Washington, ostensibly, is a liberal state. It hasn't voted for a Republican governor since 1980 and hasn't voted for a Republican president since 1984. Yet it has a tax system that would give Bernie Sanders nightmares. It punishes the poor and lets the rich off easy.

That's why David Schumacher, director of the state Office of Financial Management, has such trouble trying to convince voters that Washington's tax burden as a share of its economy is relatively low. For many residents, it certainly doesn't feel like a low-tax state.

That's because for the bottom 40 percent of earners, it isn't.

"Convincing them they live in a low-tax state is a fool's mission," Schumacher says.

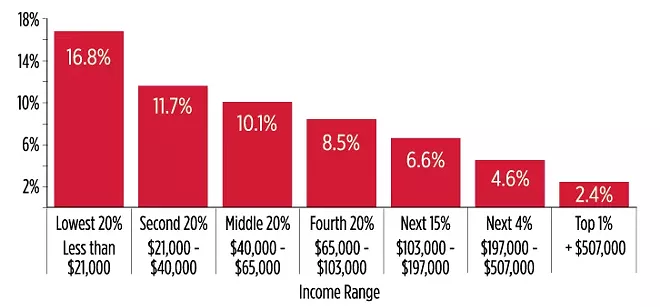

In its 2015 "Terrible Ten" rankings, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy described Washington as having the absolute worst regressive taxes in the nation — and it wasn't even close. Our sales-tax-heavy state tax system means that the bottom 20 percent of our non-elderly citizens pay nearly 17 percent of their income in taxes. The top 1 percent? Only 2.4 percent.

The big culprit is Washington's sales tax, which — while it exempts groceries — punishes those living paycheck to paycheck. Not only that, but the state's Business and Occupation tax charges based on gross receipts, meaning small businesses that are losing money still might face a big tax bill at the end of the year.

Combine that with subpar K-12 education funding, which has resulted in districts relying increasingly on local levies to make up the difference. For districts with expensive homes in cities like Seattle, it's a lot easier to raise large amounts of money through local property taxes than in small rural towns like Deer Park. And while the state chips in part of the difference, it's not enough to make up the wide disparity between rich districts and poor districts.

"It's a double whammy," says state Sen. Andy Billig (D-Spokane). "The millionaire in Bellevue pays 2 percent of their income in state and local taxes and gets the best schools for the community. The low-income person in Wapato is paying 17 percent of their income in state and local taxes and getting worse-funded schools."

That inequality is central to the state Supreme Court ruling that the state legislature was violating the constitution by failing to adequately fund public schools.

And as Democrats in the House and Republicans in the Senate hammer out their respective budgets, both are trying to raise money for education while repairing a tax system that hurts the poor far more than the rich.

EVERYTHING BUT AN INCOME TAX

The most obvious way to move the tax burden from the backs of the poor to the pockets of the rich is also the most politically impossible.

Puget Sound economic forecaster Dick Conway, author of the study "Washington State and Local Tax System: Dysfunction & Reform," says that Washington has the worst tax system in the nation, but most proposals are dodging the real issue.

"We are one of the few states that doesn't have an income tax," Conway says.

He says that most of the other states without an income tax have enough oil, gas or gaming tax revenue to compensate. Washington doesn't.

His proposal is incredibly simple: Everybody pays a 10.5 percent income tax, and all other state taxes are eliminated. Even a flat income tax would come as a major relief to low-income earners who lose a huge chunk of their income to sales taxes.

But every time an income tax has been attempted recently in Washington, it's been absolutely slaughtered at the polls. The most recent attempt was Initiative 1098 in 2010, proposing an income tax on high earners: Nearly two out of every three voters voted against it.

"People are suspicious that if you impose an income tax, the government wants to pick your pocket," Conway says.

This year, Democratic press releases eagerly point to how "a janitorial staffer could pay up to 686 percent more in taxes as a share of his income as the CEO whose office he cleans," yet an income tax increase isn't on the table. Instead, part of the House Democrats' plan to raise more than $1.5 billion a year would actually increase sales taxes: The Democrats' plan would slash a number of minor exemptions, like those on bottled water and extracted fuel. It would also level sales taxes on out-of-state internet purchases, intending to help local businesses compete with online retailers.

But Washington state Rep. Kris Lytton, chair of the state finance committee in the Democratically controlled House, says that other pieces of the plan would reduce the overall tax burden for the poor.

"Half the people in our state will pay less in taxes," she says.

The plan reworks old taxes to hit the rich harder. It would eliminate nearly three-quarters of businesses from the B&O tax, then slam some of the biggest businesses with a 20 percent rate hike. Similarly, the tax on real estate sales would be rejiggered to tax large transactions at a higher rate than small ones.

It also introduces one big, new tax proposal aimed at the super rich: A capital gains tax.

Democrats euphemistically refer to it as "ending the corporate tax break on capital gains." Aimed at big windfalls of investment income — and excluding sales of single-family homes and farmland — it's intended to raise more than $350 million a year from less than 2 percent of the population.

The problem with a capital gains tax, Conway says, is its lack of stability. The amount of revenue from a capital gains tax can swing wildly from year to year. Schumacher says that's easy to fix — you just need to set aside a chunk in a reserve account to smooth out the peaks and valleys.

Still, conservative groups object to the notion of a new tax, wherever it comes from. It may start limited, they say, but it won't necessarily stay that way.

"Capital gains is a new tax structure which will grow in the future," predicts the Washington Policy Center's Paul Guppy.

And Republicans? They see it as just an income tax by another name. And Washington, remember, hates income taxes.

REDISTRIBUTION OF PROPERTY TAX

So instead of raising revenue with an assortment of taxes, Senate Republicans are proposing one big move, intended to shift the burden of funding K-12 education from the districts to the states and from poor areas to wealthy areas.

"I think we have to take bold, decisive action this year to do things differently," says Sen. Hans Zeiger (R-Puyallup). "We want to make a clean break from our current system;"

In other words, if the problem with disparity in education is with varying levy rates, then eliminate the local levies for a year. But also, level a flat $1.55 property tax statewide for every $1,000 of assessed property value.

That means that in particular, King County would see tax bills skyrocket, while Eastern Washington would see relief. Schumacher, of the state's Office of Financial Management, estimates that about 40 percent of the state would see their tax bill increase, while 60 percent would see it decrease.

In the subsequent year, the plan would restore the ability of local districts to pass levies — but at a lower rate, and only for expenses that aren't considered "basic education."

Democrats note that the Republican plan raises less money for education than theirs does. They also note that, depending on how many districts raise levies after the initial moratorium, property taxes could increase in more places than advertised.

They've borrowed from the anti-tax-rhetoric playbook. Billig and others argue that a flat property tax rate is unfair, because those who own expensive property would pay more than those who own cheaper properties. That's an issue with property taxes in general.

After all, with the way that property values have skyrocketed on the state's west side, it's hard enough to afford a home without needing to pay a higher property tax on top of it.

With a property tax increase, elderly people on fixed incomes may struggle to pay their tax bills.

"I don't think we need to tell that working-class family in Seattle that the only way you can live in your state is to sell your house," Billig says.

But ultimately, Billig says, neither side's arguments have won out. Budget negotiations are locked in a stalemate.

"The House and the Senate plans are both dead," Billig says. "Neither one of them can pass the full legislature."

Whatever tax plan the House and Senate eventually agree upon will likely be the product of a compromise — and a significant disparity between the rich and the poor will remain. ♦