Up a dirt road behind Eastern Washington University's football stadium, a ridge overlooks an expanse of rolling wheat fields where everything is solid green, as if painted over with a broad brush.

That's not how the Palouse Prairie naturally looks. It's the result of humans taking the land over and using the fertile ground for agriculture, stripping 99 percent of the prairie of its native plants.

But soon, researchers at Eastern Washington University hope to transform 120 acres of this land back into native prairie.

When they do, there will be clumps of yellow and pink flowers, bunch grasses of varying sizes, a diverse array of insects and wildlife drawn to their natural habitat. It will be the recipe used to try to restore a diverse ecosystem that's become endangered.

"This is our chance to be a part of that ecosystem and bring it back," says Erik Budsberg, EWU's sustainability coordinator and the project leader for EWU's Prairie Restoration project.

It will take years before the university-owned land will be restored, but the end goal won't just be a green space for students and faculty to escape to. It will be a "living laboratory," Budsberg says. The university will use it for research opportunities across a variety of disciplines, including biology and ecology.

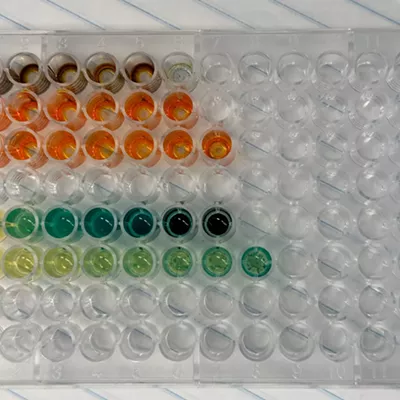

In fact, as the seeds of the first native plants begin to grow, it's already providing research opportunities for students. Kristy Snyder, a graduate student in the biology department, is studying the effects of planting annual seeds, trying to understand how they might help the ecosystem and why they're so scarce. She planted seeds on one and a half acres on the research site, and regularly tends the space to understand how the various plants are doing.

"It's really cool to be able to join in on the beginning of a project like this," Snyder says.

Justin Bastow, an assistant professor of biology at EWU, says there are several research questions that the restoration project could help answer. For example, how might the native plants affect soil critters and carbon sequestration in the soil? And how long does that recovery process take?

These are questions that students and faculty can study right there on campus.

"Those plants are going to support lots of bugs and bug diversity, which is what I'm really excited about — presumably also wildlife, birds, mammals and whatnot," Bastow says.

Other disciplines at EWU have benefited as well. Stacy Warren, the director of EWU's Geographic Information Systems, says computer science students have been able to help map out the land, in order to come up with an accurate digital representation. Archaeology students, meanwhile, have been out digging through the land to better understand its history. Geology students are using the land for research on groundwater.

"It brings students together from different disciplines and literally all walks of life," Warren says.

It will take several years or more before the land will look like its native habitat again. The plan was to plant seeds in fall 2020 for a 15-acre pilot site. But the pandemic delayed those plans. Right now, Snyder's acre and a half for her research is all they have for a pilot site. Budsberg hopes to plant more seeds this fall, when seasonal moisture should help the plants get established.

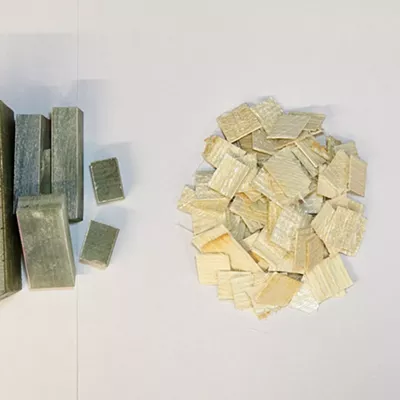

The other problem is that seeds for the native plant species can be expensive. The seeds for sticky geranium, a perennial plant with pink flowers, cost about $600 per pound, for example.

"It just costs orders of magnitude more than other species," says Becky Brown, EWU's biology department chair. "But it's really common in the Palouse. So if we really want to bring back the Palouse habitat, we need to get it established."

Alternatively, they could gather seeds from existing native habitat. But with only 1 percent of native prairie left, that's not always easy to do.

The project has been funded so far mostly through the EWU Foundation, and further funding may come from other individuals, companies or stakeholders that want to see the prairie restored.

Budsberg says the origin of the project began five years ago, when he and other university leaders started thinking about how to better use campus facilities. As sustainability coordinator, Budsberg was interested in reducing the carbon footprint and emissions of the university while also finding a way to sequester carbon. He started thinking about restoring the prairie, since it could also increase learning for faculty and staff.

"This is our chance to help have that large natural native green space on campus that really encourages folks to connect with our region more," Budsberg says. "The most important thing we can all do is have a better sense of place and understanding of how we can fit in our communities."

Restoring 120 acres won't put much of a dent in the overall landscape of the region. But by doing this work, the university believes it will be able to develop approaches to restoring the land that can help others if they choose to do the same.

Maybe, parts of the prairie will look like they used to, piece by piece.

"It's a model for students and the community for how this can look," says Brown. "I think more people will be inspired — its education and inspiration. I mean, that's what universities do." ♦