sister's typing paper and use it as drawing paper," Gendron recalls. "And I remember sitting down and drawing the entire skyline with all the power lines and sagebrush."

When Gendron's family relocated to Spokane and he began attending North Central High School, he could finally envision a future in art. Influenced by Creepy comic books and Gilbert Shelton's The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers illustrations, Gendron and his school chums created an underground comic they called "Hot Rats" after Frank Zappa's 1969 album of the same name.

Gendron knew he wanted to be an artist, like Ed "Big Daddy" Roth, whose Rat Fink illustrations are synonymous with California's '50s and '60s hot rod craze.

"I was just blown away by the '60s art," he says, including posters for the Fillmore music club and Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco.

"But then, you know how a lot of kids' dreams get crushed?" Gendron asks.

Even now, people still ask him what he does for a "real job," he says.

So if any of his grandkids or other family members said they wanted to do art, Gendron would respond: "Go for it."

That's what Gendron did in 1983. A well-paying but dead-end job at Hewlett-Packard drove Gendron back to Spokane Falls Community College to pursue art.

"I always heard people saying, 'God, I can't wait till I retire so that I can do what I really want to do,' like artwork or whatever," Gendron recalls. "And I thought, 'Why wait?' Most people wait until they retire, then they live a few years and die, so I didn't want to do that."

Initially, Gendron attended SFCC for graphic design, but the emphasis on computers and some of the classes weren't a good fit, he says. He switched into fine arts, thrived under instructors Jo Fyfe, Jeanette Kirishian and Dick Ibach and tried a variety of art media.

"I'm too lazy to sculpt because I don't wanna haul heavy stuff around," says Gendron, laughing. He also hates drawing, but likes printmaking, and was working with good friend and fellow artist Joe Feddersen "until the world stopped" during the pandemic.

And painting?

"I loved it," says Gendron, especially acrylics. "I loved the vibrancy. I loved the quickness of it" compared to oil painting.

After SFCC, Gendron relocated to Seattle to earn a bachelor's of arts from Cornish College of the Arts, but a difficult divorce sent him back to Spokane. He contemplated becoming an art teacher, but instead worked side jobs to support himself and his three kids while committing himself to painting.

Gendron has achieved considerable regional acclaim, with prestigious stints including an artist residency at the Institute of American Indian Arts and a solo traveling exhibition and accompanying book, Rattlebone. But there is another side to the so-called Western art genre he wants no part of.

"How many paintings, how many bronze sculptures, how many anything can you do of an elk, you know?" he asks rhetorically. "Or a cowboy on horseback or a Native family standing all stoic and beautiful, you know?"

It isn't just the — to his mind — overpriced market for Western art that galls him, but also how the imagery plays into a larger narrative of ignorance about Native Americans.

"What bothers me is this is how we're portrayed as people," Gendron says. "I've still been asked questions — not long ago — 'Do people still live in tipis?' or I've heard 'You don't have to pay for anything because the government pays for everything, the government gives you money every month.' It's just crazy."

In contrast, Gendron offers an authentic, often gritty version of what it's like to be Indian in America. He's also a role model for making it as an artist, neither because of nor in spite of being Native American, but just because he has never given up on his dream.

"I'm glad that I'm able to do that," he says. "And I'm glad that I don't have to work so hard at it," he laughs.

"There was a time when I wanted to shake up the world, you know, and be as militant as I can," he says.

Now, however, Gendron has mellowed. As we're talking, the sun beats down, a car passes by outside, and the Columbia River rolls on.

"I mean, you should already know that racism sucks, that there's so many things, so much out in the world that's wrong," Gendron says.

He still wants his kids and grandkids to do what's right, he says, but no longer feels it's his duty to try to teach people what they should already know.

"My job is to go into that little studio and create paintings," Gendron says. "My job is to take care of my family. My job is to try to love people the best I can." ♦

Visit marmotartspace.com for more information about Ric Gendron: Kwilstn (Sweat Lodge).